![]() PART 1

PART 1

Reading the Instructive Language of the Body in the Middle Ages![]()

Chapter 1

Episcopal Anatomies of the Early Middle Ages

Lisi Oliver and Maria Mahoney

This chapter looks at physiological and metaphysical anatomies in episcopal writings from crucial periods in the development of Christianity in early medieval Europe through the works of two prominent bishops and scholars: St. Ambrose, whose scholarly and theological works spanned the transition from late antique to early medieval Europe; and Hrabanus Maurus, whose writings appeared several centuries later when Christianity was the generally accepted religion of western Europe. Thus these two bishops approach the body, physical and spiritual, from opposite directions which ultimately converge on the same truth:1 St. Ambrose, nurtured in the classical tradition and struggling to capture in human words the correct formulation of the Incarnation in the early years of the Church, provides a tangible and literal rhetoric of the body and its place in the supernatural, while Hrabanus Maurus, defending an already established Christian foundation and assimilating many different cultures, moves through the body to a more mystical and metaphysical plane. We begin by describing the approaches employed in St. Ambrose’s and Harbanus’ catalogues of human anatomy, addressing also the crucial transitional link provided by the Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. We then turn towards St. Ambrose’s and Hrabanus’ explications of divine and hagiographical bodies, and finally examine how their theologies of the human body are shaped by their response to the religious disputes current in their respective centuries.

The body is considered in its original perfection in all the episcopal writings, but St. Ambrose also considers the body in a disfigured state reflecting both the inward perfection of the martyrs and the sinfulness of their persecutors. In this paradigm, injury and disease are metaphors not for the sin of the afflicted person but rather the sins of others. The healthy body, on the other hand, is a fitting metaphor for the Godhead, even in its secondary representations whether written or painted, static or dynamic. A single rhetoric is not sufficient for the portrayal of the ultimate reality. The complementary approaches of St. Ambrose and Hrabanus Maurus towards rhetorical and metaphorical examinations of the human body—presented by two of the greatest religious scholars of the early Middle Ages—provide a foundation from which to move to more specialized discussions of approaches towards the body in times both of disease and of health.

Human Anatomy in Early Medieval Episcopal Writings

The first of the early medieval anatomies is grounded in the Christianity of the late Empire. St. Ambrose was elected Bishop of Milan in 374, at which point he was baptized (previously he had only been a catechumen) and ordained. In the last week of Lent, probably in 389 AD, St. Ambrose preached nine addresses on the six days of Creation, which were subsequently committed to writing. Much of St. Ambrose’s text on the Hexaemeron followed a similar set of sermons preached by his friend and Greek contemporary St. Basil. Both preachers include in their texts a sentiment traceable to Aristotle and later repeated by Isidore (quoted here from St. Basil): ‘What is the form of quadrupeds? Their head is bent toward the earth and looks towards their belly, and only pursues their belly’s good. Thy head, O man! is turned towards heaven, thy eyes look up.’2 This sentiment pervades the description of the body which St. Ambrose adds to the material he has drawn from Basil.3 Chapter IX of his Hexaemeron begins by declaring the purpose for this addition:

But now of that same body of man some other things should be said also, for who denies it to be more outstanding in gracefulness and dignity than the rest? For even if the substance seems to be one and the same for all earthly creatures, strength and height is greater in certain beasts; however, the form of the human body is more lovely, the posture erect and tall, so that there is neither an extreme height nor a vile and lowly littleness; thus the physical appearance itself of the body is sweet and pleasing so that there is neither a bestial enormity as for a monster, nor a lean thinness as for a sick person.4

Two-thirds of the subsequent anatomical description is taken up by facets of the head, which

has a position above the other members of our body. In the same way, the sky stands supreme among the other elements, just as a citadel amid the other outposts in a city’s defense. In this citadel dwells what might be called regal Wisdom, as stated in the words of the Prophet: ‘The eyes of a wise man are in his head.’ That is to say, this position is better protected than the others and from it strength and prevision are brought to bear on all the rest.5

This citation demonstrates two typical facets of St. Ambrose’s anatomy. First, scriptural reference is used descriptively rather than allegorically. Second, particularly in reference to the head, martial imagery abounds. The head itself is like a ‘commander-in-chief’ (speciosa caesaries); the eyes are “sentries” (vigilantes) placed against “the approach of hostile bands” (adventientum catervarum hostilium) “with courage” (fortitudo). In the middle of the eyes are the pupils,

… which perform the service of seeing. These are fortified by adjoining hairs just as by a kind of wall in a circuit, lest they should be harmed by any offense of inflicted injury. Whence the Prophet says, demanding for himself secure help: Guard me, Lord, as the pupil of the eye (Psal. XVI, 8); so that he would have the solicitous and safe guard of divine protection as it is deemed worthy to protect the eye by this certain and safest wall of nature.6

The eyebrows form “defenses” (munimenta) for the eyes, protecting (protegente) as “in a citadel” (in arce), from which they can “defend themselves from all, even the slightest attacking force” (ab omnia vel minima offensione defendi)—such as specks of dust or dirt, drops of rain, or rivulets of sweat. The nose (=nostrils) offers “a covering for the interior position” (interiorem partem sepiant); the cheeks provide “a protecting embankment” (exiguum muntiones); the ears provide a “bulwark” (propugnacula) against the penetration of heat and cold; the mouth, containing its “rampart of teeth” (dentium vallum), “furnishes strength” (vires muniat) to the other organs; and the forehead and jaw serve “to provide all with a wall of protection” (omnia circumvallare).

