Educational borrowing is not a modern-day phenomenon. For example, cross-cultural exchanges between China and other regions started as early as the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) with the introduction of Indian Buddhism into China (Zhang and Wang, 1997, cited in Bray and Qin, 2001). This chapter provides the theoretical framework for our study on China by discussing the key concepts, theories and models of educational policy borrowing. The first part introduces the concept of educational borrowing in an era of globalisation. This is followed by a discussion of the four stages of policy borrowing in education, as well as other theories and models of educational borrowing. The last section elucidates the concepts of culture, cultural scripts and indigenisation, as well as their influences on educational borrowing.

The concept of educational policy borrowing in an era of globalisation

Following Phillips and Ochs (2004a), ‘educational policy borrowing’ refers to ‘the conscious adoption in one context of policy observed in another’ (p. 774) and a ‘clearly enunciated intention to adopt a way of doing things observed elsewhere’ (p. 776). It covers ‘the whole range of issues relating to how the foreign example is used by policy makers at all stages of the processes of initiating and implementing educational change’ (Phillips and Ochs 2003, p. 451). Policy borrowing is ‘a deliberate, purposive phenomenon in educational policy development’ (Phillips, 2009, p. 1061). Policy borrowing takes place within a continuum of educational transfer, from imposed educational transfer at one end to voluntary adoption of foreign examples, models and discourses at the other (Phillips and Ochs, 2004a, 2004b; Steiner-Khamsi, 2000). The term ‘borrowing’ is used synonymously in this book with terms such as ‘transfer’, ‘copying’, ‘appropriation’, ‘learning’, ‘importation’ and ‘cross-national attraction’.

Globalisation has catalysed the interest in, and pace of, educational borrowing across nations. Policymakers worldwide have acknowledged that the ability of their countries to compete in the globalised knowledge economy is increasingly dependent upon their capacity to meet the fast-growing demands for high-level skills. This in turn hinges on how countries are making significant progress in improving the quality of education of their people and providing equitable learning opportunities for all (OECD, 1996; McKinsey and Co, 2007, 2010; Tan, 2010). Not just an external force, globalisation is also a ‘domestically induced rhetoric’ that reflects the context-specific reasons for receptiveness of the borrowed policy (Steiner-Khamsi, 2014, p. 157). Consequently, the ‘globalisation thesis’ has been used to ‘explain almost anything and everything, and is ubiquitous in current policy documents and policy analysis’ (Ball, 1998, p. 123; see also Ball, 1994). Terms such as ‘innovation’, ‘problem-solving’, ‘inquiry’, ‘autonomy’ and ‘cooperation’ – championed in China’s current education reform, as I shall explain later – are part of international discourses that appear to exist without structural roots or social locations, or what Antonio Nóvoa terms ‘planet-speak’ (as cited in Takayama, 2009, p. 127).

Further sustaining and driving the phenomenon of educational borrowing is the impact of national assessment and international testing on policymaking (Kamens and McNeely, 2010). The trend for policymakers to introduce educational changes based on their students’ performance in such tests and assessments has given rise to ‘policy mechanics’: the identification of specific practices that contribute to student achievement elsewhere (Fuller and Clarke, 1994). The focus is on education policies and practices that are perceived to have worked elsewhere, especially in ‘reference societies’ (Schriewer and Martinez, 2004). Although it is difficult to identify clearly today the country of origin of ‘well-travelled’ reforms such as student-centred learning and parental choice of schools, there is no doubt that these reforms ‘were more often than not initiated in the global North and then funded for dissemination to the rest of the world’ (Steiner-Khamsi, 2014, p. 160). Unsurprisingly, many developing countries are increasingly looking to the global North – or, in the context of this book, looking West – to improve, transform and modernise their educational systems.

Nóvoa and Yariv-Mashal (2003) point out a paradox that exists when nations use global benchmarks for local agendas:

It is important to acknowledge this paradox: the attention to global benchmarks and indicators serves to promote national policies in a field (education), that is imagined as a place where national sovereignty can still be exercised. It is not so much the question of cross-national comparisons, but the creation and ongoing re-creations of ‘global signifiers’ based on international competition and assessments.

