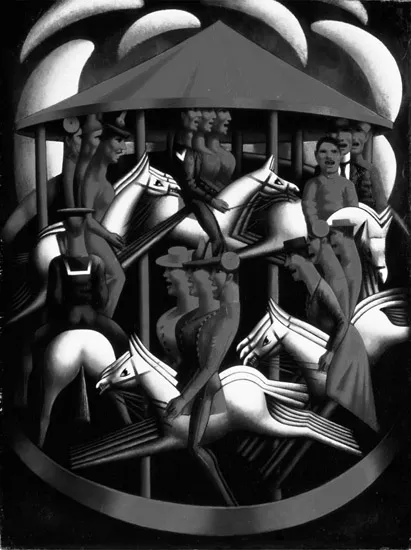

The Merry-Go-Round

The work of Lawrence and Mansfield emerges from the context of the Great War and indicates modernist preoccupations with social dance. In that emergence, their work relies on portrayals of social gatherings as at once stultifying and destructive, but also ripe with potential.1 In Lawrence’s hands, the dance underscores the endurance and unassailable centrality of the heterosexual couple in the renewal of society; in Mansfield’s, it offers a peculiar blend of collective pleasure and a stage for flirtation which empowers women to reject the couple (indeed, marriage and domesticity). Lawrence rejects the social gathering of dancers in combinations much larger than two; Mansfield is more sympathetic to such gatherings as the context for a newly empowered postwar femininity. This chapter will compare and contrast Lawrence’s and Mansfield’s representations of social dancing in the context of the Great War’s shaping of intellectual and artistic visions.

To grasp the meaning of social dancing and its connotations of mechanized leisure in that context, there may be no better illustration than the 1916 Merry-Go-Round by Mark Gertler, the Jewish painter intimately acquainted with both Lawrence and Mansfield (Fig. 1.1). Now hanging in the Tate Museum, over the course of the twentieth century this monumental, towering painting (6 × 4 feet/1.83 × 1.22 meters) has become “an iconic image of the First World War, easily recognizable as an image of cultural discontent.”2 Grace Brockington, in her discussion of modernist art and pacifism, has underscored its eloquent expression of dismay at the war shared by many of the London artists and intellectuals of the time.3 Because of his Austrian parentage, Gertler did not fight in the war, observing it, aghast, like Mansfield, Lawrence, and others, from a distanced perspective. According to Gertler’s biographer, the idea for the painting originated in a bank holiday fair on Hampstead Heath, but “by 1916, with the general atmosphere permeated by ‘war fear,’ the fair had become a symbol for something far more sinister,”4 and friends who saw the painting in his studio recognized it as pointedly anti-militaristic. Cautious about the controversy it might arouse, Gertler did not exhibit it immediately; when it was exhibited in 1917, the Evening News called it “a shriek, a groan, a hoot, a blare, a tempest of wild rending;” the Pall Mall Gazette described it as “horribly out of tune,” “a piercing and offensive noise.” The Sunday Times, however, hailed Gertler “at his brazen best” and the painting as “a riot we almost hear as we enter the gallery … the apotheosis of the steam-organ in paint.”5 Despite the fears of Gertler and his friends the press did not accuse the painter of anti-militarism. However, one viewer—D.H. Lawrence—thought the painting was a masterpiece precisely because of its ability to distill and consolidate the problem of the war. Having received a photograph of the painting when he was living in Cornwall in 1916, Lawrence wrote a passionate letter enthusing about it to Gertler:

Your terrible and dreadful picture has just come. This is the first picture you have ever painted: it is the best modern picture I have seen: I think it is great, and true. But it is horrible and terrifying. I’m not sure I wouldn’t be too frightened to come and look at the original.

