![]()

1

Pavillon, Cabane, Tabula Rasa: Sources of Modernist Pavilion Typologies

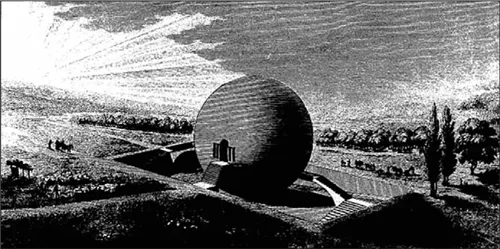

Modern architecture began with a pavilion by Claude-Nicolas Ledoux. So Philip Johnson declared in his 1950 manifesto of formalist modernism, “House at New Canaan, Connecticut” (Illustrations 1.1 and 1.2). Ledoux’s spherical House of the Agricultural Guards for Maupertuis, Figure 7 of Johnson’s notorious picture essay, has the elements that “we”—the modern architects of mid-century, Johnson among them—hold essential: stripped geometric masses, functions each housed in a separate “absolute” shape, mathematical purity of form. These were qualities “dear to the hearts of those intellectual revolutionaries from the Baroque, and we are their descendants.”1 Taking up these forms and spaces, the mid-twentieth-century modernist will succeed Ledoux as a destroyer of old hierarchies.

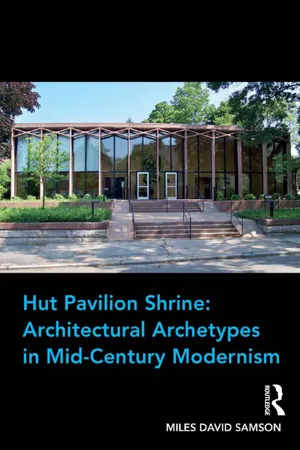

1.1 Glass House, New Canaan, Connecticut. Philip Johnson, 1949. Photograph by Edelteil, Creative Commons.

1.2 Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, “Maison des Gardes Agricoles.” From L’Architecture …, volume II [c. 1804] (Paris, 1847).

All old hierarchies? No: the road to absolute modern form also leads through the approach to the Acropolis, as envisioned by Auguste Choisy in 1899, the essay’s Figure 6. The “revolution” begun by Ledoux also includes an act of recovery.2 There were several such acts in the pedigree of the Glass House, Johnson told his essay’s readers. Mies’s Farnsworth House and Barcelona Pavilion, Le Corbusier’s Ferme Radieuse plan, and Wright’s hillside aerie at Taliesin are not-unexpected points of reference for a modernist design; neither are the abstract art of Doesburg and Malevich. But according to Johnson, Baroque aesthetics, Rococo garden pavilions, casinos by Schinkel, and the English country-house park (and German elaborations of it) are all echoed at New Canaan. Johnson hints to his readers that the naked I-beams of his architecture do not suggest “progress,” but Mannerism’s unbelief in progress. A little scholarly research uncovers how the Glass House, appearing when it did in the Architectural Review, was meant to trigger thoughts about Mannerists and Palladians, landscape follies of the ancien régime, and about “the monumental”—all equally forbidden in modernist practice. Johnson shows the readers of his essay the family tree of un autre modernism, a non-utilitarian one, rescued from mere rationalism and social service.

Johnson’s house and his essay were meant to be provocative, even perverse, as texts on the wellsprings of modernism. Form comes from function, said the main body of modernists, stripping and coarsening Louis Sullivan’s dictum. Form comes from forms recalled from history, said Johnson—some of them revolutionary, but many others not so. Johnson’s were statements of a personal credo but they were not true only of his own work. On the evidence presented in this chapter and the next, formalist mid-century modernism is a recovery of things that architecture culture had tried to do from the fifteenth century onward. Some of them, like Ledoux’s architecture, can be called proto-modernist without too much misrepresentation. Others did not point toward modernism, but were attempts to find essential relations between the human person, the tectonic art, and space as a metaphor for Nature.

