![]()

1

Exordium

We are living in a time of increased secularism in the West. Christianity is on the decline, and while some other spiritualisms and religions, notably Islam, gain in popularity, an ever increasing number of people identify themselves as agnostics and atheists.1 However, the legacy of Christianity is all around us, and indeed within us, not least in the form of ecclesiastical buildings, from little country churches to the great medieval cathedrals and basilicas of Europe. What is to become of all this ecclesiastical architecture as congregations shrink and the cost of upkeep rises? These types of buildings have of course been threatened by changing ideologies before. Notre Dame de Paris was famously almost pulled down by the secularist zealots of the French Revolution and similar fates have befallen Orthodox churches and Buddhist temples as a result of the anti-religious policies of secular Communism in the former Soviet Union and China respectively.

Assuming that Christian religious services won’t be held much longer in many of our churches, I ask myself: are these buildings worth preserving beyond the Christian era? If they are, what is it in particular about them that we value? The architecture? The history? Or is their value wholly or at least partially attached to the particular rites and performances that take place in them, rendering them into largely meaningless albeit attractive shells once the use for which they were built and intended ceases to apply?

I am one among the hordes of pilgrims who like few things better than a spot of church crawling, be it in Rome or some remote corner of northern Europe. As a thoroughly-lapsed Christian, my pilgrimages are not religious, but rather cultural and art historical. And yet, while visits to other cultural heritage and art historical sites can prove eminently gratifying each in its own way, an old church, even when not particularly distinguished in its architecture or history, will stand apart as a peculiarly irreplaceable sort of space for me. As I have found myself standing, hushed, alone or with one other, in the westernmost part of a nave, ready to once again undertake the peregrination through that pregnant space, I have had cause to wonder why it is that a church can hold such fascination for me and others like me. As this question has nudged at me for some time now I have decided to undertake an exploration of what it is about sacred architecture, even in this unprecedentedly secular age, that continues to exercise enchantment on so many of us, believers or not.

Churches are usually open, usually free, and provide refuge from sun and heat – or rain and snow – on any given day. They are quiet and little is expected of one in them. You can sit, stand or walk around in them as you see fit. They are not seldom architecturally arresting, besides which they may contain works of art, candles and lamps, reliquaries, effigies, tombs and plaques. There is much to see and ponder on a walkabout. While libraries and art galleries can offer some of the same opportunities for a relaxed, quiet amble through the stacks or collections, there is invariably a certain something which they lack in comparison with churches. Perhaps it is that they seem to want to reach through to our souls via our minds, whereas a church also seems to suggest the possibility of conversing with our souls through our senses or, as it were, directly.

Perhaps the greater part of the attraction lies in their otherness – in their province of acting as rabbit holes, as escapes from an otherwise ubiquitously mundane reality, to something simultaneously more liberating and more serious, because I do believe people need counterpoints in life in order to experience a sense of satisfaction, equilibrium and emotional sustainability, perhaps even meaning. Our very bodies require periods of work to be followed by periods of rest. It seems obvious and perhaps not worth mentioning, but in the light of recent revelations of a growing cult of work, and of the results of capitalism’s endless striving for the bigger gain and the competitive edge,2 merciless if unchecked, it is worth reflecting on the value of concepts such as the sabbath, which recognised a living body’s need for rest, a living mind’s need for reflection. This weekly rhythm between work and rest is echoed in the annual rhythms that festivals and other rituals traditionally give our collective lives. We mark holidays from every-days, ordinary time from extraordinary, as the Catholics have it, and keep and honour critical occasions in the cycle of life, notably events surrounding births and deaths. These observances of the ebb and flow of being is of course not specific to Christianity, nor even to religion more generally, if we limit our understanding of the word to the institutionalisation of the human propensity to ponder the metaphysical, but is observable in supposedly secular societies as well as in states of nature. The commercial version of Christmas and the decorations of lawns and porches with inflatable witches and goblins at Halloween are no less an expression of the need to distinguish and mark the various times of the year than are religious calendar events – if indeed, it must be said, the former can boast somewhat less of a claim to a satisfying address of the presage and longings that spring from the anticipation of our common moribund fate.

