![]()

1

The Internal and External Failure of Accounting

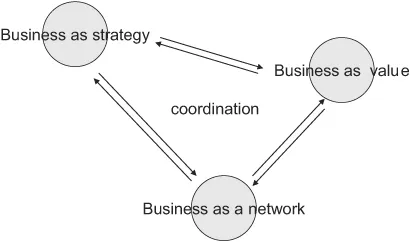

This book aims to provide a new understanding of accounting based upon an understanding of business that comes from the coordination of three different representations of business – business as strategy, business as a stakeholder network and business as value (Figure 1.1). The notion of understanding as being the coordination of different representative media comes from Hutchins’s (1995) work on distributed cognition. Commenting upon Hutchins’s work, Latour (1995: 4) supports the idea that cognition comes from the propagation and coordination of representations expressed through different media. He states

Cognition has nothing to do with minds or individuals but with the propagation of representations through various media which are co-ordinated by a very lightly equipped human subject working in a group, inside a culture, with many artefacts and who might have internalized some parts of the process. [underlining in the original]

The process of coordination of representations coming through various media is not neutral and in this case impacts upon each of the three representations of business. It is the impact upon the representation of business as (equity) value which generates the new accounting. Equity value is the value of the shareholders’ stake in the business.

To achieve coordination between strategy and the stakeholder network, strategy needs to be represented in terms of the stakeholder network. Hence strategy is described in terms of the leverage, engagement, alignment and development of the network, itself represented as a set of stakeholder propositions. In order to coordinate the stakeholder network with business value, the stakeholder propositions are in turn coordinated with equity represented by four funds (or slices) of equity value. The four slices of equity provide a new comprehensive balance sheet whilst movements within and between the four slices give the new comprehensive income. The evaluation of the business provided by the ‘new’ accounting does not sit outside the business model but is integral to it and leads to the reshaping of the stakeholder network and possibly the strategy itself. The point is that it is important for any business model to know how it will react to its own success or failure. Overall, the business model, being the articulation of how business is carried out, is represented by the mnemonic LEADERS. LEADERS stands for Leverage, Engage, Align, Develop (the strategic dimensions of the model), Evaluate (the accounting dimension of the model) and, on the basis of the evaluation, (Re) Shape the stakeholder network. For accounting to play its feedback role within this business model effectively, it must coordinate with both strategy and the stakeholder network.

Figure 1.1 Coordinating three representations of business

Much of this book is concerned with the internal failure of accounting. The internal failure of accounting is its failure to coordinate with (the rest of) the business model. Through coordination, accounting should not merely measure economic success; it should explain how that success (or failure) has been achieved and thereby identify the nature of the value created. Accounting should not stand outside the business but should be integral to the business and play a crucial role in its learning dynamics. To meet this challenge, the business model and the accounting model must be ‘co-developed’, a process that gives insights on both accounting and on business. The then incoming President of the English Institute of Chartered Accountants, Martin Hagen, was reported in Accountancy (Beattie 2009: 39) as being adamant that auditors are not to blame for the 2008 credit crisis. He is quoted as saying, ‘Let’s be clear – the reason there has been turmoil in the markets is that businesses had inappropriate business models for the circumstances’. But if inappropriate business models are not revealed by the reporting arrangements of which accounting and auditing are a central part, what is the use of financial reporting? We need an accounting which reveals any deficiencies in how business is carried out.

Coordinating with the Stakeholder Network

To understand the performance of the business we need to know not just how much value is created, but how value is created, who it is created for, what kind of value is created and how it is measured. We need an accounting model that covers each of these questions.

First of all business gets done and value is created through the capabilities of a network of stakeholders – customers, suppliers, employees, investors, government, management and of course the company itself which contributes capability in the form of fixed assets and intangibles such as patents. The company as a legal entity creates the network by contracting with other stakeholders but it is also a stakeholder in its own network. The idea that action takes place through networks of human and non-human actors is well established in the sociology of knowledge (see, for example, Callon 2008). Callon makes the point that actions (upon which business depends), such as piloting a plane or a shopper choosing between products in a supermarket, are possible because of distributed action and cognition around a network of ‘actors’. For business actions, knowledge is distributed around the stakeholder network and accessed through stakeholder relationships. This focus on access challenges traditional entity concepts for accounting based upon ownership and/or control. Control influences the risks attaching to access and ownership influences control, but access is the key intangible that in particular drives the new economy. The stakeholder network represents the distributed nature of modern business where knowledge/capability, reward, risk and value are all distributed.

WHO IS THE VALUE FOR?