If they tell you it is obscene, they will say truly. I believe there was something in Pompeian art, of this terrible and soul-tearing obscenity. But then, since obscenity is the truth of our passion today, it is the only stuff of art—or almost the only stuff. I won’t say what I, as a man of words and ideas, read in the picture. But I do think that in this combination of blaze, and violent mechanized rotation and complete involution, and ghastly, utterly mindless human intensity of sensational extremity, you have made a real and ultimate revelation.6

Figure 1.1 Mark Gertler, The Merry-Go-Round, 1916. Tate Museum. Tate Images

As we shall see, while in Cornwall Lawrence was developing his apocalyptic vision of the war as symptomatic of cultural self-destruction, and his language here of “violent mechanized rotation and complete involution” echoes so many of the laments that emanated from Lawrence’s Cornish exile. Obviously, the painting struck a deep chord in Lawrence, especially in its ability to make a common symbol of play and entertainment into an image of mechanized, mass death.7 And what better expression of Lawrence’s hatred of “merging”?8 Lawrence’s dismay at war resonates with his dismay at social gatherings such as bank holiday fairs or large parties. Significantly, the carousel is a metaphor both for the war machine and for a paralyzing routine of leisure.9 Gertler’s painting also conjures the material conditions of British fairgrounds of the turn of the century such as those of Nottingham’s Goose Fair, where multiple carousels offered cheap entertainment and spectacles of massed humanity.10

I take The Merry-Go-Round to provide an image of what social dance and mechanized leisure looked like when they were most loathed. The carousel literalized, in the form of an actual machine carrying human bodies, what social dance figured to critics of modernity: a passive capitulation to mechanical forms of social life, frozen smiles glued to rigid faces, grimaces of “delight” at being whirled about, bodies rendered indistinguishable from each other in rigid repetition. The painting represents an “oppressive cycle, seeming to obliterate freedom of action.”11 We have seen that Lawrence responded to the painting immediately; later, I will show how he re-articulated his response by portraying Gertler as the artist Loerke in Women in Love and by rendering The Merry-Go-Round as Loerke’s frieze of frenzied dancers.12

Gertler also influenced Mansfield; like Lawrence, she portrayed him in her fiction.13 There is no obvious rendition of the painting in Mansfield’s work such as Loerke’s frieze in Women in Love. Yet, while there is no direct evidence of it, it is tantalizing, given the title of Mansfield’s story “Bank Holiday,” to imagine a connection to Gertler’s work, originally inspired by a bank holiday. At the very least, the bank holiday inspired both Gertler and Mansfield to create works of art about festive crowds. At the end of this chapter, I shall return to “Bank Holiday” to understand it as a less threatening version of leisure than Lawrence’s. Mansfield’s own exploration of social dancing as a potentially dangerous conformity contains within it the opportunity for authentic pleasure and release.

First, though: Lawrence and his fear of dancing, groups, and war.

Lawrence’s Social Vision in Cornwall and Women in Love

Dance figures in other novels by Lawrence, especially in Sons and Lovers, The Rainbow, The Lost Girl, and Lady Chatterley’s Lover, but I focus on the dances of Women in Love (1920) because in that novel we can best see Lawrence becoming the apocalyptic, anti-war, exilic modernist struggling to reconceptualize subjectivity and society, and insistently, even obsessively, using dance to do so.14 Women in Love originates modernist engagement with social dancing in its response to war, expressing a crucial sensibility that encounters dance not as a form of freedom, but as a threatening group formation. While the modernist sensibility longs for wholeness and integration, it recognizes this longing as potentially seductive, indeed dangerous, and social dancing comes to represent both the allure and the danger of such social coherence.15

