- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Measuring Public Space: The Star Model

About this book

In the rapidly expanding public space debate of the past few years, a recurring theme is the 'loss of publicness' of contemporary urban public places. This book takes up the challenge to find an objective way to prove or disprove this phenomenon. By taking the reader through a systematic and multi-disciplinary literature review it asks the deceptively simple question: 'What is publicness?' It answers this by first developing a new theoretical approach - 'The dual nature of public space', and secondly a new analytical tool for measuring it - 'The Star Model of Publicness'. This pragmatic approach to analysing public space is tested then on three new public places recently created on the post-industrial waterfront of the River Clyde, in the city of Glasgow, UK. By seeing where and why certain public places fail, direct and informed interventions can be made to improve them, and through this contribute to the building of more attractive and sustainable cities. By adopting a multi-disciplinary approach to shed light on this 'slippery' concept, this book shows how urban design can complement other disciplines when tackling the complex task of understanding and improving the built environment's public realm. It also bridges the gap between theory and practice as it draws from empirical research to suggest more quantitative approaches towards auditing and improving public places.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction

1.0 WHY THIS BOOK

This book stems from a personal belief that public space plays a key role in building the sustainable, socially equal and liveable cities of tomorrow. We are greatly concerned today with the sustainable development of our fast urbanising society (Human Development Report 2007/2008, UN Climate Change Conference Copenhagen 2009) and with finding ways to improve our cities so that they become more socially cohesive, environmentally friendly and economically competitive. Through their multiple functions and various roles, public places1 are central to achieving urban sustainability, in all its three dimensions:

Firstly, from a social perspective, public places such as streets, parks, plazas, squares and so on, are the stages where new social encounters happen, where people relax and enjoy themselves together, in other words, where the city’s public social life unfolds. They connect the space of home and work/study thus providing the setting and the opportunity for the enrichment of a society’s public life. Of a special concern today is a worldwide noticeable increase in the control of ‘the public’ and the existence of a new wave of anti-immigration attitudes and policies on the background of the current economic crisis, such as in the recently conservative United Kingdom. The concept that Nancy Fraser coined of ‘multiple publics’ (1990) becomes therefore key to understanding the contemporary multi-ethnic city. When we think of the control of the public, we must ask ‘Which public?’ while when we discuss the creation of a public place for the public, we must ask ‘What kind of public?’ and ‘Who defines the public?’. In addition, the predominant phenomenon of the privatisation of public space (Sorkin 1992, Davis 1998, Zukin 2000, Atkinson 2003), coupled with an increased degree of control and surveillance measures (Lofland 1998, Davis 1998), especially after 9/11, has led to grave consequences, such as increased social exclusion and spatial injustice. It is held here that more inclusive and more democratic public places help a city’s social cohesiveness, which in turn contributes towards its sustainability.

Secondly, from an environmental perspective, well-designed public places support pedestrian routes and public transport connections over car-based developments. Car dependency, one of the most polluting factors in our cities, together with the increase in global warming and the fast growth of urban population, have slowly led to a radical change in our approach to city planning and design. This has involved prioritising more compact cities based on walking and an interconnected public transport networks and greener cities based on sustainable buildings, green belts and clean, renewable energy. By promoting parks and the greening of cities, as well as walking, cycling and public transport, public places contribute to a more environmentally friendly urban landscape. It is also held here that a more compact and greener city is a more sustainable city.

Thirdly, from an economic perspective, high quality public places are characterized by a high pedestrian footfall, supporting local businesses, especially shops, restaurants and bars, in the detriment of large suburban malls. At the same time, they act as promoters for a city’s image, develop social capital and help attract investment to an area, while also supporting tourism. A city with an attractive public image and with varied opportunities for tourists and residents alike to spend their leisure time is a more economically viable and competitive city and therefore a more sustainable one.

When one tries to research the publicness of places, it slowly becomes apparent that the public space concept itself is a fairly slippery term. This can be explained by the perception of publicness being subjective, by the complex nature of real public places and by the inherent ambiguous meaning of publicness. Firstly, on an individual level, public space is a subjective, personal construct and each individual will have a different view on what constitutes a good public space for him/her. Secondly, on a more practical level, the ‘real’, built public places are complex socio-cultural, political and environmental products of a social group. Each actor in the process of creating a public place will have their own conceptualisation of what makes a public space public and bring to the table different skills, experiences, motivations and objectives. Finally, on a theoretical level, the existence of various disciplinary understandings of public space creates much confusion around the meaning of the terms ‘public space’ and ‘publicness’ of space. The first aim of this book is therefore to bring some light in understanding what public space is.