Scholars like Vincent Scully and Anthony Vidler have prospected this territory: Vidler building bridges forward from Ledoux and his era toward modernity, and Scully working back from Johnson or Louis Kahn to primal essences. This chapter re-examines the era and the scholarship on it. It asserts that the unraveling of Vitruvian canons and the making of new landscapes of pleasure created a constellation of essentializing architectures. Some of them were important contributions to the understanding of built form, channelings of primal archetypes. Others were “literary” when they were not frankly scenographic. The formalist efforts of the mid-twentieth century depended on both.

Among the typologies accessible to mid-twentieth century architects, the pavilion serves as an especially useful point of inquiry. It took shape in eighteenth-century France and was both explored and typified in the early nineteenth century. Several different types and configurations are part of its legacy to the twentieth century: casino, belvedere, garden loggia, “trianon,” pavillon, maison de plaisance, folie, fabrick or fabrique, Lustschloss. The period between Brunelleschi’s and Alberti’s researches in the fifteenth century and those of Perrault and Fischer von Erlach in the late seventeenth saw the creation, or rediscovery, of most of these prototypes. In the century that followed they were both refined and transgressed. Between Blondel’s presentation of the “character” of the pavilion and Durand’s tables of structures and elements, Laugier and Quatremère theorized the extremes of “natural” and ideal architecture. In Pêre Laugier’s discourses on the essentials of architecture, it is a short step from the pavilions he admired in the gardens of Lunéville, and even from the pavilionated corner blocks and avant-corps of the large urban block, to the single-room cabane that is the first expression and the eternal core of the building art. Quatremère de Quincy schematized and apotheosized the essential cell as architecture’s eternal “type,” never reducible to a checklist of visual cues, yet somehow always displaying Greek form and current French usages. Durand’s system as laid out in his Précis (1802), despite his contempt for Quatremère, turns the latter’s de facto recipes into a very modern text, a checklist of applications for a schematic list of tasks. In French theoretical discourse the forms of the pavilion “family” (so to speak) were thus fitted into systems of signs and forms—taxonomies of types.

The German Romantics attempted to return social and spiritual content to them, from Duke Leopold of Anhalt at Wörlitz to Karl Friedrich Schinkel in Prussia. That Schinkel’s work had in a sense been carried into the modernist ambit by Mies, and was also (less consciously) adumbrated in Wright’s work, made a lifeline back from postwar America to an age of foundational values. The existence of the forms and systems of 1750–1840 gave mid-twentieth-century formalists, or anti-functionalists, an assurance that they were not eclectics or stylistic revivalists. They were, instead, practicing an alternative modern architecture.

In architecture and elsewhere, classification as a way of knowing and of acting upon that knowledge was an agent of disruption as well as order. In the architecture cultures of 1450–1840, the peristyle, the atrium, the tholos, the stoa, the rotunda, the pyramid, and other type-forms were subject to different meanings and different contexts, over and over again, even as the net of Enlightenment categories and uses seemed to tighten around them. The small, self-contained building in a landscape—the pavilion—was the locus of many experiments with them. If pavilions were zones for delimiting and stereotyping architectural forms, they were also occasions for distorting and repurposing them. Transgressive acts of design from the past gave heart to the post-World War II generation, showing that to be a modern was to be a revolutionary as well as a system-builder, even when the architect looked backward for his forms and types. Designs for villas, pavilions, and Utopias in the century before eclecticism took hold were evidence that creative transgression was an available “system.”

This chapter, then, tours the first centuries of “modern” architecture, defining “modern” as Henry-Russell Hitchcock did in his first scholarship—the shift away from the tectonics of the High Gothic to the composition of surfaces of wall.3 Johnson’s ideas of architectural history, like those of his immediate mentor Alfred Barr, were shaped by Hitchcock’s approach. Like Johnson, I am on the alert in the architecture of the pre-revolutionary world for the forms and masses that will mark mid-century formalist modernism. These are the solid, honorific-seeming mass that sometimes manages to be ephemeral on the earth; Doric formality, even dignity; the promise or reality of transparency; and spatial volumes whose shapes suggest the casino’s grand sala or the beat of trabeated rhythm or the universe-echoing dome.