The counterpoint between sacred and profane time knows a corresponding architectural parallel in some cities to this day, offering a pleasing visual rhythm between church steeples, domes and campaniles on the one hand, and the lower, less pointed roofs of the profane buildings around them on the other. It has always to me seemed somewhat of an expiation of humanity’s otherwise rather shocking proclivity towards everything that is narrow and shallow that the highest building effort, the most expensive and the most risky, was reserved for the structure that emblematised our search for meaning, our reaching out to beginning and end, to the edge of our knowing, an acknowledgement of our temporal minuteness and, thrillingly, a simultaneous imagining of something altogether other in which we could yet play a part.

Obviously the reality of much ecclesiasticism, of its judgements and anachronisms, its money games and power games, is far from the idealistic vision of how faith could and should be represented. Those compound failures be what they may, however, the principle remains that society did not until very recently see fit to raise any other structures – those dealing more transparently with the here and now – to equivalently conspicuous heights. Moneylenders and usurers did their trade in the dark; gamblers resorted to trying their luck in semi-dereliction – how people with these particular preoccupations have risen in the world since, now that financial institutions, insurance brokers and casinos occupy the tallest and glitziest towers in many of our contemporary city centres. One does perhaps not need to be a would-be contemplative to feel, like Hamlet, that ‘time is out of joint’. This book may be read as my attempt, however modest and however futile, not quite ‘to set it right’ perhaps, but certainly to present an alternative prospect: that of giving more serious consideration to the buildings that stand as architectural expressions of humanity’s most elevated and profound inclinations.3

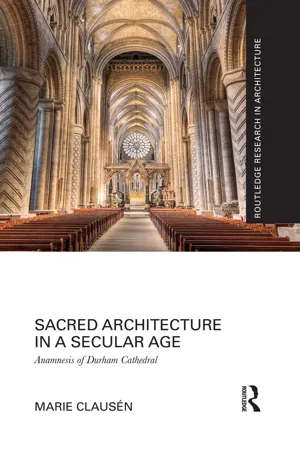

As Christian congregations continue to shrink throughout much of the Western world, and the church itself no longer enjoys a self-evident role as an institution of philosophical, political or economic puissance in our societies, the fate of a number of church buildings becomes increasingly precarious. Some are simply torn down as numbers of worshippers dwindle and pews stand empty. Those that have been left standing, desacralised, have in some cases been found new life in a range of functions, some perhaps more fitting than others. Examples of new uses that can be said to have brought new relevance and resonance to former churches are transformations into multifaith and conflict resolution centres, venues for musical and theatrical performances, art galleries or bookshops (Figure 1.1).4 These types of new uses appear to feed off the various traditions kept by the church. The arts have for a long time been affiliated with religion and churches: lime paintings, reredos and altar paintings, holy roods, and sculptures of the Virgin and Child all represent artistic impulses gratified within the framework of the church, so the step to functioning as an exhibition space for visual arts is not necessarily a long one. Similarly, music has long been an integral part of church services and song a very old way to communicate (with) the divine. Phenomena such as sacred dance have also made their way back into mainstream church practice, having been marginalised as an expression of new age spiritualism until fairly recently, but of course having its foundation already in primitive cult practices. And the link between books and religion is of course obvious, with the three world religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam collectively known as religions of the book, not to mention the role monasteries played for hundreds of years in European book production.

Figure 1.1 Bookshop Polare Dominikanerkerkstraat in Maastricht (photograph: FaceMe PLS (Peter Dewit); licence: CC A 2.0 Generic).

Other perhaps less seemly new uses to which church buildings have been put, or shall we say uses that at any rate do not follow naturally from any of the traditional preoccupations of churches, include luxury condominiums, bank and insurance offices, bars and nightclubs.

