Art, Literature and Religion in Early Modern Sussex

Culture and Conflict

- 286 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Art, Literature and Religion in Early Modern Sussex

Culture and Conflict

About This Book

Art, Literature and Religion in Early Modern Sussex is an interdisciplinary study of a county at the forefront of religious, political and artistic developments in early-modern England. Ranging from the schism of Reformation to the outbreak of Civil War, the volume brings together scholars from the fields of art history, religious and intellectual history and English literature to offer new perspectives on early-modern Sussex. Essays discuss a wide variety of topics: the coherence of a county divided between East and West and Catholic and Protestant; the art and literary collections of Chichester cathedral; communities of Catholic gentry; Protestant martyrdom; aristocratic education; writing, preaching and exile; local funerary monuments; and the progresses of Elizabeth I. Contributors include Michael Questier; Nigel Llewellyn; Caroline Adams; Karen Coke; and Andrew Foster. The collection concludes with an Afterword by Duncan Salkeld (University of Chichester). This volume extends work done in the 1960s and 70s on early-modern Sussex, drawing on new work on county and religious identities, and setting it into a broad national context. The result is a book that not only tells us much about Sussex, but which also has a great deal to offer all scholars working in the field of local and regional history, and religious change in England as a whole.

Frequently asked questions

Information

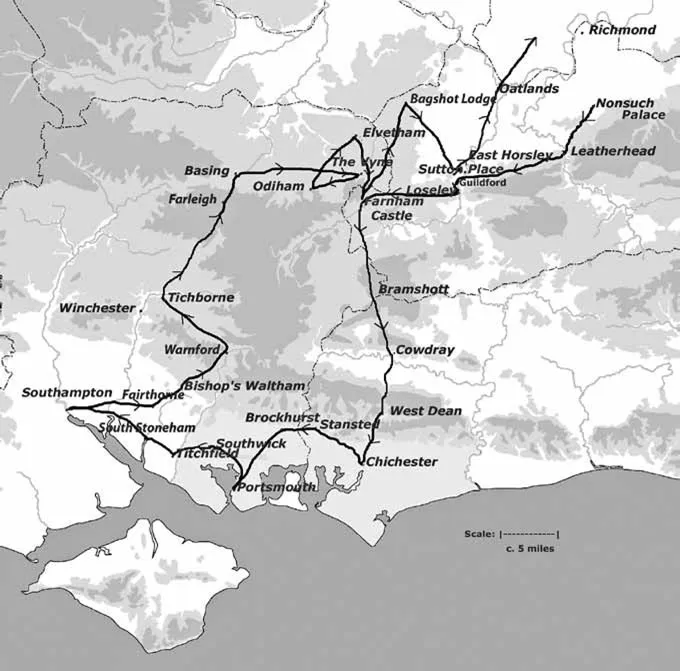

Chapter 1 Elizabeth I's Progresses into Sussex

The Route of the Progress of 1591 in West Sussex and Hampshire

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half-Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Figures

- List of Contributors

- Introduction: Contesting Early Modern Sussex

- 1 Elizabeth I’s Progresses into Sussex

- 2 Two Sussex Authors: Thomas Drant and Anthony Copley

- 3 Lambert Barnard, Bishop Shirborn’s ‘Paynter’

- 4 Intellectual Networks Associated with Chichester Cathedral, c. 1558–1700

- 5 ‘This strange conglomerate of books’, or ‘Hobbs’ Leviathan’: Bishop Henry King’s Library at Chichester Cathedral

- 6 ‘Your daughter, most devoted’: The Sententious Writings of Mary Arundel, Duchess of Norfolk, Given to the Twelfth Earl of Arundel

- 7 ‘The Government of this Church by Catholic Bishops hath always been a Strength and Defence unto the Kingdom’: Episcopacy and the Catholic Community in Early Seventeenth-century Sussex and Beyond

- 8 Richard Woodman, Sussex Protestantism and the Construction of Martyrdom

- 9 ‘The Happy Preserver of his Brother’s Posterity’: From Monumental Text to Sculptural Figure in Early Modern Sussex

- Afterword: Not the Last Word: Scraps of History

- Index