![]() PART I

PART I

Improved Access![]()

Chapter 2

Major Issues in the Global Mobility of Health Professionals

Robyn R. Iredale

Background

The international mobility of health professionals has increased markedly in recent years and has come to include very different and complicated patterns. One would be hard pressed to find a country that was not impacted by mobility, somehow, in its efforts to provide accessible, quality health services.

The movement of health workers, especially doctors, began in the colonial era when doctors and other health professionals from Europe provided services to the colonies.1 Later this movement reversed as doctors moved from the former colonies to the former colonial powers in the quest for higher education and better opportunities. From the 1960s this movement grew, as part of what Connell (2010: 40–44) describes as the second phase of migration and the globalization of health care. Migration also commenced to other countries, such as Australia, Canada and the USA, with the end of their discriminatory immigration policies. Mejia et al. (1979: 399–400) state that by the early 1970s ‘about 6 per cent of the world’s physicians (140,000) were located in countries other than those of which they were nationals’.

In Connell’s third phase, globalization, movements have escalated and expanded to include large numbers of doctors, nurses and nursing aides (Connell 2010: 48). The patterns have become increasingly more global and more complex. In Asia, India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Nepal and Bangladesh have been joined by a range of other countries, notably the Philippines, China, Vietnam, Indonesia and Malaysia, as major sources of health workers. In Africa, Egypt, Zimbabwe, Botswana, South Africa and others have become sources of doctors and nurses and the Caribbean has become a notable supplier of skilled health workers. Flows have also escalated from more developed countries, such as Australia, New Zealand and Finland.

Some of the sending countries lack adequate resources to pay higher wages, upgrade facilities, provide promotional opportunities or hire enough staff to meet their real needs. Thus many health workers are under pressure and look for opportunities to leave. At the same time, some governments see overseas labour deployment as a means of siphoning off surplus labour or as a way of earning valuable foreign exchange (for example, Myanmar, Philippines, India). In countries such as India, Pakistan and the Philippines there are more health professionals trained than are required and/or existing health workers retrain for international labour markets (for example, doctors retraining as nurses).

English-speaking countries are the major destinations for skilled health workers, though the Middle East, other parts of Asia and elsewhere have also become significant destinations. Once particular flows of migrants emerge, they tend to spawn further movements as people learn more easily about overseas opportunities and have friends and family who can smooth their adjustment in the destination country. Migration can, therefore, be supply-driven when skilled workers migrate to find their own jobs. At the same time, destination countries have a growing range of policies, visas and programmes to enable the entry of health workers in growing demand – due to aging, increased expectations, the rise of private facilities, inadequate training and high attrition rates. The role of recruiters, which include governments and private companies, has become extremely important as they advertise widely, interview offshore and provide assistance with migration applications and relocation costs. This makes migration much easier.

At the same time as developed country demand has been increasing, so has demand in developing countries. More rapidly growing populations, the rise of HIV/AIDS and other non-communicable diseases, aging, changing family structures, rising expectations as a result of education and access to television have all had an impact on the demand for health workers. Supply has simultaneously been affected by a shortage of finance for training programmes, high attrition rates (especially in countries with high rates of HIV/AIDS), out-migration and preference for other occupations.

Movements are both permanent and temporary. Temporary movement includes the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) Mode 4 movements whereby the movement of natural persons as service providers is promoted under the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) trade arrangements. GATS Mode 4 movement is for a definite period and cannot transform into permanent residency, whereas some temporary movement ultimately becomes permanent.

There are three main sets of forces at work in all mobility: the sending countries and their interests; the receiving countries and their shortages, conditions and treatment of overseas trained workers; and migrants’ desires for better pay, self-improvement and a chance to upgrade their skills. Key stakeholders are involved in all three. The challenge is how to retain the right to free movement of all individuals while at the same time ensuring that all people, especially those in sending countries, have access to an adequate and appropriate health care system. Mobility may lead to shortages at home but it is not the only factor: insufficient training opportunities, lack of interest in the occupation and high mortality (due, for example, to HIV/AIDS) are other possible explanations. Mobility, however, can compound an existing shortage. Connell (2010: 47) argues that:

Health workers were the forerunners in the gradual globalisation of skilled migration and, then as now, their migration was of greater concern than other skilled international migration flows, just as the idea of a brain drain was largely centred on the mobility of health workers.

It is debatable whether they were the forerunners but the impact of these migration flows on the health systems of both sending and receiving countries, and on the workers themselves, has raised growing concern at a variety of levels – national, regional and international. This chapter will examine the emergence of these concerns and identify the major issues that are impacting on the delivery of quality services. The focus will be on developing countries as they are in the most dire need and they are at risk of not meeting their obligations to provide universal access to even basic services. The possible options for national governments to alleviate shortages and concerns about the quality of their health workforces will be discussed.

