![]() PART I

PART I

Theory![]()

Chapter 1

Forms of Rule in the Post-Soviet Space: Hybrid Regimes

Timm Beichelt

Does it make sense to classify political regimes as ‘hybrid’ and, if yes, what are the properties and consequences of such a classification? In order to answer this question, we try to map the field of conceptual and empirical research which concentrates on the phenomenon of political regimes that are neither clear democracies nor outright autocracies. Specifically, the potential need for a hybrid type arises when real world cases unify elements belonging to different established regime types, for example the simultaneous existence of pluralist elections (a feature of democracies) and media repression (a feature of autocracies). The term hybridity in that sense can simply be associated with a ‘mixture’ of components which – according to a given theory – belong to two or more different categories.

One of the major debates concerning hybrid regimes has addressed the issue of whether the establishment of hybrid types should be seen as an element of scientific progress or as an indicator of insufficient classification. On the one hand, the creative development of a genuine regime type may be able to describe regime characteristics more adequately and to capture specific properties of power relations or other political variables. On the other, an explicit dissociation from established categories like ‘democracy’ or ‘autocracy’ goes along with an abdication of understanding with regard to typical power constellations and their consequences. Any construction of new types therefore faces the fundamental challenge to make us better understand our phenomenon, which can already partially – but not completely – be understood. Introducing the category of a hybrid regime to systematic regime studies is only justified if that category is better able to describe or explain features of political power that remain poorly grasped as elements of either democracies or autocracies.

The hybridity of regimes started to be identified as an object of research during the mid-1990s. As such, it constitutes an issue of studies on the Third Wave of transition (after Huntington 1991). In the early years of the Third Wave, the problem was not in the centre of scholarly attention. Rather, both political actors and scholars acted on the assumption of two dominant pathways – democratic stabilization and consolidation (Diamond et al. 1997) on the one hand or democratic breakdown (Linz 1978) on the other. Only after some time did certain countries obviously deviate from these diametrically opposed expectations by remaining in the status of incomplete transition over a longer period of time. The debate on the character of hybrid regimes gained special momentum because important cases of transition studies – for example, Argentina, Indonesia, and Russia – were or still are involved.

The chapter proceeds as follows. In the second section, we try to identify how hybrid types are constructed. This section will demonstrate that hybrid types are sometimes seen as genuinely distinct from other types. At the same time, however, hybridity is associated with the creation of subtypes, for example with different sub-forms of democracy or autocracy which deviate from the allegedly ‘complete’ types. The third section enquires into this finding by more closely discussing these different logics of construction. On the one hand, a phenomenon-specific approach has brought forward types without clear associations to democracy and/or autocracy; we will call them ‘oscillation regimes’. On the other hand, the creation of subtypes leads to two sorts of sub-regimes: incomplete democracies and incomplete autocracies. In the literature, we find different suggestions for their classification, which will be briefly discussed. The fourth section will take a look at empirical developments, and the fifth section will summarize the results.

Hybrid regimes: Core Principles

From a bird’s eye perspective, two diverse strategies of coping with the difficulties of shabby typologies have been adopted in the transition literature (Krennerich 2002: 59-61). The first strategy consists in the mixture of regime elements in order to define new regime types. This is where the term ‘hybridity’ was used most prominently (Karl 1995). Terry Karl used it for Central American cases in which democratic elements – here: pluralist political competition – and non-democratic features – here: clientelist decision-making procedures – existed alongside each other. The second strategy does not mix regime type elements but creates special occurrences of established regime types. One of the most prominent expressions of transition studies is ‘democracies with adjectives’ (Collier and Levitsky 1997): democracies which lack one or another element of theoretically consolidated democracies. More recently, authoritarian regime types with additional attributes have also been discussed (Levitsky and Way 2002, Shevtsova 2004).

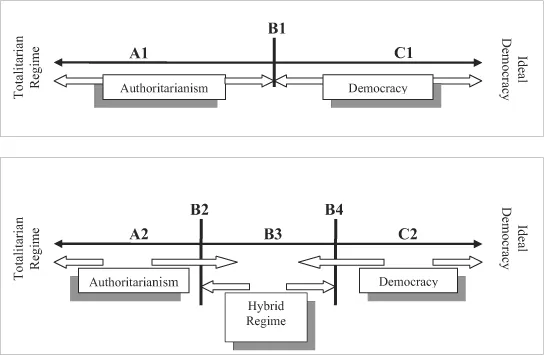

In Figure 1.1, the constitutive logics of these different strategies of type construction are visualized. The first variant may be called a ‘pure type’ strategy. Authoritarianism (A1) and Democracy (C1) are separated by a clear line; in that sense every political regime belongs to either one or the other type. In a strict sense, the term hybridity should therefore even be avoided; there is no room for deviating types. From a purely logical point of view, one would always have to speak of main types or main type alienation from that perspective. Still, many authors use the term ‘hybridity’ when cases, usually countries, are supposedly located on or close to the dividing line B1. The logic is tellingly sketched by Wolfgang Merkel’s term of a ‘defective democracy’ – a democracy with certain shortcomings which (if we follow Merkel) still allow the usage of the dominant concept ‘democracy’ (Merkel 2004).

