![]()

PART I

Challenging Cultural and Social Traditions

![]()

Chapter 1

The Boundaries of Womanhood in the Early Modern Imaginary

Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks

One afternoon in 1594 the Italian scientist, collector, and physician Ulisse Aldrovandi visited the home of a wealthy friend in Bologna. Among other visitors at the elegant home was Isabella Pallavicina, whose noble title was Marchesa of Soragna, a city near Bologna. With the Marchesa was Antonietta Gonzales, the young daughter of Petrus Gonzales. Like her father and like most of her sisters and brothers, Antonietta Gonzales suffered from a genetic abnormality now known as hypertrichosis universalis, which meant much of her body was covered with hair. Aldrovandi studied the little girl carefully, and later noted:

The girl’s face was entirely hairy on the front, except for the nostrils and her lips around the mouth. The hairs on her forehead were longer and rougher in comparison with those which covered her cheeks, although these are softer to touch than the rest of her body, and she was hairy on the foremost part of her back, and bristling with yellow hair up to the beginning of her loins.1

This report, along with woodcuts of Antonietta and other hairy members of her family, was included in Monstrorum Historia, an enormous catalog of human and animal abnormalities mostly written by Aldrovandi, though not published until 1642, long after his death. Two hairy girls are shown there, described as age eight and age twelve (Figure 1.1).

Aldrovandi’s friend Lavinia Fontana, a painter from Bologna known for her portraits of nobles and children, may have been at the house that day as well, for she later painted Antonietta’s portrait in oil, which now hangs in the castle of Blois in France (Figure 1.2). In the painting, Antonietta holds a paper that gives details about her life:

Don Pietro, a wild man discovered in the Canary Islands, was conveyed to his most serene highness Henry the king of France, and from there came to his excellency the Duke of Parma. From whom [came] I, Antonietta, and now I can be found nearby at the court of the Lady Isabella Pallavicina, the honorable Marchesa of Soragna.

Figure 1.1 Woodcut of a Gonzales sister, from Ulisse Aldrovandi, Monstrorum historia (1642). Memorial Library, University of Wisconsin-Madison. Author’s photograph. The caption reads: “Eight year old hairy girl, the other sister.”

Lavinia Fontana also drew a sketch in pencil of a little hairy girl, perhaps Antonietta, or perhaps her older sister Francesca, for she looks quite different from the girl in the oil painting.2

Figure 1.2 Lavinia Fontana, Portrait of Antonietta Gonzales (1590s). Chateau Blois, France. © RMN — Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY.

The story of the three hairy Gonzales sisters takes us from their father’s birth in the Canary Islands to their residence at the court of Henry II and Catherine de Medici in Paris to their move to the Farnese courts in Parma and Rome and, finally, to a small Italian village where they disappear from history.3 At various points on that journey, physicians and courtiers studied and described members of the family, and naturalists and artists created their portraits in oil, pencil, woodcut, and engraving. Those descriptions and portraits were examined by others, who in turn depicted members of the family verbally in letters, diplomats’ reports, scientific works, and newssheets, and visually in miniatures, watercolors, and emblem books. The only sources that survive from any member of the family are a few letters from one of the brothers, who served as a minor official for the Farnese family. These contain no discussion of his hairy condition or what it meant to him. The painters, physicians, and scientists who contemplated members of the family, saw their portraits, or heard about them did discuss their hairiness, however, and used this as a springboard to speculate more broadly about the role of divine providence, the order of the universe, the balance between nature and nurture, and a number of other issues.

The three Gonzales sisters left no historical record themselves, but their persons and their portraits led early modern artists, scientists, and physicians to consider broader issues and in particular to confront a very postmodern question: were they women? That is, were they within the borders of womanhood?

I am labeling this question “postmodern” because concern with the meaning of “woman” has been a key issue in feminist analysis since the linguistic turn of the 1980s. At that point, the only recently delineated distinction between “biological” sex and “socially constructed” gender became contested. Challenges to that distinction came from biologists, anthropologists, and intersexed individuals, and also from historians of women. The latter increasingly emphasized differences among women, noting that women’s experiences differed because of class, race, nationality, ethnicity, religion, and other factors, and they varied over time. Because of these differences, some wondered, did it make sense to talk about “women” at all? Was “woman” a valid category whose meaning is self-evident and refers to an enduring object, or was it simply a socially constructed and historically variable conceptual category grounded in discourse?4

Although she explicitly does not consider herself a postmodernist, Hilda Smith has also long challenged historians to consider the categories through which women have been understood and defined and through which they have understood and defined themselves and the world around them. In All Men and Both Sexes: Gender, Politics, and the False Universal in England 1640–1832, she highlighted ways in which universal terms such as “man” or “human” actually excluded women.5 As she notes, when guild records, parliamentary debates, educational treatises, advice literature, or periodicals referred to “all men,” they meant men of all ages and social stations. Women were never similarly differentiated, but categorized only according to their gender in the phrase “both sexes.” This essay continues this gendered analysis of conceptual categories but focuses on an instance in which early modern people did differentiate among women. It explores ways in which the hairy Gonzales sisters challenged early modern conceptualizations of the boundaries of womanhood, particularly in terms of how these intersected with other approaches to understanding and organizing the world. I will focus on two particular boundaries: that between animal and human, and between civilized and “wild.”