(Nóvoa and Yariv-Mashal, 2003, pp. 425–426, emphasis in the original)

A significant point about Nóvoa and Yariv-Mashal’s observation is that ‘global signifiers’ or ‘sliding signifiers’ (Takayama, 2009) are being re-created in an on-going fashion. Reform initiatives such as ‘student-centred’ teaching is being re-interpreted and re-imagined in such a way that the final form it takes in a locality may be very different from that in the original setting. There is therefore a need to analyse how global signifiers, when borrowed and transplanted into a new locality, take on varied connotations and produce new assemblages, connections and meanings.

The four stages of policy borrowing in education

Different writers have highlighted various aspects of educational borrowing, such as the four stages of the policy borrowing process (Phillips and Ochs 2003), the theory of policy attraction (Phillips, 2004), outcomes-based education (Steiner-Khamsi, 2006; Steiner-Khamsi, Silova and Johnson, 2006; Steiner-Khamsi and Stolpe, 2006) and the politics of policy borrowing and lending (Steiner-Khamsi, 2002, 2004a, 2004b). This section focuses on Phillips and Ochs’ (2003, 2004a) four stages of policy borrowing in education, which was based on their analysis of British interest in educational provision in Germany. I have chosen to focus on this model as it is an influential ‘Oxford model’ (Rappleye, 2006) that serves as a potential analytical tool to examine educational borrowing, especially in non-Western contexts. This point was noted by Phillips and Ochs (2004a) themselves who expressed the hope that their model could be applied to other cases of policy transfer. Pointing out that the model was ‘preliminary’, they added that ‘it will inevitably change as a result of future attempts to apply it to instances of policy borrowing in various contexts’ (p. 781). They elaborated:

We need now to extend the range and investigate the attention paid in Britain to other countries and we hope that others will report on the usefulness of the model in other contexts of policy borrowing around the world. To that extent we hope that the model will serve as a helpful analytical tool which can undergo further development as it is tested by means of many examples.

(Phillips and Ochs, 2004a, pp. 782–783)

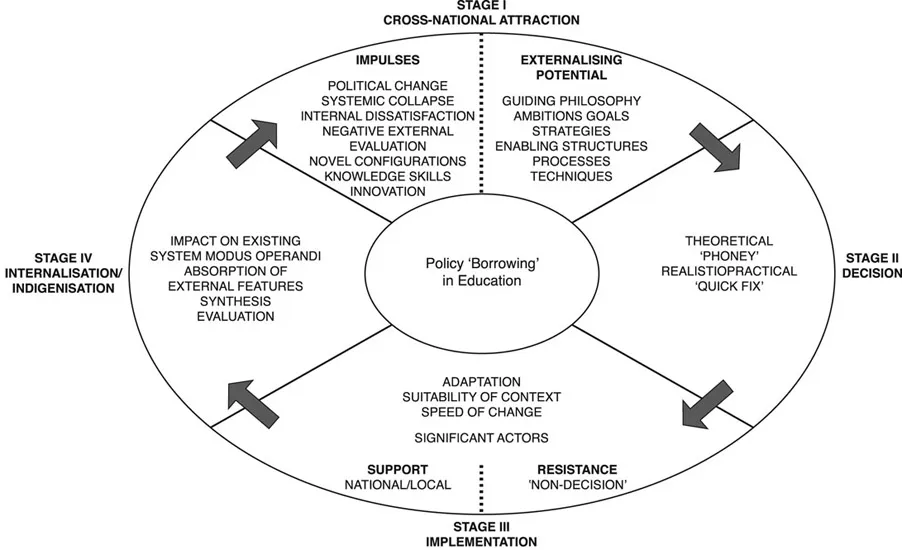

I shall briefly outline the four stages, the content of which is taken from Phillips and Ochs (2003), unless otherwise stated. I will include the theories and models of other scholars as and when such a discussion is relevant to our understanding of Phillips and Ochs’ model. The four stages are cross-national attraction, decision, implementation, and internalisation/indigenisation (see Figure 1.1).1