Figure 1.1 Pure Types Versus Fuzzy Types

Source: Compiled by the author.

The second variant, also visualized in the figure, leaves a deliberate gap between democracy and authoritarianism.1 Hybridity is not limited to a crossover region but comes in three variants: B3 indicates the core of the genuine type; B2 and B4 present regimes which are on the edges of the regular types A2 and C2. In principle, the regimes on and around B2 and B4 could also be defined as ‘incomplete’ with regard to the established types. In practice, however, scholars rather tend to focus on B3 as the newly created type and try to include various features in it. Therefore, hybrid types always bear elements which are – in other conceptions – attributed to either democracies or autocracies. Examples are elections, the rule of law, and the freedoms of speech and assembly on the one hand, and electoral fraud, fragile judicial systems, and tutelary rulers on the other.

The examples remind us of the fact that all political regimes are composed of various elements rather than being centred around one decisive structural feature. To be sure, some existing regime typologies are one-dimensional. The prime example that comes to mind concerns elections, which have been declared central to democracy in certain democratic theories (Schumpeter 1976 [1942], Downs 1957). These minimalist conceptions, however, are inadequate for an advanced analysis of post-transition democracy – if cases are not clear, the whole problem consists in hard-to-capture interactions beyond elections. Therefore, the white arrows in the lower figure indicate that hybrid regimes always bear characteristics of both democracy and authoritarianism.

If this finding is accepted, another question arises: Can certain patterns of mixture between ‘democratic’ and ‘autocratic’ elements be discerned? A first answer has again to allude to the main types. In fact, there are no conceptions of democracy that are ready to disclaim elections as the core element of democracy. Many theories insist that there must be more to a democracy than just free and fair elections (Held 1996). Democracies without non-manipulated elections, however, are not possible. Therefore, no compromises concerning hybridity can be made in connection with elections. With regard to that variable, all regimes are indeed either democratic or non-democratic (Merkel 2004).

Logically, hybrid regimes therefore consist of free elections as well as other regime elements which introduce a partially autocratic character.2 Usually, it has been argued that these have to do with the specific understanding of incumbents of allowing possibilities of democratic control. The clientelism discussed by Terry Karl questions the autonomous formation of elite structures, leading to decision networks beyond public control (Karl 1995). Friedbert Rüb locates hybridity in the lack of willingness of democratically elected incumbents to limit the extent of their own power (Rüb 2002). More specifically, Rüb associates hybridity with a typical combination of a) democratic power legitimation and power exercise and b) autocratic power structures and an unlimited reach of incumbent power.

If we follow his concept, hybrid regimes are characterized by pluralism, free and fair elections, and at least some rule-of-law elements. Furthermore, the structure of power is ill-defined due to weak horizontal control, leading to a barely controlled executive which is itself able to decide how to limit its own power (Rüb 2002: 106). This highlights the long-discussed affinity between regimes with strong presidents and autocratic characteristics (Linz 1990). However, Rüb addresses this relationship in more abstract terms by speaking of control powers within a regime of checks and balances, rather than focusing on strong presidents alone (Rüb 2001).

In sum then, hybridity can be associated with two sorts of political regimes. Pure types refer to the ‘main types’ of democracy and authoritarianism and add additional attributes. Prominent examples, just to name a few, are Kubicek’s ‘delegative democracy’ (Kubicek 1994) and ‘competitive authoritarianism’ as designed by Levitsky and Way (2002). The other variant is characterized by fuzziness. Democratic and non-democratic elements coexist, stand in complex relations one to another, and form regimes with distinct characteristics.

Alternative Concepts: Diminished Subtypes, Oscillation Regimes

What are the properties of hybrid regimes according to the two typological principles discussed in the previous section? My argument is that pertinent types of hybridity are based on essentially different strategies of type construction, namely the development of diminished subtypes in the pure-type dimension and of oscillation regimes in the fuzzy-type dimension.

The pure-type strategy results in the creation of subtypes of either democracy or authoritarianism. It follows the approach of Collier and Levitsky, who define (in their case: democratic) regimes as categories with a set of distinctive features (Collier and Levitsky 1997). Subtypes of these main types are ‘diminished’ in the sense that they are incomplete, or ‘defective’, with regard to the main type. For example, ‘delegative’ democracies are inferior to consolidated democracies because of their weakness with regard to the horizontal control of powers (Kubicek 1994, Merkel et al. 2003: 87-91). An alternative to the creation of diminished subtypes would be the establishment of differentiated subtypes, as is, for example, the case with presidential or parliamentary democracy. These do not alter the character of the respective main type. Diminished subtypes do so by adding attributes which do not belong to the defining elements of the main type (Krennerich 2002: 60-61).