First, the boundary between animal and human. Members of the family were often compared with animals: on seeing the young Petrus Gonzales in Paris, a representative of the Duke of Ferrara compared his hair with the fur of a sable and noted that it smelled good.6 In the Monstrorum Historia, Aldrovandi describes Petrus Gonzales as “not less hairy than a dog,” and Antonietta’s skin as “similar to that of an unfledged bird.”7

Aldrovandi was a collector as well as a scientist and author, with a cabinet of curiosities that eventually held more than 18,000 items arranged in huge display cabinets, including 8,000 paintings done in watercolor and tempera by a group of artists—including Lavinia Fontana and several other female artists—commissioned by Aldrovandi and working under his direction. Among the paintings of plants, animals, rocks, and exotic creatures are two portraits of one of the Gonzales sisters. In one, she looks exactly like Antonietta in Fontana’s portrait: a young woman with flowers in her hair, wearing a pink brocade dress and holding a piece of folded paper. We do not know if Lavinia Fontana did the tempera as well as the oil painting, but it is clear that either one is a copy of the other or both are copies of a lost original, as two artists could not have imagined the little hairy girl so similarly.

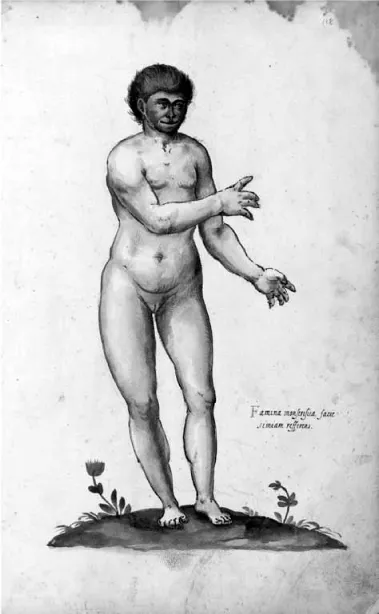

The caption on the tempera situates its subject very differently than does the paper on Fontana’s oil painting, however. Instead of flattering references to the rulers of three different courts, in which Antonietta or members of her family had lived—Paris, Parma, and Soragna—it says simply: “A hairy woman of twenty years whose head resembles a monkey, but who is not hairy on the rest of her body.” (The artist had evidently not read Aldrovandi’s description of the actual little girl, which indicated that she was “bristling with yellow hair up to the beginning of her loins.”) A second tempera painting in Aldrovandi’s collection also shows a young woman with a hairy head, but in this one she is naked. Her body is hairless and her face is hairy, matching the description of the girl in the first tempera painting, but in her face and posture she looks nothing like her, in that she has a more animalistic face and claw-like fingers (Figure 1.3). The caption includes misspelled words, suggesting that the artist who painted this was not a skilled Latinist, and this moves her even further from the human: “Monstrous female, whose face recalls that of a monkey.” In this she is no longer “mulier,” woman, but “femina,” female (or actually “famina” in the artist’s misspelling).

The Flemish artist Joris Hoefnagel appears at first glance to have followed the pattern of comparing members of the Gonzales family to animals; he included paintings of the family in his four-volume emblem book, Elementa depicta, painted during the 1580s. They are labeled there as “rational animals” in a volume that is otherwise devoted to insects.8 In both visual and verbal depictions of the family, however, Hoefnagel breaks with the pattern. On the first vellum sheet is a picture of Petrus Gonzales and his unhairy wife Catherine, he wearing a scholar’s blue robe with black sleeves and she a black dress with a tight-fitting bodice and lace collar. On the second vellum sheet are two of the Gonzales children in brilliant pink gowns. Like her mother, the girl wears a gown with a tight bodice and lace collar, albeit in fancier fabric than that of her mother as well as a necklace with a cross and a large teardrop pearl, and a hair decoration that entwines flowers, pearls, and her own hair. Like his father, the boy is wearing a long gown, with clasps running down the front—a miniature version of the standard scholars’ robe (Figure 1.4). Thus, their clothing links the family with learning, respectability, and piety—connections further enhanced by Hoefnagel’s framing of the family members’ ovals with verses, mostly from the Bible.

Figure 1.3 Tempera painting of a girl from Aldrovandi’s collection, now in the Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna. Author’s photograph. The caption reads: “Monstrous female, whose face recalls that of a monkey.”

Figure 1.4 Joris Hoefnagel, miniatures of the Gonzales children from Elementa depicta (1580s). Gift of Mrs. Lessing J. Rosenwald. Image courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Opposite Petrus and Catherine in Hoefnagel’s emblem book—that is, on the reverse side of the previous page—is a poem written by the artist in Petrus’ voice:

I am Petrus Gonsalus, cared for by the king of France

I was born in the Canary Islands,

Te...