The business creates value for all the stakeholders but if we are accounting to the company’s investors then they are primarily concerned with the value that the network creates for them as investors. Thus we should be accounting for the value of equity, rather than the value of the network or the value of the entity as a legal construct. Consequently, we need an accounting which analyses the movement in total equity value, taken to be market capitalisation, whilst relating this movement to the business model. It may indeed be possible to apply the concept of coordinating (strategic) direction, a stakeholder network and stakeholder values in other arenas such as the public sector and non-listed companies but these applications are not directly the focus of this book which is primarily concerned with accounting for equity in listed companies.

WHAT KIND OF VALUE?

The book introduces a six-dimensional stakeholder proposition in which the selection, engagement and alignment of stakeholders depends upon: (1) the specification of the product to be provided; (2) the price and volume; (3) the stakeholder knowledge and capabilities required (4) the nature of the relationship with the stakeholder; (5) the contractual promises made to the stakeholder; and (6) prospects for the entity and its business model (based upon non-contractual expectations). These are the six dimensions of the proposition that the company in effect makes to each stakeholder.

These dimensions are followed through to both returns and risk in order to identify how and where the network creates value. It is shown that equity value can reside in four distinct funds – the four slices of equity – being: (1) the traditional assets of tangibles and working capital; (2) intangibles; (3) promises; and (4) prospects.

HOW IS VALUE MEASURED?

Each of the four funds corresponds to both a different kind of value and a different kind of measurement. The ‘value’ of the traditional assets (net of loans) is taken to be the same as currently given in the reported financial statements. Intangibles are taken as the capitalised value of the current residual profit; residual profit being what is left after providing an appropriate return on the traditional assets. Thus the value of both traditional assets and intangibles is underpinned by the profitability of current production and together they form the ‘productive equity capital’. Promises, which can include pensions, warranties, deferred tax, derivatives and fixed price contracts, are taken at fair value net of any precautionary assets set aside. Prospects are valued as market capitalisation adjusted for the values of the other three funds and it is the credibility of this valuation which becomes the focus of attention for the investor. Promises and prospects both derive their value from expectations rather than current production and hence form the ‘speculative equity capital’.

Coordinating with Strategy

Currently accounting is most suited to an ‘old economy’ company in which strategy is designed to maximise returns on the traditional assets. However, the better option for many companies, particularly those primarily based in a developed (high cost, high technology) nation, is to compete for ideas in the new economy rather than to compete on cost and volume in the old. A ‘new economy’ business strategy is one which builds and exploits (leverages) the strengths of the stakeholder network, particularly those network intangibles connected with leading-edge knowledge and innovative propositions to customers and other stakeholders. Leverage in the new economy comes not only through increasing volumes but also increasing margins to reflect the leading-edge nature of the product. For services in the new economy the margin often flows from the ability to adapt the product to the specific needs of the customer. Investment in intangibles is higher risk and potentially higher reward than investment in fixed assets for the production of established products. Indeed a strategy to exploit intangibles drives the company into riskier business activities and consequently seeks to share or reposition the risks and rewards across the stakeholder network (Miller, Kurunmaki and O’Leary 2008). For this purpose, there may be risk and reward sharing agreements between the company and its suppliers, customers, employees, directors and financial institutions in addition to the traditional arrangements with shareholders. Moreover, risk and reward sharing is intended to help bind the stakeholder network together by engaging stakeholders and aligning them with the objectives of the company. The knowledge and capability of the stakeholder network leverages the capabilities of the company itself.

Risk and reward sharing agreements facilitate the implementation of any new economy business strategy. However, they are contractual promises and they leave a legacy for the future since the value of the contracts will move, at times unpredictably, as part of a changing environment and changing expectations. If not properly managed, this legacy itself can be a substantial source of risk for the company. The company should hold liquid ‘precautionary’ assets to cover this risk as well as ‘opportunity’ cash necessary to invest quickly in, and take early advantage of, any new ideas and knowledge ‘breakthroughs’.

It follows from this brief discussion of strategy that a new accounting should: (1) focus upon the performance and leverage of intangibles; (2) be responsive to the impact of risk in any strategy of leveraging intangibles; and (3) recognise separately the legacy value of promises made to reposition risk and reward around the network. There is a fourth requirement which is discussed in the next section: it is to distinguish the gains from productive activity and the gains from speculation.

Production and Speculation

Following the 2008 crisis, a lesson that should be learnt is the need to distinguish the results of production and speculation. Profits from ‘production’ occur when an activity produces outputs which are the subject of current consumption. The value of the outputs is matched with the corresponding inputs to give what might be termed phase one (productive) profit. The flow of future ‘phase one’ profits can be capitalised to give their capital value and this securitisation/monetisation gives rise to an increase in assets and ‘phase two’ profits. Subsequent changes in this capital value give ‘phase three’ profits. ‘Phase four’ profits come from commissions, fees and other charges that are associated with the initial capitalisation or with the management, trading or repackaging of existing capital. They are not associated with current production and are thus, like phase two and three, speculative. If speculative gains/profits lead to excessive salaries, bonuses, dividends and taxation which are spent on consumption, then, from a macroeconomic viewpoint, the economy becomes unbalanced insofar as there is no matching production. An economy is regarded as unbalanced when consumption runs ahead of production.

