![]() PART I

PART I

The Economy of Exile![]()

Chapter 1

Leaving France

According to Jean Claude (1619–1687), the famous Huguenot minister from Paris who had taken refuge in The Hague, explaining the mass exodus of Protestants from France was straightforward enough. Huguenots went into exile for the sake of religion, because they could not bear to renounce their Protestant beliefs at the point of a sword. In his 1686 indictment of French religious policy, published anonymously as Les plaintes des Protestans, cruellement opprimez dans le Royaume de France, Claude argued that

the fear of the Dragoons, the horror of seeing their consciences forced, their children abducted, & of having to live henceforth in a land where there will neither be justice nor compassion for them, obliged every one to think of an escape, & to abandon all in order to save themselves.1

Huguenot refugees flooding the Walloon churches of the Dutch Republic confirmed Claude’s analysis that religious zeal was the reason they had left France. Although the dragonnades had initially forced them to convert, they hastened to explain that hiding their beliefs behind a façade of Catholic conformity had become untenable – the only solution was to go into exile. When in the summer of 1686 refugee Pierre de la Coste thus repented of his conversion to Catholicism before the consistory of the Walloon church in Utrecht, the elders mercifully welcomed him back into the Protestant fold, observing that ‘God having touched his heart with great contrition, he had searched with care and fortunately found the means to leave for these Provinces, in order to return to the profession of the true religion that he had so cowardly abandoned’.2

Yet tales of religious courage offer a rather one-dimensional perspective on the Refuge. They reduce the refugees to zealous Protestants who abandoned their homes for the sake of religion, while in fact going into exile was far more complicated. Certainly, the reason Huguenots left France was their desire for religious freedom, but as this chapter will argue, socioeconomic opportunities eventually determined who was able to go into exile and who stayed behind in France. Leaving home was not a decision that most refugees made overnight, because it raised a number of awkward questions: Where to go? How to get there? Where to find employment? In early modern Europe, sensible migrants did not light-headedly set out for the unknown, but first tried to get some answers – and for Huguenots pondering whether or not to leave France, the socioeconomic hurdles were not much different. The Revocation, in other words, was not a neat religious caesura that separated the devout refugees from the faint-hearted who converted to Catholicism and chose to remain in France.

This insight is not entirely novel. Migration historians, for instance, have argued that any clear-cut distinction between religious and economic migration is misleading, because religious refugees also consider their economic fortunes: they will choose destinations where they can market their skills, while it is mostly the young, skilled and well-educated people who move.3 Recent scholarship on the Refuge likewise acknowledges that besides religion, the socioeconomic status of Huguenots also impacted on the decision to go into exile. In her classic study of the Revocation Elisabeth Labrousse even went as far as to argue that ‘the choice to remain in France or to go into exile had very little or nothing to do with the religious fervour of those who made it’. After all, a large group of zealous Protestants decided to stay in France – most notably in the Cévennes, where they rebelled in 1702 – while many insincere Huguenots did go into exile, as they hoped to benefit from the privileges Protestant authorities were handing out to French refugees. Labrousse therefore suggested age, profession, geographical location and foreign contacts as the most plausible factors explaining migration, although she admitted that these were only ‘fragile conjectures’.4

The problem is that historians often lack the quantitative data to support the hypothesis that socioeconomic opportunities played a key role in the decision-making process leading up to exile. Yves Krumenacker, for example, in his study on Protestants in the Poitou, laments that his sources on the professions of those who left are ‘too lacunar to draw serious conclusions’.5 Didier Boisson, who studied the Huguenot communities in the Berry, likewise notes that ‘the sources do not clearly show the motivations of refugees, especially the preparation for their departure’.6 Michelle Magdelaine has been more fortunate: source-mining the registers of Huguenot refugees passing through Frankfurt, she calculated that the vast majority came from the Midi, and that most refugees were artisans, merchants, medical practitioners, soldiers and even peasants. Yet she does not explain these patterns in socioeconomic terms, arguing that the refusal to convert to Catholicism was the sole reason these people had left France.7

To enhance our understanding of why Huguenots went into exile or decided to remain in France, this chapter will scrutinise new source material from the towns of Dieppe and Rotterdam. The archives for both towns contain unique registers on the departures and arrivals of the Huguenot refugees, which allow us to trace into far more detail their migration pattern, and to discern the factors that explain their movements. As will become clear, some Protestants were indeed more likely to depart than others. The decision to leave, moreover, was hardly ever taken in a fit of religious enthusiasm, but a carefully considered move guided by socioeconomic possibilities abroad. Leaving France and settling abroad was thus as much a story of migration as it was a tale of Protestant perseverance.