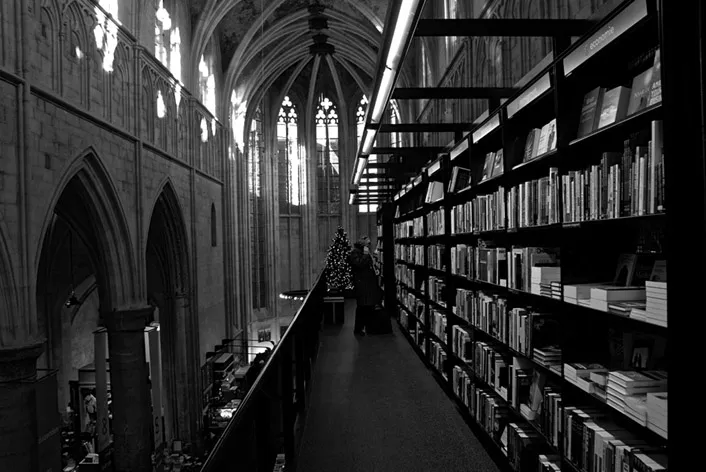

Another much more interesting category of contemporary church use, which will be discussed at much greater length later on in the book, is where the church may or may not have been formally desacralised, but where increasingly its primary purpose is not to act as a place of worship, but as a cultural heritage or tourism destination (Figure 1.2). Perhaps I ought to rephrase that: while the church in these cases remains a pilgrimage destination in an important sense, the pilgrims and that which they come from afar to worship has changed – they no longer come seeking God (or a cure), at least not explicitly, but rather History, Art or Culture. This is a reuse category that most of the great cathedrals of Europe fall into: Notre Dame in Paris, Westminster Abbey in London, St Peter’s in Rome and many more, including, I would argue, Durham Cathedral.

Figure 1.2 Tourists in the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence (photograph © author).

The atheist writer of travel, language and science books Bill Bryson has, famously, declared Durham Cathedral to be the ‘best cathedral on planet Earth’ (Notes from a Small Island). More recently, Durham Cathedral has, in two separate polls, been voted Britain’s best/most-loved building – by BBC Radio 4 listeners in 2001 and among readers of The Guardian in September 2011. Hence the church appears to be commanding the respect and love of people far and wide, including people who don’t subscribe to the Christian faith. This makes it a particularly suitable case study for the examination of what it is in sacred architecture that people continue to respond to in our secular age.

As I’ve intimated, I believe that a heritage cathedral, for example, in a sense constitutes a different – more significant – category of cultural heritage than, say, a heritage castle or manor house. Perhaps there is a form of sanctity that beckons to us through the architecture of these ecclesiastical buildings that we are able to apperceive, and that we in fact continue to yearn for? Perhaps we have emotional, social, æsthetic or spiritual needs that are unmet in our contemporary circumstances and surroundings, that are at least partly being fulfilled in/by a place like Durham Cathedral?

Prior to this, there has not been any research published on Durham Cathedral that focuses on the experience of being in that space, that attempts to interpret this extraordinary example of Norman architecture primarily in terms of its effect. The lack of scholarly attention paid so far to the experience of Durham Cathedral has dictated an approach of combining material on the history and materiality of the cathedral with, on the one hand, material on the hermeneutics and phenomenology of sacred architecture in general; and on the other original first-hand accounts of the place. This primary source material, which forms the empirical core of the work, includes an interview with Canon Rosalind Brown of Durham Cathedral, visitor comments and observations from the Durham Cathedral visitors’ book, and my own observations from a personal visit to the cathedral, written up in the form of an ekphrasis. Nor have there to my knowledge been any scholarly attempts to date to untangle the role sacred architecture, historical or otherwise, may have in alleviating, exposing or challenging the modern condition and secular society.

These are the two manifest gaps in the scholarly literature on historical sacred architecture that I seek to fill. First, the many write-ups of Durham Cathedral shall receive the incremental addition of a phenomenological account of the place. With this stage gained, and in the manner of all deductive efforts, I seek to make a more ambitious contribution, consisting of a pioneering exploration of the psychological and sociological role sacred architecture in general might play in our Western societies today and in the future, as we teeter on the threshold of secularism. I propose to do this by considering the variety of roles Durham Cathedral plays today, both sacred and secular, as a place for worship, a site of cultural heritage and tourism, and as a beloved and much admired piece of architecture.

I do not presume my findings to be conclusory. They do, however, hope...