- 228 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Designing Sustainable Cities in the Developing World

About this book

Can conservation of the built heritage be reconciled with the speed of urban change in cities of the developing world? What are the tools of sustainable design and how can communities participate in the design of the environments in which they live and work? These are some of the questions explored within this innovative and richly illustrated book. A wealth of examples drawn from Mexico, Brazil, Indonesia, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, India and Myanmar demonstrate how rapid physical and social change has swept away historic urban quarters and the cultural heritage they represent. Written in an accessible style the rich mix of concepts, research methods, analysis and practice-based tools is designed for academics and professionals alike. Leading academics Zetter and Watson have produced a fascinating book that is amongst the first to explore the concept of urban sustainability within the context of urban design in the developing world.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Urban Form and Transformation

Chapter 2

Cultural Sustainability and Development: Drukpa and Burman Vernacular Architecture

Introduction

This chapter examines the relationship between a culture and its vernacular architecture by exploring the trends of continuity and change in two contrasting Buddhist communities – the Drukpa of Bhutan and the Burman of Burma/Myanmar. It considers in particular the contrasting affinities between secular and religious styles in these two traditions and shows how their vulnerability and differential response to exogenous forces of ‘development’ and ‘national’ identity generate both change and resilience.

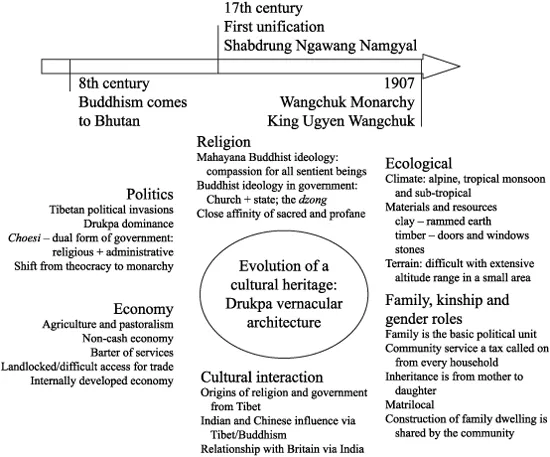

The common thread in the two case studies is the heritage of Buddhism which paradoxically has been the major proponent for change. It originated in India and came to Bhutan in the form of Mahayana Buddhism from Tibet during the eighth century. The links of Bhutan with Tibet would not be severed for another 12 centuries until Communist China’s invasion of Tibet. The influence of Tibetan culture extended from the religious, political, economical, and social spheres of Drukpa life. Similarly Theravada Buddhism reached Burma via Sri Lanka and defined the moral basis for its political framework and expansionist activities.

The British Colonial regime in India, the culture of colonisation and imperialism affected the economic, political, and social institutions of the Drukpas and the Burmans and had implications for cultural heritage and vernacular architecture. Both cultures reacted differently to western cultural influences.

Cultural Heritage, Development and Vernacular Architecture

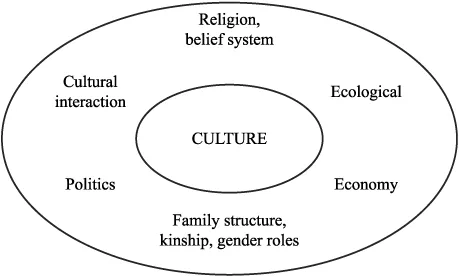

The cultural environment (Figure 2.1) comprises a variety of elements, each one affecting the evolution of the culture in varying degrees. Analysing the cultural environment is a method of understanding the complexity of a culture, its fragility, its resilience, and its reaction to change. If development as the proponent of change for a better life is truly concerned with the material and spiritual well being of people, this deeper understanding is essential. In this sense it would only be appropriate to define material and spiritual well being within the context of the culture.