At a first glance, the contemporary public space of our cities has become a highly contested and controversial topic (see Atkinson 2003, Raco 2003). Debates on the ‘politics of space’ (for example, the tension between surveillance and access rights to public space) continue to capture academic and public attention (see Lefebvre 1991, Flusty 2001, Mitchell 2003, Madanipour 2003, Kohn 2004), raising important questions of social justice, such as: ‘Who makes and controls public space?’ and ‘Who benefits from the development of new public space in the context of restructuring the city?’ There are even more pessimistic voices arguing for the breakdown of society and ‘the fall of public man’ (Sennett 1977) due to a change of people’s attitudes. From active participants in the life of the city, ‘the people’ have become passive spectators to the display of neoliberal and market-driven forces (Foucault 1986); the ‘public’ has been ‘pacified by cappuccino’ and lost its ability to fight for ‘social justice for all’ (Zukin 2000, Atkinson 2003). As a reflection of such concerns, a distinctive strand in recent urban design policy in the United Kingdom has been focused on urban design as making places for people (Urban Task Force 1999 and 2005, DCLG 2009, Carmona et al. 2003). As such, ‘the public’ has been the subject of increasing policy attention over such matters as the commodification of space; cappuccino urbanism and a focus on affluent consumerism; the privatisation of public space; the militarisation and securitisation of space through CCTV and other express security measures; exclusion from public space; the emergence of gated communities; the Disneyfication of public spaces; etc.

1.1 Public space – a multidisciplinary approach

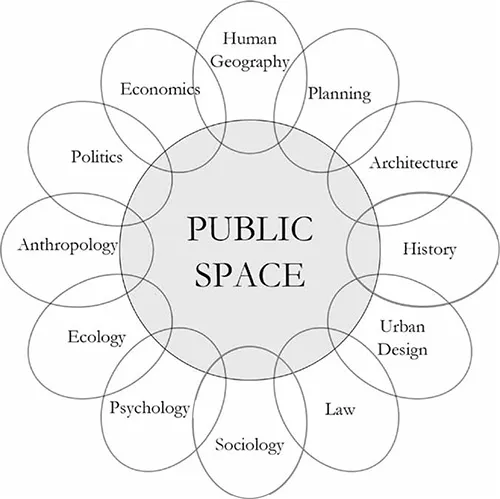

Apart from the field of urban design and planning, public space is also the subject of a growing academic literature from the social sciences and humanities (Carr 1992, Sorkin 1992, Mitchell 1995, Zukin 2000, Madanipour 2003, Massey 2005, Mensch 2007). Each discipline sees public space through a different lens, and with particular interests and concerns to the fore. Political scientists, for example, focus on democratisation and on rights in public space; geographers on ‘sense-of-place’ and ‘placelessness’; legal scholars on the ownership of and access in public places; sociologists on human interactions and social exclusion etc. The result is a diverse array of approaches towards understanding ‘public space’ (Figure 1.1).

What these various accounts seem to have in common though is a sense that something has been lost. Many of these voices come from the American academia, pointing out that a commonly accepted standard of ‘publicness’ of public space has been tainted by the intrusion of economics and politics of fear and control (Sorkin 1992, Mitchell 1995, Davis 1998, Zukin 2000). This gave this book its starting point – to question if indeed contemporary public places are less public than they could/should be. In order to do this, and clarify the concept of public space, this study proposes a new way to assess the publicness of space, both as a cultural and as a historical reality. Moreover, it proposes a new quantitative model to measure public places, the Star Model of Publicness. These ideas will be briefly introduced in the following section.

1.1 THE DUAL NATURE OF PUBLIC PLACE AND PUBLICNESS

As a distinctive part of the built environment, the main stage where the life of the community unfolds, public space is deeply intertwined with the beliefs, traditions, experiences, political views and what is generally understood as the culture of a particular society.