Normandy Origins

One of the main migration routes taken by Huguenot refugees carried them from the province of Normandy to the port town of Rotterdam – with around 51,000 inhabitants, the third largest city in the Dutch Republic after Amsterdam and Leiden.8 This migration pattern is brilliantly revealed in the ‘reconnaissance register’ of the Walloon church. In the spring of 1686 the Walloon consistory of Rotterdam decided to start a separate register listing all the names, signatures and geographic origins of Huguenots who wished to make a so-called ‘reconnaissance’: that is, to make public amends for their conversion to Catholicism and attending Mass in France. Refugees first had to appear before the consistory ‘to show the grief that their Fall has caused them, to beg God for pardon, and to give the Church satisfaction’, and after a solemn promise never to regress again they were obliged to make a public confession in church.9 One of these refugees was Jean Migault (1644–1707), a former schoolmaster from the Poitou who arrived in Rotterdam in May 1688. He later noted in his journal that ‘all those of our group who had the misfortune to fall just as I had done, publicly repented for their mistake at the end of the sermon, confessing their sin before God and the Church’.10

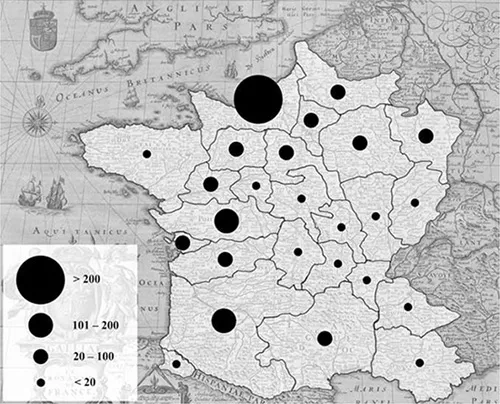

Map 1.1 Regional origins of Huguenot signatories in the reconnaissance register of the Walloon church of Rotterdam, 1686–1715.

Source: GA Rotterdam, EW 128, Register of abjurations and reconnaissances.

Migault was only one among many. During the period 1686–1715 an impressive 1,546 Huguenots signed the register, of whom 692 were men and 758 women. Most refugees also specified their home town or region; only 92 people failed to mention any place of origin, while in 29 cases the indicated town could not be pinned down to a region with any certainty.11 As shown in Map 1.1, the overwhelming majority of the remaining 1,425 refugees came from Normandy (588 Huguenots, 38 per cent of all signatures). Most other Huguenots had voyaged from towns in the ‘Protestant crescent’, those regions in France where most Protestants lived, stretching from the Poitou, Aunis and Saintonge in the north to Guyenne, Gascony and Languedoc in the south. Rotterdam also drew a sizeable proportion of Huguenot refugees from the northern provinces of Picardy and Champagne, as well as from the region around Paris.12

The eastern provinces, by contrast, are conspicuously absent from the register, because Huguenots from these regions were more likely to cross the Alps and settle in nearby Switzerland or the German lands. The majority of Huguenot refugees arriving in Geneva, for example, had fled from the Dauphiné, the Cévennes and the Languedoc, while almost 60 per cent of those settling in Berlin came from the Languedoc, Lorraine and Champagne, with smaller groups arriving from the Dauphiné and the principality of Orange.13 Even if Huguenots who had first gone east travelled on to the Dutch Republic, chances were they had already made their reconnaissance in one of the French-speaking churches en route. Claude Brousson the younger (1674–1729), for instance, fled from Montpellier to the Dutch Republic, but he first stopped by in Lausanne, where ‘I atoned for my mistake with Monsieur Combes, an old minister, who instructed me more specifically in the articles of our Religion’.14 The reconnaissance register also remains silent about those Huguenots who arrived before the Revocation or who had never converted, and thus did not have to make a reconnaissance. All in all, the Rotterdam register does not offer an even-handed reflection of Huguenot immigration, but it does serve as an excellent barometer indicating broader migration trends.

When we focus on the disproportionate number of Huguenots from Normandy, it turns out that most of them came from the towns of Dieppe and Rouen (see Map 1.2 below). Of a total of 588 Normandy Huguenots signing the Rotterdam register, more than half stated Dieppe as their town of origin (306 refugees, 52.1 per cent), compared to 152 from Rouen (25.9 per cent) and smaller groups from Caen, Luneray, Bolbec and Alençon. The preponderance of Huguenots from Dieppe and Rouen also struck the Normandy nobleman Isaac Dumont de Bostaquet (1632–1709), who upon arrival in Rotterdam in 1687 observed that ‘this beautiful and large town has become almost “Frenchified”, because of the retreat of a very large number of inhabitants from Rouen and Dieppe’.15

Situated on the English Channel, Dieppe was one of the largest merchant ports in seventeenth-century France. B...