However, the paucity of service providers in some of the poorer countries and the threat that this poses to the viability of their health systems is of grave international concern. International actions will be critically examined and the vital importance of receiving countries becoming more self-sufficient will be proposed as the most important policy step that needs to be undertaken.

Rising Concern and Research into the Mobility of Health Professionals

The National Level

Concern about health workforce issues is widespread and has long been the subject of enquiries, research and government reports in some of the more industrialized countries. The issues vary from place to place but mainly stem from the political pressure that is brought to bear in the absence of the provision of adequate and appropriate health care services. These issues need to be understood as they are what is driving the global increase in skilled health worker flows.

In more developed countries this often relates to actual or relative shortages, shortages of particular types of skilled health workers (for example, specialists, General Practitioners (GPs), nurses, aged care workers, and so on) or shortages in particular areas. Countries such as Australia, Canada, the US and the UK have long histories of shortages of health workers and of bringing in overseas trained workers – either by direct recruitment or by dint of their wider immigration policies. The USA with the largest number of doctors and little loss to international migration is expected to have a projected shortage of 200,000 doctors by 2020 (Cooper and Aiken 2006) and this has been the focus of their attention.2

Australia has experienced geographical and particular specialty shortages for a long time but, since the late 1990s, the situation has become more serious. A major change occurred after 1996, driven by the severe shortage of doctors in disadvantaged and rural and remote areas and subsequent employer demand. There was a marked policy shift and a rapid rise in temporary arrivals on 422 visas (medical practitioner temporary – ended in June 2010), 442 visas (occupational trainee) and 457 (temporary business long-stay) visas. The diversity of sources grew and by 2001 temporary recruit doctors were arriving from over 27 countries, with the major sources being UK/Ireland, India, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, China and Germany (Hawthorne 2007). At this time Australia was unusual, as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2007a: 191–192) points out.

Very few countries have specific migration policies for health professionals. Australia is one major exception. The medical practitioner visa (subclass 422) allows foreign nationals, who are medical practitioners, to work in Australia for a sponsoring employer for a maximum of four years. Since April 2005, however, medical practitioners can also apply to the general program for Temporary Business Long Stay (subclass 457).

Australia and New Zealand have tinkered with their migration selections points systems to better target permanent migrants who are in occupations that are in shortage. For example, the Australian government introduced changes to its priority processing arrangements and revised its shortage occupation list. A new ‘Critical Skills List (CSL) was announced, comprising 58 occupations identified as remaining in shortage …’ (OECD 2010: 57–58). ‘Since the introduction of the CSL, the number of nurses, general practitioners, mechanical engineers and secondary school teachers increased by 50 per cent compared to the previous year’ (OECD 2010: 187).

Other OECD countries have introduced points systems for their permanent skilled migration programmes, similar to Australia and New Zealand, and they can now target occupations in which they have a shortage. This includes the United Kingdom (October 2008), Denmark (July 2008) and the Netherlands (January 2009) (OECD 2010: 58). In the United Kingdom, for example, the points-based system operates under ‘Tier 2’, for highly skilled workers who are on a shortage occupation list, are recruited after a resident labour market test or are intra-company transferees. Elsewhere, countries are implementing new policies to attract highly-qualified people or modifying existing policies. Japan, Malaysia, Singapore South Korea and Thailand are relatively new to identifying shortages and to using immigration as a means of increasing supply. They mostly admit health workers on temporary work visas, though Singapore is moving in the direction of more permanent migration for selected highly skilled workers.

In less developed countries, the issues have also been the focus of research and/or policy attention. The Philippines Department of Labor Report on the Problem of the Brain Drain in the Philippines, partly focusing on nurses, was produced in 1966. The ‘apparent validity of the concept [brain drain] was quickly recognised in health contexts elsewhere, from Latin America to India’ after this report was produced, according to Connell (2010: 43).3 India has a long history of medical migration and the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) estimated that 56 per cent of its medical graduates in the period 1956–1980 left the country (Khadria 2004: 35). Khadria argues that India is currently almost at the top of the list of countries as far as emigration of the ‘brain drain’ category of Human Resources for Science and Technology (HRST) is concerned and these movements include significant numbers of medical practitioners. Khadria (2006) has also examined current trends in nurse education and migration and has explored the possible consequences of these trends for stakeholders in India.