The existence of some form of public life is a prerequisite for the development of public spaces. Although every society has some mixture of public and private, the emphasis given to each one and the values they express help to explain the differences across settings, across cultures, and across times. The public spaces created by societies serve as a mirror of their public and private values as can be seen in the Greek agora, the Roman forum, the New England common, and the contemporary plaza, as well as Canaletto’s scene of Venice. (Carr et al., 1992: 22)

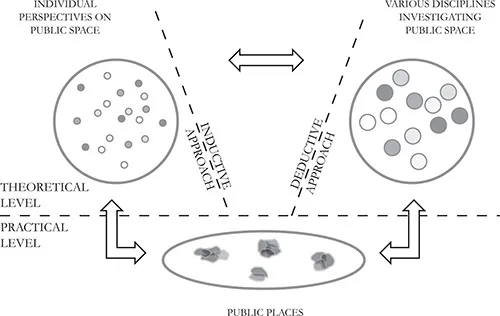

It can be therefore argued that reflecting broader political, economic and social concerns, a social group holds at a certain point in time a common understanding of what makes a public space public. This is then translated in the various public places built in the urban realm. If one could grasp this generally held view on the best practice of public places and determine what key characteristics are considered as giving a certain place its ‘quality of being public’ or ‘its publicness’, then this could be used as a standard for measuring different public places. But how to grasp this ideal? The approach taken here was to investigate the literature in the field, from as many disciplines as possible, in a deductive manner (see Figure 1.2).

1.2 Different approaches to studying public space

On one hand, this academic literature presents a large amount of information about a multitude of public places and as a result, common themes can be found that describe many of them. On another hand, the various professionals (architects, planners, politicians, lawyers, etc.) who are involved in the practical creation of public places are trained and educated in a common paradigm of place making, described in the scientific community. The commonly held view of what a ‘quality’ public space is, being part of this paradigm, will be translated in practice into similar characteristics shared by all public places. This is the understanding of a public place as a cultural artefact and its publicness as a cultural reality. We are aware that the meanings of the terms culture and cultural can be largely debated; here by describing a public place as a cultural artefact, we understand its creation as a reflection of society’s views, beliefs, norms and ideas regarding what a public place should be. There are noticeable differences between Trafalgar Square and Tiananmen Square; however, different societies share common traits and it would be very interesting to see how these are translated in the creation of public places around the world and whether there is a universal model for ‘publicness’. For the time being, the fact that publicness is a cultural reality means that here, according to the consulted literature, an ideal for public space can be grasped only as a reflection of the western thought in general, at the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first. This anchoring in time is due to the fact that, at the same time with being a cultural reality, a public place is also a historical construct and its publicness a historical reality. As the western society changed in time, so did the understanding and the physical representations of public space; as such, during different time periods, public places were created according to different ideas and ideals of publicness. The ideal of publicness of the ancient Greeks reflected in the agora where women, foreigners and slaves were not allowed to take part (Mitchell 1995) seems inappropriate for the contemporary western society’s values. This means that an ideal public space and a standard for its publicness can only be defined for public places, built in the UK and generally in the western world, in the last 50 years or so.

Publicness as a historical reality is understood here not only on this macro-level, but also on a micro-level. This means that at a certain point in time, each public place’s publicness results from a particular historical process of production, commonly known as the land and real estate development process. It has to be acknowledged from the very start that in this book, publicness is conceptualised as something ‘out there’, something measurable, independent of the human consciousness. The critical realist approach taken here asserts therefore that firstly, there is a real thing called ‘publicness’ and secondly, that this can be understood by investigating the structures and processes that generate this quality of public places. There is no such thing though as a perfect observer of the reality, as the cultural background and experiences of each of us influence the ways in which publicness is conceptualised. Therefore publicness can always be grasped from a subjective point of view. Each individual has a slightly different way of perceiving what a public space is, from one’s experience of different public places and the personal meanings they are associated with. This indicates that no public place can be a perfect reflection of the commonly held ideal of publicness because public places are created through the interaction of various individuals with their own different understandings of what public space is. Each public place will reflect a different degree of publicness according on one hand to how the various actors involved in its development process understand publicness and on another hand to the general historical context that governs the actions of these actors.

The author thought that two approaches could be taken when trying to delineate a standard of publicness. Apart from a deductive approach (Figure 1.2) adopted here, there could be an inductive study undertaken where a large number of individuals’ conception of publicness would be investigated, commonalities found and an ideal of public space defined. Examples of research on the different perceptions and meanings that people have in relation to public space are Kevin Lynch’s Image of the City (1960) and Jack Nasars’ The Evaluative Image of the City (1998). However, these studies also stress that the publicness of a public place is a perceived reality, based on each individual’s memories, experiences and personality. Therefore, even though a standard of publicness was defined through the Star Model approach, the author understands that publicness is not only a concept capable to be measured and analysed, but also a subjective construct. In terms of making real public places, this means that we can always aim to create more public places for more publics but a public place for all publics is a utopian dream.