Figure 2.1 The cultural environment

Cultural differences occur because cultural environments are unique and particular to a culture. Nation states often blur these differences amongst ethnic communities within territorially, politically and, at times, religiously defined limits. Perhaps it is with redefining the notion of nation as a community of diverse cultures, each one remaining autonomous for culture specific issues and united for national issues, that ‘global’ development policies can move towards. Development should be deferential to the culture.

Vernacular architecture is clearly a manifestation, a physical representation of the culture of a people. ‘Vernacular architecture’ comprises the dwellings and all other buildings of the people. Related to their environmental contexts and available resources, they are customarily owner or community-built, utilising traditional technologies. All forms of vernacular architecture are built to meet specific needs, accommodating values, economies and ways of living of the cultures that produce them (Oliver 1997). If vernacular architecture accommodates cultural needs we begin to realise the complexity involved in its evolution having to serve these needs and within the magnitude of social conditions to which it applies.

In Drukpa and Burman culture, religion, politics, economy, ecology and the social aspects (cultural interaction, family, kinship, and gender roles) have been the most relevant cultural components which give depth to the understanding of the cultural heritage and vernacular architecture. These cultural components have collectively been called the ‘cultural environment’, one which nurtured and formed the culture.

Evolution of Culture

Religion and Belief Systems

Buddhism was a unifying element that defined the states of Bhutan and Burma. Religion was the bond that held the Drukpas and the Burmans in unity. Their concepts of leadership and kingship evolved from religious doctrines. Society behaved and reacted towards this authority and moral order because of the common beliefs they held. They believed in the teachings of the Buddha as the way to freedom.

Theravada Buddhism adheres to the goal of being an arhant, to attain nirvana in the present life, never to be reborn again. Only ordained monks can achieve this status. Mahayana Buddhism deems the notion of the arhant as self-serving and instead encourages the adept to follow the Buddha’s own example in becoming a boddhisatva (enlightened being). Boddhisatvas delay the final entry into nirvana returning for several lifetimes to help others on the path to nirvana.

Contrasting religious influences are reflected in Drukpa and Burman vernacular architecture. The closer affinity between ecclesiastic and secular architecture of the Drukpas than that of the Burmans is a reflection of these differences in religious interpretation. The Drukpas of the Mahayana Buddhist school encourage the sharing of the doctrine so all sentient beings may attain nirvana. This sharing of monastic building traditions with vernacular dwellings is also practiced in the close relationship between the monastic and secular community. The marked distinction between Burman ecclesiastic architecture and the vernacular dwellings reflects the elevated status that members of the monastic community have for their special access to the doctrines leading to enlightenment.

Economy

In defining economy one considers the wealth and resources of the society in terms of the production and consumption of goods and services. Economy is the way of life beginning from immediate needs for sustenance, food and shelter, to the regional market exchange of goods, to global trade and its effect on the culture. The community’s way of life, whether it be agriculture, pastoralism or trade has bearing on the house form, orientation, location, decoration, building materials and building process.

Drukpa and Burman society evolved from being predominantly agricultural through periods of regional trade, isolation, and global recognition. The economy brought changes in social stratification. Whereas the Burmans controlled this distinction with sumptuary laws, the Drukpas reacted differently. A rural peasant community, the Drukpas never had a powerful aristocracy and the transfer of building technology, art, and culture between the religious and the secular was less restricted.

Burman sumptuary laws produced a marked distinction between the architecture of the religious and the ruling elite and that of the commoners. This sumptuary distinction is not as defined with the Drukpa architecture because of the absence of strong social stratification.

Positive trends in the economy resulted in a surplus of wealth. This excess wealth went into the support of the sangha, the Buddhist religious order of ordained members. For Buddhists, status is defined by generosity and how much one can contribute to the cause of religion. It was through royal patronage, community donations, and corvée labour (taxation in the form of labour) that vernacular architecture in the form of stupas, zedis, monasteries, dzongs (Bhutan’s fortress-monastery) were built.