St. Ambrose (following Galen and other early Greek anatomists) identifies the brain as the center of the senses; once he has completed the description of the head that houses it, he makes the somewhat premature statement that “we have now completed our general description of the human body.”7 Only the hand, with which we variously feed ourselves, bring sacrifices to the altar, dispense the divine mysteries, and defend our physical beings, elicits any detailed attention.8 The military metaphors continue, however: “The hand is the outpost of the entire body, as well as the defender of the head” (Manus est totius corporis propugnaculum, capitis defensatrix); the hands are enjoined to “military service” (militae munius); and “disciplinary orders” (impositae disciplinae) are set for the stomach.9

The description of the torso begins by comparing the body to Noah’s ark: the ribs contain and protect the internal organs. But at this point, St. Ambrose is content to peer down from the deck rather than descend into the bilge. The final third of his discussion on anatomy sketches the rest of the external body as well as the internal organs, concentrating primarily on location.10

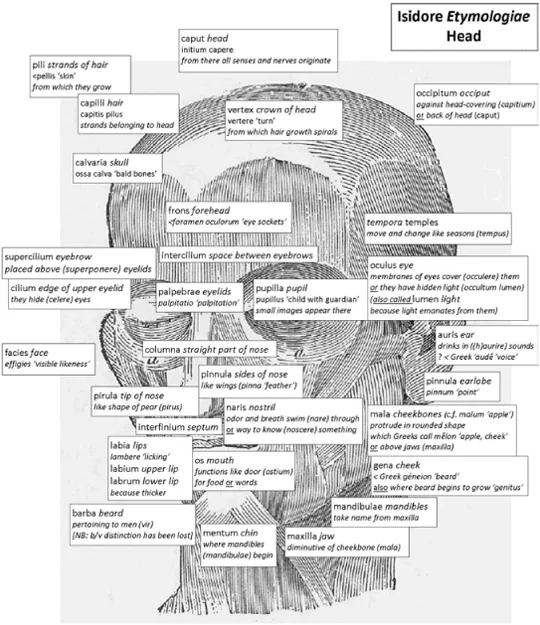

A very different approach to the human body was taken by St. Isidore, the most famous of the medieval anatomists.11 He was born around 560 in Cartagena, but after the Byzantine invasion in 557, his family moved to Seville. Around 600, St. Isidore succeeded his brother Leander as Bishop of Seville. His last—unfinished at his death—and arguably most influential work was the Etymologies; Book 11 contains a thorough examination of human anatomy and provided the model for many later scholars, including Hrabanus Maurus. Exemplifying his approach, the chart in Figure 1.1 presents St. Isidore’s breakdown of the human head.12

St. Isidore’s primary focus is on how physiological function determines the nomenclature of body parts. He presents various types of etymology, some real and some fanciful. In the former category, we can place the association of facies “face” with effigies “physical likeness,” or the alternative associations of occipitum “occiput” with caput “head” or (with a similar derivation) capitum “head-covering.” In the latter category, St. Isidore errs in deriving oculus “eye” from occulere “to cover” because eyes are covered by their lids, which also hide their light—in fact, the term is a direct inheritance from Proto-Indo-European *okw- “see, eye.” Even more fanciful is St. Isidore’s etymology of naris “nostril” from the fact that odor and breath nare “swim” through them or—even further afield—that they permit us noscere “to know” things. The term naris is inherited from Proto-Indo-European *nas- “nose.”13 The study of Indo-European linguistics was not inaugurated until the end of the eighteenth century; St. Isidore, however, anticipated the endeavor by reaching for etymological explanations within the intellectual realm of his time. His solutions thus often fall within the area of folk etymology, assuming that words that sound alike can also have an etymological relationship. St. Isidore also often supposes, wrongly, that when an etymologically-related term exists in Greek, the Latin term is derived from the Greek, as in Latin ped “foot” alongside Greek pod; both terms are actually independently derived from a common source.14 Finally, St. Isidore occasionally refers to physical placement as a reason for naming: the posteriora (“hindparts”) are at the back of the body so that sight will not be defiled by watching excrement passing; the same is true of the meatus (“lower channel”). This explanation seems to echo St. Ambrose’s declaration of the perfection of the human form: all is arranged to be both proper and pleasing.15

Fig. 1.1 St. Isidore’s breakdown of the human head.

While St. Ambrose concentrates on the perfection of the human form, St. Isidore concludes Book XI.i by enumerating various anatomical rationales:

Some of the parts of our body were created solely for reasons of usefulness, as for instance the viscera; some for usefulness and ornament, like the sense organs in the face, and the hands and feet in the body, limbs that are both of great usefulness and most pleasing form. Some are purely for ornament, as for instance breasts in men, and the navel in both sexes. Some are there to allow us to tell the difference between the sexes, as for instance the genitals, the grown beard, and the wide chest in men; in women the smooth cheeks and the narrow chest; although in order to conceive and carry a fetus they have wide loins and sides. That which pertains to human beings has been partly treated.16

Although St. Isidore considered this only a partial treatment, it is by far the most complete analysis of the human...