Other regions became increasingly concerned about the outflow of their health workers. Government officials and researchers in Africa (Osunkoya 1974), the Caribbean (Gish 1971), Latin America (Horn 1977) and Pacific states (Bartsch 1974) registered their concerns about ‘brain drain’ as early as the 1970s. Such concern has continued to be voiced by a growing number of researchers from these regions: for example, Nyonatar and Dovlo (2005) discuss Ghana in ‘The Health of the Nation and the Brain Drain in the Health Sector’. South Africa, Ghana and Nigeria were the major African sources in the 1970s but structural adjustment policies that were introduced in many Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries in the 1980s led to a drop in real wage levels (due to inflation) and salary compression (McCoy et al. 2008). The outcome was more rapid out-migration from SSA countries and movement towards a regional health workforce crisis. A recent paper by Clemens and Pettersson (2008) on African health professionals abroad provides valuable data which show that between 60 and 80 per cent of doctors born in Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, Angola, Liberia, Equatorial Guinea and Sao Tome and Principe were working abroad in 2000. Similar data are available for nurses.

Thomas-Hope (2002: 9) has consistently focused on this issue in relation to the Caribbean and has documented how the processes work, often in the absence of official data. Her 2002 report for the International Labour Organization (ILO) relied largely on newspaper articles and key informant interviews. Almost two-thirds of nurses trained in Jamaica from 1980 to 2000 emigrated, mainly to the United States, and few returned. Thomas-Hope (2002: 9) maintains that notices for teachers and nurses appear frequently in the Jamaican daily newspaper, as in the following case:

REGISTERED NURSES – FLORIDA U.S.

Salary from US$36k – $50k annum, no state taxes. Permanent visa processing at no cost for nurse who passes an interview with our Florida Hospital clients. … Call for schedule of local interviews soon (The Gleaner, November, 2000, 13F).

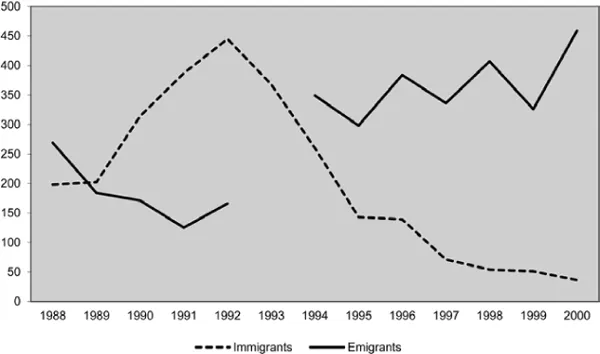

The absence of official or reliable data on the out-migration of health workers has been a considerable hindrance to researchers in less developed regions. It is one reason why country studies have been limited and the impact of the out-migration of health workers has gone relatively unreported in many areas. One possible exception is South Africa. The apartheid era in South Africa increased the exodus of mostly highly skilled South African workers (Mattes et al. 2000) and most emigrated to other countries of the Commonwealth where their health training was usually readily accepted. This trend continued and escalated from 1991, as shown in Figure 2.1. On the other hand, the immigration of health professionals fell sharply over this period.

Figure 2.1 Migration flows of health professionals in South Africa, 1988–2000 (official data)

Source: Adapted from Dumont and Meyer 2004

Unlike elsewhere in Africa, South Africa’s data collection systems have enabled this type of detailed analysis, though underestimation of emigration by a factor of three or four has been observed.4 The above data are broken down by occupation and the two major occupations are doctors and nurses, with the latter becoming by far the most important. Besides the availability of data, another important factor that has enabled such research to be conducted in South Africa was the establishment in 1996 of the Southern African Migration Project (SAMP), an international network of organizations.5 It has been conducting applied research on migration and development issues, as well as providing training and education, since that time. Its Migration Policy Series has included reports on Gender and the Brain Drain from South Africa (Dodson 2002) and The Brain Gain: Skilled Migrants and Immigration Policy in Post-apartheid South Africa (Mattes et al. 2000). Some of this research was commissioned by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and the European Commission (see Martineau and Martinez 1997, Martinez and Martineau 2002) thereby indicating their growing interest in the topic of mobile health workforces.6 Clearly, the availability of funds has been a major factor, as well as SAMP’s connection with Canadian academic colleagues in Ontario, in facilitating research.

The Regional Level

Interest in Europe in what is happening in Africa, especially South Africa, is manifested in the major piece of work from the OECD in its flagship publication on mobility, the 2003 Edition of Trends in International Migration. It included a chapter on the international mobility of health professionals, using South Africa as a case study. This chapter was the first attempt by a regional body to analyse the growing phenomenon of health worker mobility.

By the late 1990s, the OECD began collecting data from destination countries under its umbrella, and estimating the expatriate rate of doctors and nurses from various source countries to OECD countries. Obviously these data are limited as they exclude all non-OECD destinations. Nevertheless, the chapter on ‘Immigrant Health Workers in OECD Countries in the Broader Context of Highly Skilled Migration’ in the 2007 Edition of Trends in International Migration represents a breakthrough in terms of data collection and availability.7 The data show that in OECD countries in 2000, 18 per cent of employed doctors and 11 per cent of employed nurses were foreign-born. Nurses from the Philippines (110,000) and d...