The most systematic approach to capture diminished subtypes of democracy has been developed by Wolfgang Merkel and several collaborators (Merkel 2004, Merkel et al. 2003). His group analysed political regimes by looking at different partial regimes. In each of them, potential ‘defects’ were associated with specific attributes to characterize the respective subtypes:

• A damaged electoral regime allows for characterization of a regime as ‘exclusive democracy’;3

• Limited civic rights, for example arbitrary access to courts or inequality before the law, and limited political freedoms such as the harassment of civil society lead to an ‘illiberal democracy’;

• Weak control powers and feeble horizontal responsibilities result in a ‘delegative democracy’ as described by Kubicek (see above);

• Damage to effective government power – no real power for those elected – leads to classification as an ‘enclave democracy’.

In the context of our article, Merkel’s types can be seen as proxies for all types of diminished democracy found in the literature. First, they focus on a particular element of democratic rule rather than on the democratic regime as a whole. Second, they attribute a malfunctioning in comparison to certain standards of (real or ideal) democracy. The attribute – this is the third point – describes this particular ‘defect’ but then semantically adapts it to express a particular democratic case as a whole.

Like in a mirror image, things are similar with regard to subtypes of authoritarian regimes. Obviously, the notion of ‘diminished subtypes’ needs to be used in purely analytical terms. We do not object to the notion of a ‘defective democracy’ because of the implicit understanding that a non-defective democracy is usually preferable in normative terms. Intuitively, calling a diminished subtype a ‘defective autocracy’ would give a signal that a normatively problematic regime exists in variations which are even worse. Subtype diminishment in the case of hybrid authoritarianism can in fact usually be equated with the opposite: Elements of autocracy open up and lead to more freedom or societal autonomy.

Since it is not possible to discuss all subtypes of autocracy here (see, for example, Shevtsova 2004, Hanson, Way and Levitsky 2006), I concentrate on one of the most prominent ones – the concept of ‘competitive authoritarianism’ as developed by Steven Levitsky and Lucan A. Way. In their view, competitive authoritarianism ‘must be distinguished from unstable, ineffective, or otherwise flawed types of regimes that nevertheless meet basic standards of democracy’ (Levitsky and Way 2002: 53). Translated into the figure of the previous section, the authors locate competitive authoritarianism within the field A1, but close to the line B1 which marks the crossover to a democratic regime. In competitive authoritarianism, some democratic elements, like a certain pluralism connected to elections, are present. In the end, however, competitive authoritarian regimes are defined by failing to offer democratic institutions as ‘an important channel through which the opposition may seek power’ (Levitsky and Way 2002: 54). Instead, ‘incumbents violate [democratic] rules so often and to such an extent that the regime fails to meet conventional minimum standards for democracy’ (Levitsky and Way 2002: 52). These violations concern not only elections, but also the arenas of legislation, the judiciary, and the media.

This understanding of a specific type of autocracy offers many parallels to the construction of democracy subtypes according to Merkel. Competitive authoritarianism is a ‘diminished’ subtype in the sense that one core element – elite selection – differs in character from the main type (where we would expect a top-down elite selection, completely controlled by incumbents). At the same time, the new subtype highlights this specific element while neglecting other features of this diminished authoritarianism. For example, the notion is less easily applicable to the judiciary sphere where ‘competition’ is hardly observable. To my knowledge, autocracy studies have not yet developed an integrated model of subtypes which would allow for more systematic categories.4 Instead, we can observe a turn towards metaphors like the ‘uneven playing field’ (see Way and Levitsky in this volume), which include the multi-dimensionality of diminished authoritarianism without being able to conceptualize it in a differentiated way.

While there are many parallels between diminished democracy and diminished autocracy, there also exists one major difference. Diminished democracies are implicitly seen as relatively long-lived regimes, with built-in defects of a structural nature. The electoral regime plays a crucial role because non-democratic developments in this sphere may swing the whole regime in an authoritarian direction. In such a case, the structural nature of democratic defects makes it relatively unlikely that such a trend may be reversed within a short time.

With regard to diminished autocracy, however, things are somewhat different. Since we are by definition dealing with regimes which allow for competition, it is not unlikely that the organization of acceptably free elections may lift a case above the electoral democracy threshold. If regimes are not completely closed, there is always a next election on the horizon. Of course, there exist different suggestions on how many free (and fair) elections need to be observed until a country may plausibly be classified as a stable democracy. However, we have seen that there are many diminished forms of democracy, and stability is not a precondition for all of them. Therefore, diminished authoritarian regimes are by definition close to becoming democracies. Indeed, one of the major aims of autocracy studies is to identify conditions under which this is the case.

Consequently, we find the scholarly opinion that competitive authoritarian regimes often oscillate between democracy and non-democracy (Howard and Roessler 2006: 368). Stating an oscillation as such does not change the character of competitive authoritarianism as a diminished subtype. Yet, if...