![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Rolf Loeber, Machteld Hoeve, N. Wim Slot and Peter H. van der Laan

Juvenile delinquency is a vexing problem across countries in Europe (ESB, 2010), and is one of the major causes of physical harm and property loss inflicted on victims. Countries differ in major ways in the manner in which they deal with juvenile delinquents inside and outside the juvenile court and, sometimes, the adult court systems. Countries also differ in their legal definitions of the age of criminal responsibility (ranging from 8 to 18) or the youngest age at which adult criminal law can be applied to juveniles (ranging from 15–18) (see Killias, Redondo and Sarnecki, this volume).

Scholars, professionals and lay people regularly debate what causes young people to commit crimes. Some argue that there are ‘bad’ individuals who from childhood are already out of control, many of whom become life-course-persistent delinquents. Others argue that juvenile delinquents are to a high degree a product of their environment: the worse the environment, the worse their behaviour over time. In this volume we present evidence that both positions are tenable, but we also provide proof that many juvenile delinquents tend to stop offending in late adolescence and early adulthood.

Since in most countries in Europe as well as in the US the legal transition between adolescence and adulthood takes place at age 18, another point of discussion is whether young people by age 18 have full control over their behaviour and whether their brain maturation is complete at that age. If so, does this mean that from age 18 onwards we can attribute the causes of offending and culpability to persisting individual difference factors rather than mental immaturity and disadvantages in families, schools, and social environment?

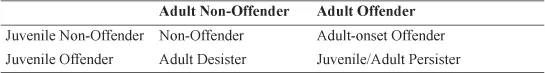

This volume focuses on the age period between mid-adolescence and early adulthood (roughly ages 15–29)1 and it addresses what we know about individual differences among offenders in their persistence compared to desistance from offending. The volume draws on studies in North America and Europe (see Killias et al., this volume). Figure 1.1 summarizes the four key groups we are interested in: juvenile/adult persisters whose offending continues from adolescence to early adulthood (and perhaps later); early adult desisters who were juvenile offenders who desist during adolescence and do not continue to offend into early adulthood; adult-onset offenders who did not offend during adolescence but who become offenders during early adulthood; and, lastly, non-offenders, who do not offend either in adolescence or early adulthood. We shall examine the four groups in general population samples, but we shall also focus on sex offenders (see Bijleveld, Van der Geest and Hendriks, this volume).

Figure 1.1 Offending in the juvenile and early adult years

Maturation

In general, childhood is seen as a period in which children have not yet fully developed self-control, and impulsivity tends to lead to misbehaviour and acts of delinquency (Jolliffe and Farrington, 2009; Moffitt, 1993). This is why during the period from childhood into adolescence parents, teachers and other adults help to modulate children’s poor internal controls, teach them skills to navigate problems in life, and help them avoid inflicting harm on others. Thus the years across childhood and adolescence are seen as a pivotal period in which to bring about in young people a shift from external to internal controls. However, the appearance of physical maturity in late adolescence and early adulthood does not necessarily mean that mental maturity has been fully achieved and that internal controls are completely formed and are regularly exercised by the young person (see, for example, Steinberg et al., 2009; but see critique by Fischer, Stein and Heikkinen, 2009).2

The presence of internal controls can be expressed in a number of complementary ways:

• Improved decision making vs letting things happen.

• Improved perception of the future consequences of actions.

• Avoidance of self-harm.

• Increased self-regulation.

• Decreased sensation seeking.

• Decreased impulsiveness.

• Decreased risk taking.

• Improved emotional control.

• Decreased susceptibility to peer influences.

Control in one area does not mean necessarily that control in another area is also in place. However, there is a lack of agreement among scholars regarding the age at which psychosocial maturity and general cognitive capacity reach their maximum values (Steinberg et al., 2009; Fischer, Stein and Heikkinen, 2009). There are major individual differences in the gradual mastering of internal controls, with some youth maturing early in this respect, and others in more vulnerable populations (see Bijleveld et al., Chapter 5, this volume, and also Overview, this volume) taking a much longer time (see below). Contrary to legal assumptions, age 18 is not a fixed date of completion of this process for all young people.

While all young persons go through the transition between adolescence and adulthood, scholars disagree about whether an in-between stage of ‘emerging adulthood’ is a separate stage of development, prompted in part by demographic delays in industrial societies over the past decades in the timing of marriage and parenthood (Arnett, 2000). There is some agreement that in recent years ‘the transition to adulthood has become increasingly prolonged with more youth staying in education longer, marrying later, and having their first child later than in the past’ (Hendry and Kloep, 2007, p. 74) and that this applies to a number of industrialized countries (see Blokland and Palmen, this volume; Fussell and Furstenberg, 2005). Masten et al. (2004) characterized the transition period between adolescence and early adulthood as a window of opportunity to change the life course in terms of individuals having second-chance opportunities and turning points in their lives. Other scholars, however, see the transition period as an instance of delayed adulthood accompanied by delayed outgrowing of adolescent behaviours.

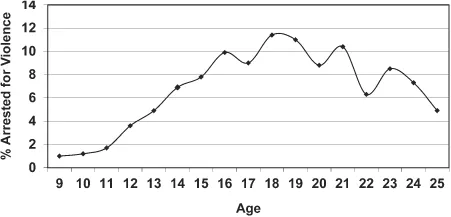

The Age–Crime Curve

Research findings agree that the prevalence of offending increases from late childhood to adolescence, peaks in late adolescence, and decreases subsequently to adulthood. This is generally known as the age–crime curve (Farrington, 1986; Tremblay and Nagin, 2005; Laub and Sampson, 2003). An example of such a curve is shown in Figure 1.2. The curve can be observed in all populations of youth. Less well known is the fact that, although an early – compared to a later – age of onset of offending is associated with a longer criminal career, the highest concentration of desistance takes place during late adolescence and early adulthood irrespective of age of onset, which corresponds with the down-slope of the age–crime curve (see Overview, this volume). In fact the decrease in prevalence in the down-slope of the age–crime curve is very substantial, in some datasets from about 50 per cent to about 10 per cent of all persons (for example, Loeber et al., 2008).