Within months of outbreak of the Great War, Lawrence and his wife, Frieda, found themselves living intimately with other couples, first in Buckinghamshire, with Gilbert and Mary Cannan and John Middleton Murry and Katherine Mansfield. The meaning of this intimacy is distilled in Catherine Carswell’s early account of Lawrence’s life: “The events of 1914–1919 all went to strengthen his strong and simple belief that the only thing to be done was for a few people to go together to some distant refuge and breeding place of newness.”16 The “breeding place” shifted from Buckinghamshire to Cornwall, the company diminished, but the idea remained the same: Lawrence was committed to the few vs. the many. The utopian few he imagined was sometimes named “Rananim”; Carswell explains the origins of this name: “Ranani zadikim b’Adonoi. [S.S.] Koteliansky [the Jewish, Ukrainian immigrant translator] had sung the Hebrew chant to them in Bucks as the war horror arose and increased, and it intensified the longing Lawrence had always felt to live remotely with a group of kindred spirits” (22). The phrase, the first line of Psalm 33, means “Rejoice in the Lord O ye Righteous”; Lawrence’s biographer Mark Kinkead-Weekes glosses “Ra’annanin” as “green, fresh, or flourishing,” underscoring the connotations of regeneration in Lawrence’s “Raninim.”17 John Worthen usefully describes Rananim as “consoling” and as a “liberating communal fiction.”18 Lawrence longed for the gathering of an intimate few in rejection not only of the many being drawn into war, but of the centripetal force of social gatherings he found overwhelming and unable to provide him with domestic stability: those of the intellectual and artistic coteries of Bloomsbury, Cambridge, and Garsington Manor, which Lawrence visited in 1915. Garsington’s house parties epitomize the kind of social gathering to which Lawrence’s wartime refuge stands in starkest contrast. Importing London society to the country for occasionally frenzied dance parties provided a model against which Lawrence pushed when he imagined a more authentic, intimate, and regenerative existence: an alternative to Morrell’s salon sociability.19

Lawrence, a writer infamous for pushing boundaries of propriety and convention, was keenly interested in finding ways to describe psychological and physical conditions in which individuals could do very little pushing at all: states of surrender. To discern the theory of character in Lawrence’s fiction, critics have frequently turned to the letter he wrote to Edward Garnett from Italy in June 1914.20 There, Lawrence compared the new conception of character in his novel in progress to allotropy, “the variation of physical properties without change of substance” (OED).

You mustn’t look in my novel for the old stable ego—of the character. There is another ego, according to whose action the individual is unrecognisable, and passes through, as it were, allotropic states which it needs a deeper sense than any we’ve been used to exercise, to discover are states of the same single radically unchanged element.21

Lawrence is arguing with Garnett about the status of characters, psychology, and the “non-human” element in the draft of Women in Love, then titled The Wedding Ring. Lawrence rejects the “dull, old, dead” moral scheme of the Russian novelists (Turgenev, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky) and embraces the Italian Futurist F.T. Marinetti, whose writing about “the inhuman will, or … physiology of matter” fascinates him. At the end of his reflection on character, physiology, and allotropic states, Lawrence states: “Don’t look for the development of the novel to follow the lines of certain characters: the characters fall into the form of some other rhythmic form, as when one draws a fiddle-bow across a fine tray delicately sanded, the sand takes lines unknown.”22 Lawrence sees his novel in process as “a bit futuristic.”23 It rejects the “old-fashioned human element” for a new conception of characters based not on individual will or agency, nor on the stability of the ego, but on a kind of passivity, a succumbing to essential, unchanged substance, and, thus, the surrender of the “stable” ego to a state of relative fluidity, or allotropy’s “variation” of physical properties. That combination of passivity and fluidity is imagined by Lawrence in the image of characters “falling” into “some other rhythmic form.” His theory of character relies implicitly on music and dance to figure the passivity and fluidity he regards as necessary to conceiving a new, more truthful account of human existence. “When one draws a fiddle-bow across a fine tray delicately sanded, the sand takes lines unknown.” The rhythm is now the fiddle-bow, the characters, the sand. When the characters fall into a rhythmic form, they take “lines unknown.” Lawrence grasps for a way to say that his characters are not in control, that they are subject to physiological and environmental determinations with unpredictable results. In order to convey the idea that personhood involves a combination of unchanged essence and physical variation, he relies on the metaphor of a fiddle-bow acting on grains of sand: a person is an assembly of grains, the grains do not change, but their arrangement takes different shapes. “Rhythmic form” and “fiddle-bow” are as crucial to this letter’s vocabulary as the more well-known “allotropy,” and they even point towards the insistent use of scenes of social dance to describe the physiological and environmental determinations of group formations.

The interest in group arrangements that would find its most developed expression in Women in Love is illuminated by the letters Lawrence wrote in 1916 and 1917 from Cornwall, where he and Frieda rented a cottage, and he imagined reinventing the world in the midst of war. These letters evince Lawrence’s urg...