Politics

The Drukpas and the Burmans were first a socio-cultural-ethnic unity before they were a political organisation described as kingdoms. As their territory expanded, their influence and authority extended to other ethnic groups who accepted their hegemony and their cultural values. Both cultures emerged as the dominant ethnic group, which defined cultural identity when it became necessary to have a national culture. This in itself has caused problems in the form of ethnic division within each nation as cultural differences arose within various ethnic groups. The acceptance of Drukpa cultural heritage was less resisted within the predominantly Buddhist kingdom. The harmonious architectural landscape lends itself to this Drukpa cultural dominance. It is not without problems for the non-Buddhist Hindu communities of southern Bhutan, which still seek to find a solution for integrating into this culture.

Political institutions were formed, selected and supported by the society. For the Drukpas and the Burmans, the monarchy and Buddhism were key elements, which defined the political institutions prior to 1900. Changing fortunes in politics had a bearing on architectural form for both cultures, evident in the form of the dzongs of the Drukpas, the sumptuous monasteries of the Burmans which were royally endowed, the gold leafed zedis or stupas, and the lakhangs or temples of Bhutan which undergo cyclical construction and deconstruction.

Political institutions were instruments for social control: order symbolising social solidarity. For Bhutan political institutions became venues for the spread of the Drukpa Kagyupa line of Buddhism and consequently Buddhist inspired architecture subservient to maintaining political dominance. The Burman monarchy royally endowed the sangha, which became a powerful instrument for maintaining social order. Consequently the Buddhist concept of kingship and public welfare defined the code of conduct and duties of the monarch. The emerging cultural dominance of the Drukpas and the Burmans was not always a peaceful process despite the aversion of Buddhism for violence.

Family, Kinship and Gender Roles

The relationship of the lineage principle which takes into account marriage patterns, inheritance, land ownership, political organisation and social status is clearly illustrated when the Drukpa dwelling is passed on from mother to daughter. The cyclical rebuilding of the family dwelling every 20–25 years, when the eldest daughter marries and assumes the position as head of household, is a community tradition. The mutual help system keeps the community tightly bound. Men have access to a monastic life and the intellectual study of Buddhist doctrines. Because of matrilocal traditions in Bhutan, men move to villages beyond their place of birth to live in their wives’ household. Systems of family, kinship and gender roles are different for each community and are therefore reflected in their dwellings and other forms of vernacular architecture.

Cultural Interaction

As the introduction has noted, the heritage of Buddhism and the British Colonial regime have been the major proponent for change. Over more than 12 centuries Buddhism has exerted a profound influence on religious, political, economical, and social spheres. More recently, British colonisation and imperialism has similarly impacted the economic, political, and social institutions. This has had significant implications for the cultural heritage and vernacular architecture, although with different outcomes for the Drupka and Burman societies.

Ecological Environment

Geographic location, natural resources, and climatic conditions have a direct bearing on the manner in which homes are built, and the construction materials made available by the environment. The ecological environment dictates the source of livelihood and consequently the house forms are defined by these elements.

The Drukpas of Bhutan

To the Bhutanese, their country is known as Drukyul, land of the Drukpa sect. The dominance of the Drukpa Kagyupa sect of Tantric Buddhism has given it this name. In 1907, the weakening Buddhist theocracy transferred its political powers to a hereditary monarch. Ugyen Wangchuk’s skills of diplomacy permitted the flourishing of local Bhutanese multi-cultures in a relatively peaceful albeit more isolated environment, which was not subservient to a colonial power.

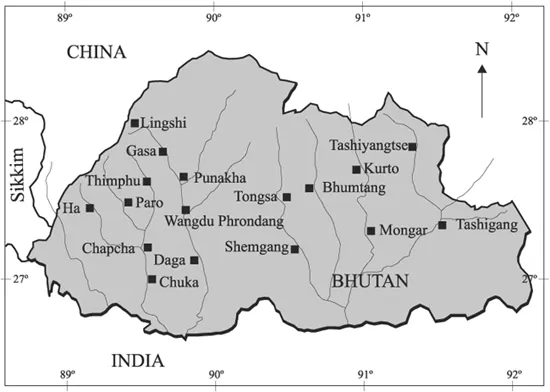

Bhutan is a landlocked country whose geographic location set limits for its contact with much of the outside world (Figure 2.2).