TYPE, MODEL, TRANSGRESSION: RENAISSANCE/BAROQUE/ROCOCO

Quattrocento architecture culture tried to leap from the study of Roman monuments straight to the generation of universal principles. Although Alberti’s De re aedificatoria (c. 1450) exploits archeological knowledge of Roman models, his system does not require or even foreground specific models aside from the general categories of “temple,” town house or villa.4 Alberti’s knowledge of ruined Roman examples and classical theory permitted him to show how all types of building were united by universal rules, and also how every design for a building created a different and unique entity. The study of existing works, however, points toward typological thinking. The architect, Alberti writes, should “inquire whether one and the same kind of design was fit for all sorts of buildings; upon which account we have distinguished the several kinds of buildings … and what sort of beauty was proper to each edifice.” (Prologue).

Alberti’s own typological concerns were somewhat unevenly split between two concerns. One was an attention to types within which the new architecture’s patrons would operate, that is, churches and country villas. The other was the geometrical configurations that embodied universal harmony, embodied in different types and not determined in a narrow sense by those types’ usages. In the end, the practical requirement of a roof over walls and the idealizing concept of the building as a “body” were the only archetypal elements De re aedificatoria declares to be essential.5 To have a mental catalogue of good examples of buildings, or to judge the effectiveness of a form in a given usage of building—both recommended by Alberti—does not mean that architecture is a matter of the eternal replication of any archetypal form. In the end, the architect’s loftiest goal should be to create a design for which no precedent exists. (IX, 10) This is completely compatible for Alberti with his own highest category of design, the making of a city of buildings obeying universal laws, shaping a harmonious society.

The ambiguities of both Brunelleschi’s and Alberti’s practices in their use of Roman sources in “lawful” ways are seen particularly clearly in their relationships with a specific Roman building. This was a pavilion: the domed, polygonal fourth-century kiosk in the Licinian Gardens, open to the air, which for centuries went unidentified but in the sixteenth century came to be called the “Temple of Minerva Medica.” Until fairly recent times its dome remained intact, making it the largest surviving rotunda structure in the city after the Pantheon. Its free-standing isolation on desolate grounds also made it especially striking. Its scheme of a full-height chamber ringed with deep niches can be seen in a late, unfinished work by Brunelleschi, the oratory of the Florence monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli (1434–37), and one of Alberti’s last projects in Florence, the redesign of Michelozzo’s tribune of the Santissima Annunziata (after 1450-before 1470).6 The evidence for the Florentines’ use of the “Minerva Medica” as model or prototype remains ambiguous. While scholars from Heydenreich to Peter Murray have called it an intentional replication, more recent historians are reluctant to point to any one edifice, Roman or medieval, as the prototype. Where one might expect Alberti to give testimony about the Licinian kiosk, which he seems to have believed was a temple, he listed “the Baths and the Pantheon” as his inspirations for the Santissima Annunziata. Other models—actual and metaphorical—were just as close at hand. Tavernor cites the Tomb of Theodoric in Ravenna and even the martyrium of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher as models for Alberti’s round or centralized “temples.” Medieval round types, like the Italian free-standing baptistery, offered far more practical models for centralized designs than any antique structure.7 But if Alberti did not literally take the Licinian kiosk as a model, he did use a Classical type as a basis for a contemporary design, exploiting both antique description and physical remains. The Etruscan temple, as visualized both from Vitruvius’s description and from a mistaken interpretation of the Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine, is not only advanced as a possible model for architects’ use, but was used by him in designing San Andrea in Mantua. Even here, creative misunderstanding of Roman evidence resulted in a building that replicates no existing model.8

Francesco di Giorgio’s manuscripts and drawings offer typologies of the new architecture, and illustrates several different possible versions of two of them. One is the rotunda; Francesco offers several of them as reconstructions of antique examples but they are probably original designs. The other is the house, which is presented in several different types depending on social rank and fashion. The Roman atrium features in these house types, in a variety of shapes, reflecting Francesco’s continuing efforts to understand the spatial type as Vitruvius had described it. By this point, Roman precedent, and Romans’ efforts to describe and categorize forms and spaces, was becoming as necessary to architecture’s rebirth as the order and measure which Classical form seemed to have.9

Sebastiano Serlio, in the books of his “treatise” (1537–75), concerns ...