The first stage, cross-national attraction, is comprised of two parts, namely ‘impulses’ and ‘externalising potential’. The former refers to the preconditions and motives for borrowing. These include both internal factors such as political change (e.g., a change of regime) and dissatisfaction of key educational stakeholders (parents, teachers and students, etc.) with the local education system, as well as external factors such as unsatisfactory external evaluation in international assessments (e.g., the Programme in International Student Assessment (PISA)) and economic competition (e.g., global emphasis on nurturing graduates with twenty-first century competencies).

Different stakeholders may have different and even conflicting motives and motivations for attraction and borrowing. Ochs (2005) outlines four main motivations for educational borrowing as follows (pp. 20, 68–69 as cited in Rappleye, 2007, pp. 20–21):

- To caution against educational reform.

- To glorify current education at home in comparison with other nations (Steiner-Khamsi, 2004b).

Figure 1.1 Phillips and Ochs’ four stages of policy borrowing in education

- 3 To legitimate the adoption of reform of educational policy at home (Gonon, 1998; Nóvoa and Yariv-Mashal, 2003; Steiner-Khamsi, 2004b; Halpin and Troyna, 1995).

- 4 To scandalise policy and practices at home, substantiating and validating the need for reform (Steiner-Khamsi, 2004b).

It is important to note that there may be more than one motivation at work when educational stakeholders debate over whether a model or policy from elsewhere should be borrowed. As Phillips (2009) has noted, the example of reform in Sweden was seen as being ‘exemplary both ways’: glorified by supporters and scandalised by detractors concurrently. Furthermore, it is possible for the same stakeholder to scandalise, legitimise, caution and glorify the same or different policies at the same or different time(s). There are therefore multiple possible permutations involving the three variables: stakeholder, policy and time. The exact (re)actions of the stakeholders would depend on the specific context, issue or problem concerned, needs, interests and agendas of the parties involved, as well as other contingent factors.

Even when the stakeholders share the same motivation for a particular policy, they do not necessarily interpret the policy in the same way or share the same goals. In fact, the contrary may be true, as pointed out by Rappleye (2006, p. 234):

This type of attraction-cum-borrowing links to work in other disciplines – what anthropologists have termed ‘multivocal symbols’ (Turner, 1974) and what sociologists call (p. 233) ‘keywords’ (Williams, 1983) – permitting different groups to ‘agree while actually holding different understandings and pursuing different agendas’ (Goodman, 2003, p. 15).

The process of educational borrowing reminds us that policies are both ‘systems of values’ and ‘symbolic systems’ (Ball, 1998): not only do they represent and account for political decisions and seek to achieve material effects (as systems of values), they also serve to legitimise political decisions and garner support for the material effects intended by the policymakers (as symbolic systems). Far from being well planned, neat and logical, national policy making is what Ball (1998) calls ‘a process of bricolage’:

National policy making is inevitably a process of bricolage: a matter of borrowing and copying bits and pieces of ideas from elsewhere, drawing upon and amending locally tried and tested approaches, cannibalising theories, research, trends and fashions and not infrequently flailing around for anything at all that looks as though it might work. Most policies are ramshackle, compromise, hit and miss affairs, that are reworked, tinkered with, nuanced and inflected through complex processes of influence, text production, dissemination and, ultimately, re-creation in contexts of practice.