1.2 A NEW MODEL TO MEASURE PUBLIC SPACE

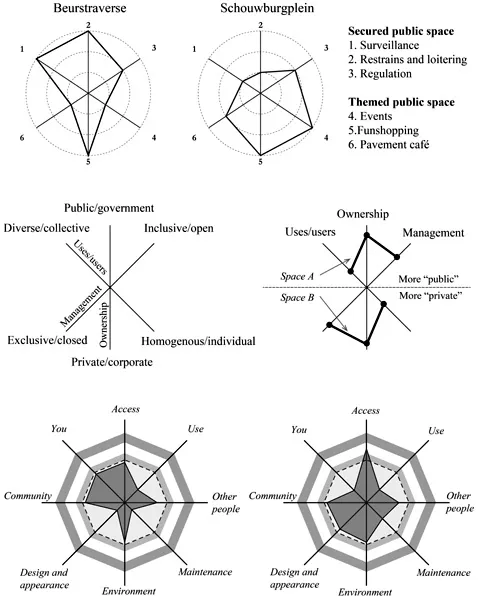

In order to understand and measure the publicness of a public place as a snapshot, reflecting a cultural reality at a certain point in time, the Star Model was created. This however was built upon several original and valuable attempts of analysing and quantifying different aspects related to the publicness of space as shown in Figure 1.3.

1.3 Previous attempts to measure public space

Sources: (top) Van Melik, R., Van Aalst, I. and van Weesep, J. (2007) ‘Fear and fantasy in the public domain: the development of secured and themed urban space’. Journal of Urban Design, 12(1), pp.25–42, Routledge. (middle) Nemeth, J. and Schmidt, S. (2011) ‘The privatization of public space: modeling and measuring publicness’, Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 38(1), pp.52–3, Pion Ltd. (bottom) CABE Spaceshaper a publication by former CABE.

Van Melik et al. (2007) looked at indicators related to one dimension of public space, management, and were concerned with comparing two opposed types of managed public places: ‘secured’ and ‘themed’ ones. Their intuitive attempt at quantifying one of the key issues related to public space has been pivotal at the start of this research. Nemeth and Schmidt (2007) have also looked at the management aspect of public space and attempted to create a ‘methodology for measuring the security of publicly accessible spaces’ (Nemeth and Schmidt 2007). Their work has advanced that of the Dutch authors quoted above because they include the dimensions of ‘design’ and ‘use’ in a more comprehensive model of assessing public places. While an important part of their ideas and aims are shared in this study, their model was found as looking not specifically at the ‘publicness’ of public places but only from the point of view of control in public space and consequently all their indicators subscribe to this explicit agenda. At the same time, although their model was deemed as contributing significantly to a more pragmatic interpretation of public space, it did not manage to capture the multi-dimensional and complex nature of ‘publicness’. In consequence, it could not have been used here. This was due largely to it being quite a general study, with indicators taking only the values 0, 1 and 2 and looking at a large sample of over 100 of New York’s public places. In addition, although they include the dimension Use/Users they do not offer a way of measuring this. All this considering, their work is an important standing stone for the present book, making a contribution in understanding and depicting public space as a multilateral concept while it also testifies for ‘the need of more pragmatic research’ (Nemeth and Schmidt 2007: 283) in the field of public space.

The importance of finding a practical way of assessing the success or failure of public places is also demonstrated by CABE’s (2007) publication of the Spaceshaper. This has been described as ‘a practical toolkit for use of everyone – whether a local community activist or a professional – to measure the quality of a public space before investing tim...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Dedication

- List of Illustrations

- List of Tables

- List of Abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- PART I CONCEPTUALISING PUBLICNESS

- PART II MODELLING PUBLICNESS

- PART III ASSESSING PUBLICNESS

- Annexe 1: Interview Pro-forma

- Annexe 2: Observation Days and General Weather Conditions

- Annexe 3: Non-time Dependent Observation Pro-forma

- Annexe 4: Time Dependent Observation Audit Pro-forma

- Annexe 5: Diversity and Number of Activities Recorded during Observation in Pacific Quay

- Annexe 6: Diversity and Number of Activities Recorded during Observation in Glasgow Harbour

- Annexe 7: Diversity and Number of Activities Recorded during Observation in Broomielaw

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Measuring Public Space: The Star Model by Georgiana Varna in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & City Planning & Urban Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.