The Body in Culture

The medical treatises published in late sixteenth-century France and Switzerland offer a clear indication of the significant shift being prepared in the medical profession from reliance on classical sources to more empirical methods of inquiry; those treatises on sex, sexuality, and childbearing show that these shifts are significant for the early modern elaboration of sexual difference and of gender roles. Publishing in France was dominated by the faculty of theology at the Sorbonne, the prime censoring body in this period, which also dictated the teaching of medicine, as the faculty of medicine was subordinated to the faculty of theology. The Sorbonne vehemently, and sometimes violently, advocated Aristotelian and Thomistic thought over any other. But, by the end of the sixteenth century, the control the Sorbonne wielded was slipping: a number of influential surgeons such as Ambroise Paré and Jacques Duval published treatises that either subtly or openly called into question its conservative approaches. More progressive universities such as Basel and Montpellier supported faculty (Caspar Bauhin at Basel) and produced students (François Rabelais) who published innovative works on sex and sexuality. The following chapters, on medical treatises in Continental Europe, will trace this shift from scholastic and rigidly categorical discussions of sex to more skeptical and flexible presentations of sexual difference.

As Thomas Laqueur demonstrates in his book Making Sex,1 the Renaissance was at first still dominated by dualistic, primarily Aristotelian, notions of sex and of generation, privileging the male as the superior, that is to say active, force in reproduction. A significant movement away from these notions can be traced towards the end of the century, one that, as Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park have demonstrated, is linked to the revival of Hippocratic medicine in the second half of the sixteenth century.2 Furthermore, alternatives to this simply dualistic worldview already existed in alchemical treatises of the time, and in other forms of mystical thought. In many alchemical treatises, the body is seen as part of a larger (in fact, potentially infinite) whole that is represented as the Divine. One can see in this view of the relationship between macrocosm (the Divine) and microcosm (often portrayed as human) the origins of Spinoza’s notion of “an absolute and infinite substance” (as summarized here by Elizabeth Grosz):

Substance has potentially infinite attributes to express its nature. Each attribute adequately expresses substance insofar as it is infinite (the infinity of space, for example, expresses the attribute of extension), yet each attribute is also inadequate or incomplete insofar as it expresses substance only in one form. Extension and thought – body and mind – are two such attributes. Thus, whereas Descartes claims two irreducibly different and incompatible substances, for Spinoza these attributes are merely different aspects of one and the same substance, inseparable from each other. Infinite substance – God – is as readily expressed in extension as in thought and is as corporeal as it is mental.3

The body, then, cannot be contained by the conceptual structures that privilege the mind; as with any entity,

… The forms of determinateness, temporal and historical continuity, and the relations a thing has with coexisting things provide the entity with its identity. Its unity is not a function of its machinic operations as a closed system (i.e., its functional integration) but arises from a sustained sequence of states in a unified plurality (i.e., it has formal rather than substantive integrity). (Grosz, Volatile Bodies, p. 12)

As Moira Gatens notes, the Spinozist body is “a productive and creative body which cannot be definitely ‘known’ since it is not identical with itself across time.”4 Similarly, in many alchemical treatises, the body is seen as dissolving and reconfiguring its own boundaries.

By the end of the sixteenth century, influential medical authors recognize the intractability of the body in the face of dualistic legal, theological, and philosophical discourses. Theoretical discussions of hermaphrodism focus on the imagined monstrosity, easily contained within a dualistic mode of thought, because it does not in fact exist (or is at least believed by the very authors who describe it not to exist). The “biological” hermaphrodite, on the other hand, can only be defined by a legal determination of its status or by extreme medical intervention (usually deadly in the early modern period), but can never be adequately described, since, in the early modern scheme of things, the hermaphroditic body is never identical with itself even in a specific time frame.

Thus, the evolution of theories of sex and sexuality is linked to the figure of the hermaphrodite, particularly in the works of Paré,5 Bauhin, and Duval. Duval and Bauhin use the figure of the hermaphrodite to reveal the significant differences between male and female, rather than arguing for one sex (male). Although they still repeat some Aristotelian notions about the superiority of the male (more so Duval than Bauhin) and although the innovations in these works remain unfulfilled until much later (Laqueur would argue that the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries form the period of real change in general attitudes towards sex or gender),6 they re-open the question of sex and sexuality in significant ways, and help to shake the stranglehold of Aristotelian theories of generation. Thus, we will read these three works as precursors to an important shift in the representation of sexual difference in medical texts.