(Ball, 1998, p. 126)

It is especially pertinent to highlight, among the motivations for educational borrowing, that of scandalising. This motivation is similar to what Phillips (2000) calls ‘distortion’ or ‘exaggeration’ – the strategy used by policymakers to exaggerate, whether intentional or otherwise, evidence from overseas with the purpose of highlighting perceived deficiencies at home. It brings to our attention the concept and practice of externalisation (Schriewer, 1990). As explained by Steiner-Khamsi (2006, pp. 670–671):

According to this theory, references to other education systems function as leverage to carry out reforms that otherwise would be contested. Schriewer and Martinez (2004) also find it indicative of the (p. 670) ‘socio-logic’ of a system that only specific education systems are used as external sources of authority. Which systems are used as ‘reference societies’ (Schriewer and Martinez, 2004, p. 42) and which are not, tells us something about the interrelations of actors within various world-systems.

Externalisation centres on how the policymakers turn to ‘international standards in education’ to obtain a ‘certification effect on domestic policy talk’ and generating reform on domestic developments (Steiner-Khamsi, 2009, p. 1155). Complementing the concept of externalisation is Willis and Rappleye’s (2011) idea of advocacy comparison, which is ‘a vision of education that continues to imagine the Other as simply a tool of legitimation, leverage and authority for domestic reform debates’ (p. 21). Such a strategy, in my view, is a form of externalisation as the advocator relies on an external source, in this case, ‘the Other’, to generate changes in domestic developments. However, what is instructive about advocacy comparison is its emphasis on ‘othering’ that tells us more about the person who does the imagining than the ‘Other’ who is being imagined. The externalisation thesis highlights the ‘politics of policy borrowing’ (Steiner-Khamsi, 2004b), where the focus is not so much on the nature of the borrowed policy but on the political agendas and conflicts behind the borrowing in the local context (Steiner-Khamsi, 2006). To that, I would add that the concept of externalisation also foregrounds the culture of policy borrowing where indigenous beliefs, values and assumptions directly shape the local stakeholders’ interpretations and appropriation of a borrowed idea or practice. I shall return to this topic of culture at a later section in this chapter.

Besides ‘impulses’, the other component of cross-national attraction is ‘externalising potential’. According to Phillips and Ochs, this refers to aspects of educational policies and practices that can be borrowed. In another article, Ochs and Phillips (2002) classify the externalising potential under ‘six foci of attraction’:

- guiding philosophy or ideology of the policy;

- ambitions/goals of the policy;

- strategies for policy implementation;

- enabling structures that support education and the education system;

- educational processes (style of teaching and regulatory processes); and

- educational techniques (ways in which instruction takes place).

Ochs and Phillips (2002) observe that educational borrowing can occur at any focus of attraction. They explain, ‘a foreign country may be interested in only the techniques described in an educational policy, a combination of elements, or the whole policy’ (p. 330). These foci are situated within 13 elements of context – demographic, geographical, historical, political, social, cultural, religious, linguistic, philosophical, administrative, economic, technological and national character – by which they are shaped and which in turn shape the extent of adaptability for the focus of attraction. In other words, these elements of context undergird and influence the stakeholders’ perceptions of, and motivations in, borrowing and (re)actions towards foreign ideas and practices.

The second stage, decision, comprises the range of measures taken by the government and other agencies to launch the process of change. Phillips and Ochs identify four descriptors that illustrate the decision (Phillips and Ochs, 2004a, p. 780):

- Theoretical: broad policies that might remain general ambitions not easily susceptible to demonstrably effective implementation.

- ‘Phoney’: enthusiasm shown by politicians for aspects of education in other countries for immediate political effect, without the possibility of serious follow-through.

- Realistic/practical: measures which have clearly proved successful in a particular location without their being the essential product of a variety of contextual factors, which would make them not susceptible to introduction elsewhere.

- ‘Quick fix’: a dangerous form of decision-making in terms of the use of foreign models as easy solutions for the time being.

The third stage is implementation, where a foreign model is adapted based on the contextual factors of the borrower system. Phillips and Ochs aver, ‘Careful examination of the context in both the “home” and “target” countries is essential to evaluate compatibility and comparability and so to determine what is possible to borrow, given different cultural mores, demographics, etc.’ (2004a, p. 458). The extent of change depends on the adaptability of the spec...