The Drukpas occupied the central zone with a temperate monsoon climate (Figure 2.3). Their settlements along the western and central valleys clearly reflect their Buddhist background. They maintain multi-crop farms and keep animals. The difficult terrain has kept the different valleys largely economically independent particularly in food production. Other valleys are inhabited by other ethnic groups but it is Drukpa culture that dominates when defining the national language, dress, religion, and architecture.

Figure 2.2 Location map of Bhutan

Figure 2.3 Settlements along the central zone of Bhutan

Figure 2.4 Evolution of the cultural heritage and its influence on Drukpa vernacular architecture

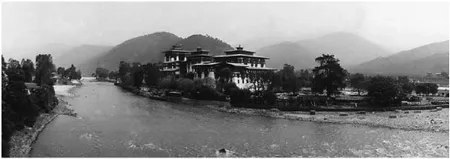

Dzongs as Centres of Culture

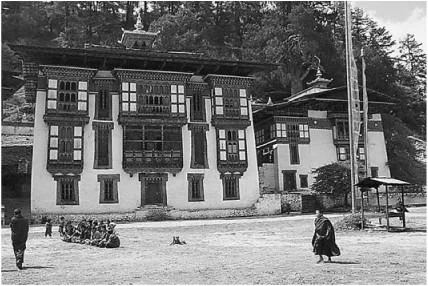

The dzongs in each valley symbolised the might of the Drukpa School with each one containing a monastery and an administrative centre (see Figure 2.5). There were 16 historical dzongs built in Bhutan during and shortly after the reign of the Shabdrung Ngawang Namgyal (1594–1691). The Shabdrung was the first religious-political leader that unified Bhutan. As a governmental institution, the dzong can be considered the socio-political heart of a dzongkhag (valley community). Personal and public affairs centred on the dzong, familiarity with the architecture influenced building traditions of the farmhouses. Dzong architecture with its embodiment of Buddhist values acted as a cultural magnet and a source of inspiration; it became the trendsetter for Bhutanese architecture. As Dujardin observes, ‘In Bhutan, religion is the mediating factor that unites and integrates all aspects of culture into a distinct whole, crystallised in material culture’ (Dujardin 1994: 152). Other monastic buildings which dot the countryside and remain in harmony with Buddhist inspired architecture include lakhangs (temples) (see Figures 2.6 and 2.7), gompas (monasteries), chörtens (stupas), mani (prayer walls), and the lukhang and tsenkhang (spirit houses).

Figure 2.5 Punakha Dzong, 19991

Visual evidence from 1783 and recent photographs show the resilience of dzong architectural tradition (see Figure 2.8). However, none of the dzongs have remained exactly as they were built, because the concept of historic restoration in the Bhutanese sense is not one of maintaining buildings as they were but of buildings going through a continuous process of renovation depending on current needs. This process remains deeply rooted in Buddhist ideals, particularly that of impermanence. To a Buddhist, nothing is considered permanent in the unending cycle of life and death. The intrinsic form of each dzong may remain the same, as they were strategically planned for the specific terrain, but detailed changes and improvements are implemented with each renovation. The same process of construction and deconstruction apply to other monastic buildings and vernacular dwellings.

Figure 2.6 Kurjey Lakhang with the special roof lantern allowed only for palaces, temples and monasteries, 1999

Figure 2.7 Annual m...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- List of Acronyms

- List of Contributors

- INTRODUCTION

- Part I: Urban Form and Transformation

- Part II: Designing People-based Environments

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Designing Sustainable Cities in the Developing World by Georgia Butina Watson, Roger Zetter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & City Planning & Urban Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.