This shift in the representation of sex and sexuality is accompanied by a shift in the modes of scientific discourse. In the works of Bauhin in particular, a tension between theoretical explanations and actual case studies becomes quite evident. The theory, stemming from Aristotelian and Hippocratic philosophical medicine, cannot be reconciled with empirical evidence. While the importance of empirical data is increasingly recognized in the late sixteenth century, the sheer force of the humanist revival of classical sources carries the authority of Aristotle and Hippocrates well into the seventeenth century, thus maintaining this uneasy contradictory coexistence of outdated theory and contemporary observation. The inhuman hermaphrodite, such as the monster of Ravenna, being almost totally inscrutable, is more easily placed within a theoretical framework; that is to say, a reading can be imposed on a figure which is not remotely human. But a human hermaphrodite with no other “monstrous” characteristics, such as Marie-Germain (although she is more a transsexual than a hermaphrodite), seems to jar with longstanding constructs of gender (as the social or imaginary manifestation of sex), as we shall see. This tension is evident in Paré’s Des monstres, in the juxtaposition of the Marie-Germain story with the chapter on hermaphrodites. It is even more apparent in Bauhin’s repeated attempts to theorize about the cause and nature of hermaphrodites while drawing from real case studies that defy any coherent explanation. Jacques Duval manages to crystallize case studies within clear rules of sex distinction, returning to essentially Aristotelian models; his work signals the return in the seventeenth century to orderly and hierarchical notions of gender, at least in the medical profession. Nonetheless, some of the cases he cites reveal the gap between cultural notions of gender, and actual manifestations of ambiguous sex. In this contention, I might seem to be contradicting an argument made by Daston and Park that what postmodern theorists now deem “cultural” rather than natural was not so clearly distinguished in the early modern period. Indeed, distinctions between natural and cultural were not so clear in the legal or medical works of the time, and the revival of the work of Sextus Empiricus, and particularly of his accounts of cultural relativism in The Outlines of Pyrrhonism, problematized the acceptance of “active” and “passive” sexual roles as natural categories. Duval’s insistence on the importance of language for the designation of gender, and his retreats at crucial moments into mythological or literary examples, underscores the problematic relationship between theories of sex inherited from classical philosophy and the empirical evidence the dual-sexed body offers to the contrary. Clearly, the imaginatively created or the far-distant monstrous hermaphrodite serves as a better example for proponents of Aristotelian models, since it is in essence a blank sheet on which anything can be written. But the blankness of the monstrous hermaphrodite, the possibility it offers for manipulation of the body into any form, put into question any of those theories which might depend upon it. Thus, the monstrous hermaphrodite is at once fundamental to established theories of sexual difference and destructive of them, showing them as purely imaginary constructs that create their own evidence in circular fashion.

