1.1 Introduction

Macroeconomics studies an economy as a whole and builds relationships between aggregates. It develops a conceptual framework in which to understand issues like varying rates of inflation and output growth across time periods and countries, and how policy affects these outcomes. Open economy macroeconomics studies the great macroeconomic questions when economies become more open to trade and to movements in financial capital. That is why the field is sometimes called international finance.

There was resurgence in the subject as economies that had been closed after the experience of the Great Depression gradually opened out. There were bursts of growth in hitherto stagnating areas as more countries embraced globalisation, but a number of currency and financial crises also occurred, not only in emerging and developing economies (EDEs) where they were regarded as habitual, but also emanating from an advanced economy (AE) – the United States – and spreading to others such as the United Kingdom and Europe, in what has come to be known as the global financial crisis (GFC). The slowdown that followed proved remarkably persistent. Therefore, old questions of stability became important once again, but new questions also arose, as did new ways of addressing them. There was resurgence in the subject also, as it drew on new tools developed in macroeconomics and in finance.

Freer flows of capital have implications for exchange rate regimes and the effectiveness of macroeconomic policies. For example, in an open economy, domestic interest rates are closely linked to international interest rates through the exchange rate regime; more flexible exchange rates influence domestic wages and prices; there can be wealth effects through the accumulation of foreign assets.

In recent years, events and analytical frameworks in the area were both in flux. Those developing economies that opened out, reformed and gave markets a greater role came to be known as emerging markets (EMs). By 2014, EDEs as a group accounted for 57 per cent of the world gross domestic product (GDP), up from 46 per cent in 2004, and the IMF included 152 countries in this group. Asia accounts for some of the largest and fastest growing countries, and therefore requires careful study. Crucial simplifications in frontier frameworks of analysis made them more applicable to EDEs, but adaptations were required especially for structural aspects of Asian developing economies, which were neglected even in attempts to adapt modern monetary frameworks to developing economies. For example, Development Macroeconomics by Agenor and Montiel (1999), a pioneering macroeconomics textbook for developing economies, is more applicable to Latin America.

Early work on structuralist macroeconomics introduced developing economy features into Keynesian frameworks, but not into the modern forward-looking approach, which is what this book attempts. For example, structuralist macroeconomics often worked with two sectors (Rakshit, 2009). While dualism, especially in labour markets, has persistent macroeconomic outcomes, modern tools of aggregation allow it to be modelled consistently using aggregate demand (AD) and supply curves (Aoki, 2001), as we will see in Chapter 11. The idea that agriculture is supply determined with price adjustment and industry is demand determined is not adequate in a more open economy with freer imports, which will impact prices.2

The book presents three types of analytical frameworks, as well as concrete applications, largely based on Indian experience: (1) the simple concept-based frameworks that serve to train and anchor intuition; (2) a more rigourous anchoring framework based on dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE), which has evolved as a widely used benchmark; and (3) a variety of special models used to analyse specific issues or events, such as currency crises.

The GFC has resulted in a questioning of the DSGE frameworks. These are widely used as a benchmark in open economy macroeconomics. Therefore, this chapter begins with a discussion of appropriate evolution in macroeconomic frameworks, including the DSGE.

In the remainder of the chapter, Section 1.2 examines general methodological principles, or the nature of reasoning in macroeconomics, and develops the centrist position that will be followed in the book. Section 1.3 outlines the new issues and perspectives modern research has thrown up in open economy macroeconomics, which will be expanded on in later chapters. Although the general analytical framework remains the same, special questions arise in EDEs. We discuss adaptations that may be required or special models that may need to be built for EDEs in Section 1.4 and illustrate these by applying abductive reasoning to derive the aggregate demand and supply structure, consistent with observed combinations of Indian growth and inflation. Section 1.5 concludes with brief overviews of the book.

1.2 Between deduction and induction

Macroeconomic theories are being constantly surprised by events they are unable to predict, prevent or even understand. The GFC was an illustration of this, as were the stagflation of the 1970s and the unemployment of the Great Depression. None of these could be understood in the prevailing analytical frameworks. Since theoretical modelling gives a causal structure that should hold not only in current, but also in future data sets, this would seem to be a major flaw.

But macroeconomics is intrinsically an empirical relationship between aggregates, and therefore cannot build a watertight deductive universe, as is possible in theories about individual behaviour. These can be deduced from behavioural axioms without reference to facts, although their aim is also to explain real-world behaviour. Macroeconomics has to work with aggregates, distant from individual behaviour, and therefore cannot escape induction, which is ultimately falsifiable. But does this mean it lacks a theoretical foundation?

Macroeconomics does, however, have a non-trivial logical structure in addition to the use of induction. Learning is based on the general methodological principle of abduction, which is a mixture of deduction and induction. There is a substantive role for deduction, while the interplay with induction creates relevance, in a stimulating interaction between analysis and events. Analysis develops in response to puzzling events that cannot be understood in the existing framework. And it defines new concepts and generates facts.

Abductive reasoning is based on both outcomes and analysis. Abduction and induction derive conclusions from outcomes, unlike deduction which derives them from assumed premises. But abduction reasons backwards from the outcome, to deduce the framework with which it is compatible (Goyal, 2016).

Greater generality is a sign of progress. This does not mean that an in-depth analysis of a specific issue is given up, only that all aspects relevant for the question asked are included in the analysis.