This book will argue that distributions, whether in the form of dividends, excessive salaries, bonuses or taxation, should be restricted to the yield on productive capital. Realised gains on speculative capital should be reinvested in productive capital and not distributed as these represent either wealth transfers or changed expectations as to the future and do not relate to current production. Distribution of speculative gains has been a particular problem in relation to financial institutions, notably banks. A bank’s productive capital exists in respect of banking activities when the activity, such as a business loan, is an input to a business conducting productive activity. Apart from this, most banking activity can be identified as speculative activity by the bank or its clients, or as lending to individuals to support consumption. Lending for consumption has played its part in unbalancing the economy and profits from this activity can be termed ‘phase five’. The problem is that when the economy needs more production and less consumption and speculation, rewarding on the basis of profits other than phase one profit motivates resources and talent toward non-productive activity.

An Unbalanced Economy

The macroeconomic indicators associated with an unbalanced economy (high on consumption and speculation, low on production) are well known and include excessive borrowing, an unconstrained financial sector, the sale of assets (notably infrastructure) to overseas buyers, unfunded and inadequately funded pension promises and, above all, persistent trading imbalances. The UK for instance has not had a significant trade surplus since the early 1980s and even then there was a substantial reliance upon North Sea oil and gas. Unlike say Kazakhstan, the UK did not create a sovereign wealth fund to try and sustain, albeit in a different form, the nation’s capital inherited in the form of natural resources. Conversely, there are other unbalanced economies which are low on consumption, high on production and with ‘excessive’ savings. Market mechanisms have either failed, or not been allowed, to deal with these imbalances. It is the imbalance between consumption and production which, colliding with financial innovation (Turner 2009), took us into the financial crisis of 2008 and it is these imbalances which make it difficult to grow out of the crisis. There is a popular view that deficit nations should go for growth and sort out the imbalances after the economy has been kick-started through stimulus policies. This, however, assumes that how to sort out the imbalances is understood. The problem is that for any already badly unbalanced economy with inadequate productive capability, supporting consumption through low interest rates or increased government spending tends to suck in imports and the economic imbalance between production and consumption is liable to continue or even deteriorate. Persistent trading imbalances will ultimately challenge the viability of globalisation and open markets. Stimulus should therefore be accompanied by incentives to rebalance the economy, and accounting has an important role to play here.

In particular, the accounting for banks and other financial institutions is crucial. It is argued that the banks should only be permitted to distribute gains from lending to businesses for productive investment and that all other gains, once realised, should not be distributed but should be invested in productive activity. It follows that banks need to report both the sources of profit (whether phase one, two, three, four or five) and the destination of realised gains. Arguably the financial reporting by banks does not currently do this with clarity. Consequently, the accounts of the banks provide little help for the management of the economy. Moreover, given that the fortunes of the banks and those of the economy are intimately linked, it seems reasonable to assert that the banks’ accounts provide little help either for those charged with governance of the banks. A one way accounting ‘valve’ in which speculative gains can be invested in production but not vice versa serves to meet the UK government’s concern that UK taxpayers should be insulated from the downside of speculative activity and the concern that banks are not sufficiently incentivised to support non-financial business.

The proximate cause of the 2008 financial crisis was irresponsible lending in the United States (US) housing market. Because the mortgages could not be repaid, capital was being lost but this was not recognised in good time by the accounting. This was a serious business failure and an accounting failure but, as has been argued, there is a deeper problem with accounting for financial activities than the timing of bad debts and impairments. The deeper issue is that much financial sector activity has the potential to imbalance the economy by converting capital in the form of speculative gains into consumption without, at present, this being recognised at all in the accounting for the financial institution. This is because the accounting for the financial institution is concerned with the maintenance of the institution’s financial capital and not with the maintenance of the productive economy as a whole. Speculative gains boost a financial institution’s financial capital but add nothing to the current production of the economy. And so the charge against accounting is that it reports the ‘capital into consumption’ activities of the financial sector as good news (increased profits and balance sheets) when in fact, from a wider perspective, it may not be. This charge uses the classic externality argument used to criticise accounting for its failure to recognise pollution from manufacturing, except this is the ‘pollution’ of the economy by the financial sector. The circumstances where the profits and balance sheets of the financial sector expand much faster than those of the productive sector that financial services are there to support is termed financialisation (see for example Elliott and Atkinson 2008: 17). With financialisation the financial sector absorbs...