Figure 1.2 An example of an age–crime curve (Loeber and Stallings, 2011)

All available research on age–crime curves shows that the legal age of adulthood at 18 has no significant relevance and is not accompanied by a sharp change (or decrease) in offending at exactly that age. Serious offences (such as rape, robbery, homicide and fraud) tend to occur after the emergence of less serious offences in the late adolescence/early adulthood window. Even for serious offences, however, there is no clear dividing line at age 18. Steinberg et al. (2009) conclude, ‘The notion that a single line can be drawn between adolescence and adulthood for different purposes under the law is at odds with developmental science’ (p. 583).

Offending Careers

This volume addresses what we know about individuals’ persistence in contrast to desistance from offending (see Figure 1.1). The main focus is on serious offending careers (for example, violence, drug dealing and sexual crimes), which for a substantial number of offenders extend beyond age 18 into adulthood and for other offenders cease after adolescence (see Blokland and Palmen, Chapter 2, this volume; Piquero, Hawkins and Kazemian, 2012). Blokland and Palmen address the following key questions about delinquency careers: How common is persistence in and desistance from offending between adolescence and early adulthood? How common is the onset of offending during early adulthood? The criminal career parameters that are reviewed in Chapter 2 are prevalence and frequency, continuity, escalation and specialization, types of crimes and criminal careers, co-offending, prediction of offending into adulthood, and prediction of onset of offending in the young adult years. In addition, we focus on certain categories of offenders (drug dealers, gang members, homicide offenders and sex offenders) and ask whether – compared to other offenders – they are more likely to persist in offending into adulthood (see Overview, Chapter 12, this volume).

The Search for Causes

As mentioned, the down-slope of the age–crime curve represents a very substantial decrease in the number of offenders from the peak of the curve in middle to late adolescence.3

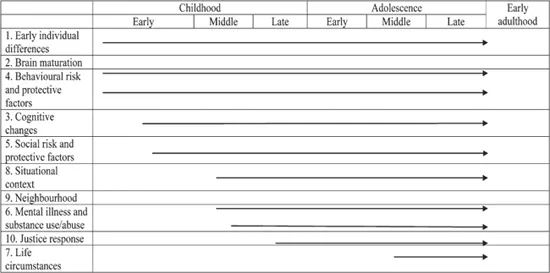

Causes (here called explanations) of persistence in and desistance from offending are reviewed in Chapters 3, 4, 5, 11 and 12. These chapters also focus on explanations for the shape of the age–crime curves in different populations. We consider the following ten explanatory processes:

1. Early individual differences in self-control.

2. Brain maturation.

3. Cognitive changes (for example, decision making to change behaviour).

4. Behavioural risk factors (disruptive behaviour and delinquency) and behavioural protective factors (nervousness and social isolation).

5. Social risk and protective factors (family, peers, school).

6. Mental illnesses and substance use/abuse.

7. Life circumstances, such as getting married, becoming employed, moving to another neighbourhood.

8. Situational context of specific criminal events, including crime places and routine activities.

9. Neighbourhood (for example, living in a disadvantaged neighbourhood, and the concentration of impulsive and delinquent individuals in disadvantaged neighbourhoods).

10. Justice response (for example, transfer to adult court, longer sentences).

We address the following questions: (a) Does each process explain persistence in offending from adolescence to early adulthood? (b) Does each process also explain desistance during that period? (c) Does each process explain the onset of offending during early adulthood? The explanatory processes tend to operate at different ages of juveniles, some early and some later in offending careers, which is shown in Figure 1.3

Justice Response

Justice response to law breaking by young people is specified in part in countries’ criminal codes but partly depends on how that code is interpreted and how much discretion is given to the police, judges, prosecutors, and other justice personnel. The justice response is also much influenced by legislators at the local and national government level who, rightly or wrongly, call for harsher and longer sentences to be applied to young offenders, in particular for those older than 15.

Figure 1.3 Approximate temporal ordering of explanatory processes investigated for persistence in, desistance from, and adult-onset of offending

Over recent decades, discussions in the Netherlands have focused on whether or not to adjust lower and upper age limits for penal procedures. From a variety of perspectives it has been proposed to implement separate or amended sanctions and procedures for young adults. In this regard, the main question here addressed by Liefaard (Chapter 7, this volume), Van der Laan et al. (Chapter 8, this volume), and in the Overview (Chapter 12, this volume) is: How well does persistence in and desistance from offending during the transition between adolescence and adulthood map onto the minimum legal age of adulthood (i.e., age 18 in most countries)?

As mentioned, there are many explanations for persistence in and desistance from offending between adolescence and early adulthood, and for young adult onset of offending. These explanations are relevant to legislation and to the administration of juvenile and adult justice. In Chapters 7 and 8 we address the following points: What are the legal implications of knowledge of explanatory processes from adolescence to adulthood? Are legal boundaries related to young people’s maturation and development of cognitive control (or lowered impulsivity)? Does the legal system improve young people’s cognitive control or are the juvenile and adult justice systems impervious to young people’s cognitive development?

Several other key questions are relevant for legislative consideration: What is the usefulness of legislation stipulating minimum or longer sentences for offences for young offenders? Would lowering the age of adulthood, for example to age 16, decrease you...