For example, Keynesian demand-determined output was a reaction to the failure of classical economics to explain the involuntary unemployment of the Great Depression. But the neglect of the supply side it led to made the stagflation following the 1970s oil shocks a puzzle. This, in turn, led to a reaction away from demand-led theories towards supply-side real business cycle (RBC) DSGE-based theories that made monetary and fiscal policies largely irrelevant. But neglecting these major aspects reduced relevance. Moreover, DSGE models were unable to explain outcomes without adding different kinds of frictions.

The New Keynesian Economics (NKE) School explored the sticky prices and industry structure that allowed demand shocks to be non-neutral, while retaining forward-looking behaviour. This evolution illustrates the response of theory to facts. Similarly, the GFC forced more analysis of the interaction between macroeconomics and finance. But overreaction to recent events, questioning the entire framework, can hurt progressive evolution.

While the focus of the discussion has been on the absence of finance in DSGE models, interesting issues have risen about the impact of financial malfunction on the relative effectiveness of monetary versus fiscal policies and of bringing a macroeconomic view of systemic effects and spillovers to bear on financial regulation. The chapter and the book discuss these issues. While finance has to be added to macroeconomic models, it is equally important to add macroeconomics to finance.

In macroeconomics, stylised facts generate theory, which organises facts. Anomalies generate new theories. There is a chain from analysis to facts to analysis. The methodology is neither deduction nor induction alone, but a combination of the two that Peirce christened abduction:

The surprising fact, C, is observed,

But if A were true, C would be a matter of course,

Hence, there is a reason to suspect A is true

Peirce 5.189, Hoover (1994, p. 301).

Both abduction and induction belong to ampliative inference, which justifies conclusions on the basis of specific outcomes. Explicative inference, by contrast, derives conclusions from assumed premises. This includes deductive logic-based theories, such as classical logic, which starts with a major premise: for example, ‘All humans are mortal’ includes a minor premise ‘I am a human’ and deduces to the conclusion ‘Therefore I am mortal’. Induction works by accumulating evidence, for example, instances of mortality. But since, without deduction from premises, even one counterexample can upset a conclusion, inductive knowledge is temporary. For example, the observation of black swans when the continent of Australia was discovered upset the inductive inference ‘all swans are white’. That is why, in econometrics, which is an inductive science, hypothesis can only be falsified. They can never be proved.

Abduction, however, shares features of deduction because it uses critical logic. But it is not deduction. If abduction was only disguised deduction, it would commit the fallacy of affirming the consequence. But it reasons backwards from the consequence. The derivation of Kepler’s laws of motion is an example of how abduction works. Kepler observed certain surprising patterns (C). If planetary orbits were elliptical (if A were true), the patterns followed (then C). So, he concluded the orbits were elliptical, deducing backwards from the facts to the framework. Similarly, if a contraction in demand is surprisingly observed to affect output much more than it affects price (if C), such an outcome would be a matter of course if a particular structure of aggregate demand and supply hold (then A). In Section 1.5, we apply such reasoning to derive the structure of Indian aggregate demand and supply.

So, abduction is a weak form of inference. Sense perception is a limiting case of abduction. All ideas start with abduction. It is detective work using facts that do not fit into preconceptions. This is what Sherlock Holmes did when he reasoned that some external factor had silenced it, from the surprising fact that the dog did not bark. Such reasoning explained the anomalous event.

Abduction is more than a Lakatosian defensive heuristic, since conceptual frameworks do change substantially in response to anomalies. But it is less than a Popperian falsification, since an old hypothesis can be modified and need not be discarded. Parts of old frameworks normally need to be retained for more generality. Abduction differs from inductive inference such as used in econometrics, where a hypothesis can only be falsified, never proved to be true, in that a process of deductive thinking develops the framework, which is consistent with facts, but which can be rejected by new facts.

Macroeconomics is criticised for being constantly forced to accommodate new facts. But this is a valid process of scientific discovery, as long as old theoretical frameworks are significantly expanded and explain the new as well as old facts.

For example, the classical framework, in which supply determined output because flexible prices cleared markets, could not explain the involuntary unemployment of the Great Depression. The Keynesian framework, however, explained this since output was demand determined; therefore excess supply could persist. So it was accepted and led to the development of new facts – concepts of national accounts. The whole apparatus for measurement of output and its components was a consequence of the framework.

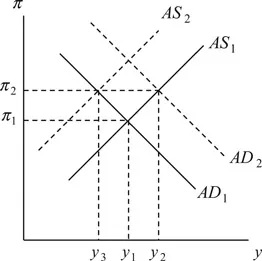

But the focus on aggregate demand (AD) and neglect of aggregate supply (AS) made the stagflation that followed the oil shocks of the early 1970s a puzzle. If output was demand determined, higher growth (y) and inflation (π) should occur together, as higher demand raised output and generated inflationary pressures. In Figure 1.1, where AD and AS curves are drawn in growth and inflation space assuming a positive trend in inflation and in growth rates, the equilibrium π1, y1 should shift to π2, y2 when demand rises. Since inflation and output both rise, however, this does not explain stagflation. But once aggregate supply is also considered, an upward shift of the AS curve allows a fall in growth and a rise in inflation to occur together. That is, the equilibrium π1, y1 shifts to π2, y3, a point of lower growth yet higher inflation. Analysing the role of demand explained low growth, but bringing in supply again explained the combination of low growth and high inflation – stagflation. Note, a framework that includes demand and supply is more general.

1.2.1 Progress as more generality

Figure 1.1 Understanding stagflation

Compared to the early post-Keynes focus on demand, itself a reaction to a sole focus on supply, oil shocks forced more analysis of the supply side, leading to more generality. The theoretical framework used became more comprehensive also, since the gap between RBC and NKE3 was smaller compared to that between Keynesians and monetarists – there was some sharing of ...