The Monster of Ravenna

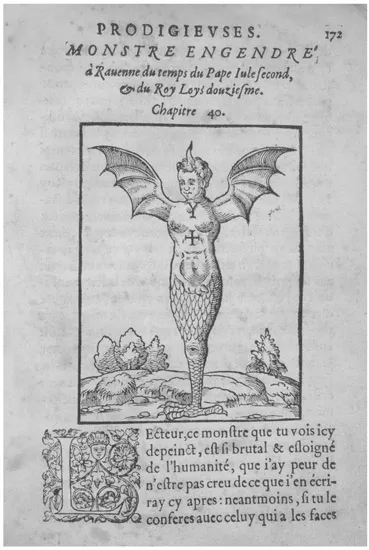

Ravenna, 1512. A hermaphroditic monster is born, which, due to its mixture of sex and species, remains indecipherable. Because it does not fit into neat categories of male or female, man or animal, it must be made to conform to some type. Thus, the monstrous form becomes a blank page onto which a highly politicized text is inscribed. In fact, this monster has an illustrious and long iconographic genealogy, traced by Ottavia Niccoli in her book People and Prophecy in Renaissance Italy.7 It also metamorphoses, from a two-legged creature to a monopede, from bearing the letters YXV to simply a Y and a cross, from bat-wings to bird-wings, from no sexual characteristics to hyper-masculine to hermaphroditic, as these various forms suit the interpretations placed upon them. Niccoli points out that these readings are politicized from the first manifestations of the creature; first clerical abuse is suggestion, then the corruption of the Papal Court (People and Prophecy, pp. 46–51). Nearly a half-century later, Pierre Boaistuau, author of the Histoires prodigieuses, offers a version of this text. Boaistuau seems particularly concerned with monsters and with monstrous births, and clearly places hermaphrodites in this category (as does Tesserant, who augments his collection of tales). His story of the hermaphroditic monster of Ravenna is taken from Rueff’s version of the story; he also credits Lycosthenes, Multivallis,8 and Hedio, and

Figure 1.1 Monster of Ravenna, from Pierre Boaistuau and Claude de Tesserant, Quatorze histoires prodigieuses, adioustées aux precedents … (Paris: Jean de Bordeaux, 1567). Courtesy of the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

the interpretation of the monster is virtually identical to that of Multivallis, with the negative references excised. This monster seems to represent a fear of the confusion between human and animal, as well as between male and female. This confusion is represented as a threat to political and authorial authority: “Lecteur, ce monstre que tu vois icy depeinct, est si brutal & esloigné de l’humanité, que i’ay peur de n’estre pas creu de ce que i’en écriray cy apres …” (“Reader, the monster which you see pictured here, is so brutal and distant from humanity, that I am afraid of not being believed when I write what I am about to write”).9 Rather than offering a scientific explanation alleging the problems and risks of generation, as he does in other stories, Boaistuau offers the usual allegorical reading of the creature:

… il fut engendré à Ravenne mesme (qui est l’une des plus anciennes citez d’Italie) un monstre ayant une corne en la teste, deux aesles & un pied semblable à celuy d’un oyseau ravissant & avec un oeil au genoil, il estoit double quant aux sexe, participant de l’homme et de la femme, il avoit en l’estomac la figure d’un ypsilon, & la figure d’une croix, & si n’avoit aucuns bras … par la corne estoit figuré l’orgueil & l’ambition: par les aesles, la legereté & inconstance: par le default des bras, le deffault des bonnes oeuvres: par le pied ravissant, rapine usure & avarice: par l’oeil qui estoit au genoil, l’affection des choses terrestres: par les deux sexes, la Sodomie: & que pour tous ces pechez qui regnoient de ce temps en Italie, elle estoit ainsi affligée de guerres: mais quant à l’Ypsilon & à la Croix, c’estoient deux signes salutaires: car l’Ypsilon signifioit vertu, & puis la Croix, qui denotoit que s’ilz vouloyent se convertir à Iesus Christ, & songer à sa Croix, c’estoit le vray remede. (Boaistuau, Histoires prodigieuses, pp. 172–3)10

(… there was born at Ravenna itself (which is one of the most ancient cities in Italy), a monster with a horn on its head, two wings, and one foot similar to that of a bird of prey, and one eye on its knee, double as to its sex, participating in both male and female natures, it had on its stomach the sign of a Y and the sign of a cross, and yet it had no arms … the horn was the symbol of pride and ambition: the wings, lightness and inconstancy: the lack of arms, the lack of good works: by the raptor’s foot, pillage, usury, and avarice: by the eye that was on the knee, the attraction to earthly matters: by the two sexes, Sodomy: and that because of all of these sins that reigned at this time in Italy, this country was thus afflicted by wars. But as for the Y and the Cross, those were two signs of salvation: because the Y signified virtue, and then the Cross, which conveyed that if they would convert to the laws of Jesus Christ, and think of his Cross, that was the true remedy …).

The moral message that Boaistuau inscribes into his reading of this body is quite clear. It should be remembered that, even through the Renaissance, the term sodomy was used to designate a wide range of behaviors considered to be vices, from male homosexuality to bloodshed.11 The Y and the cross symbolize potential salvation through repentance. The whole “text” is a critique of Julius II and his corrupt circle (as it is in Paré’s treatise, Des monstres). This monster cannot merely be described, it must be read, and to a large extent, the reading creates the monster. A “normal” body would s...