![]()

Chapter 1

Jurisdiction, Hierarchy and Actors

Introduction

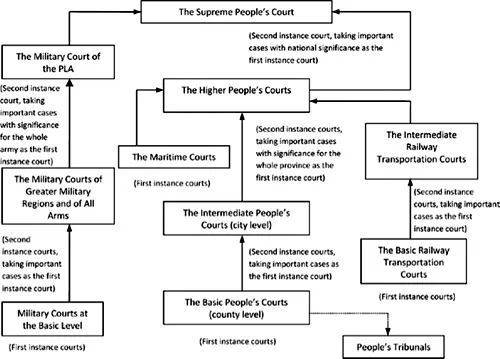

Courts in China consist of the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) at the central level, local people’s courts at three levels, and special people’s courts. Local courts are established on the basis of administrative divisions; they include 32 higher people’s courts (HPCs) which can be found in the capitals of provinces and autonomous regions, and four municipalities directly under the central government (Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin and Chongqing); 409 intermediate people’s courts (IPCs) in prefectures and cities; and 3,117 basic people’s courts (BPCs) at the county level, including districts within cities.1 Special courts include maritime, railway transportation and military courts. Maritime courts adjudicate all forms of maritime cases. They are established at the intermediate level and handle only cases of first instance; appeal cases are handled by the higher people’s courts. Rail transportation courts are erected along the main railway lines and function at both the basic and intermediate levels. Military courts comprise three levels and handle both criminal and civil matters concerning military personnel.2 The SPC serves as the highest instance court for military cases. The structure of the court system is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Conventionally, Chinese courts operate a two-tier appellate system. A party may appeal a judgment or the decision of a local court to the corresponding court at the next level; judgments or decisions given at this elevated level are final. However, special trial supervision procedures are in place which have the potential to re-try a case, despite an effective judgment having been given. In addition, for cases involving the death penalty, upon the judgment of a second instance court, a subsequent procedure of review by the SPC exists.

Figure 1.1 Structure of the Chinese courts

Each court has several trial chambers and administrative divisions. Trial chambers are divided into criminal, civil and administrative chambers;3 other substantive divisions cover case filing,4 enforcement of judgments, trial supervision and research. The administrative division includes a general administrative affairs office, a personnel office and a judicial administrative apparatus office (sifa xingzheng zhuangbeichu), which presides over the management of permanent assets, vehicles, police facilities of the courts and so on. A distinctive feature of the organisational aspect of the Chinese courts is the presence at each court of a Communist Party organ to ensure that the Party’s policies are followed by both the courts and the judges.

In administering justice, Chinese courts apply the collegiate panel system. All first instance cases are brought before a collegiate panel of judges or a combination of judges and people’s assessors. However, with simple civil cases, minor criminal cases and cases otherwise provided for by the law, these may be tried by a single judge. In practice, at BPCs any minor criminal or simple civil case will be handled by a single judge, whereas courts at the intermediate level and courts at a higher tier will use the collegiate panel system.

This chapter examines some of the basic features of the court system in China. It begins with a description of the jurisdiction of courts at the various levels and locations, as well as the special jurisdiction afforded to the handling of cases with foreign elements. It then explores the vertical relationship between the higher and lower-level courts, and the varying supervisory role that exists between them. Such supervision tends to be seen in the systems of remand for re-trial (fahui chongshen), the re-opening of a trial (zaishen) and requests for instruction by a lower-level court to a higher-level court (qingshi baogao zhidu). With regard to the trial system as a whole, the functions of people’s assessors and the adjudication committee in the trial process reflect particular Chinese characteristics, and thus are also examined in this chapter. Though the people’s assessors system was largely overlooked during the course of the 1990s, its resurgence in the 2000s and its promotion by the SPC as part of the judicial democratisation movement continues to generate much debate in present-day China. The adjudication committee system reflects the collective leadership within a court on adjudicating cases; its functions, procedure of working, and its positive and negative effects in realising a fair trial and judicial independence are discussed.

Jurisdiction of the Courts

The jurisdictions of the various courts are set out in the Organic Law of People’s Courts (OLPC),5 the Criminal Procedure Law (CrPL), the Civil Procedure Law (CiPL), the Administrative Litigation Law (ALL) and a number of the SPC’s judicial interpretations.6 They can be classified into jurisdiction by levels (jibie guanxia), territorial jurisdiction (diyu guanxia), transferred and designated jurisdiction (yisong and zhiding guanxia), and jurisdiction over foreign-related cases.

Jurisdiction According to Level

This is also commonly referred to as tier jurisdiction or hierarchical jurisdiction, which alludes to the division of the work-load and authority between the four levels of the courts.7 The basic principle of jurisdiction in this regard is that most cases are handled by the BPCs; yet, cases concerning large amounts of money, with a more profound societal impact, or concerning special subjects such as foreign citizens or legal persons, large state-owned enterprises or higher-level governmental organs and officials, are dealt with by either IPCs or HPCs. In principle, the SPC does not handle cases of the first instance.

The BPCs are the lowest-level courts. They may establish people’s tribunals according to the conditions of the locality, population and cases. A people’s tribunal handles ordinary civil cases, directs the work of people’s mediation committees, organises legal propaganda and receives people’s letters and visits. Such a tribunal is a part of the basic people’s court structure and any judgments or orders given have the same legal effect as those made by a BPC.8 The overwhelming majority of lawsuits begin and end in BPCs. Generally speaking, the judges at BPCs are the most experienced adjudicators. However, many judges at this level do not retain the expected standard of university education in the legal field, which in turn affects the quality of justice attained.9 A commonly cited depiction of BPCs centres on the notion of ‘three 80 per cent’ statistics: they handle approximately 80 per cent of first instance cases; approximately 80 per cent of the judicial personnel across the whole country work at this level; and roughly 80 per cent of judicial corruption cases occur at the BPC level.10

IPCs, as the second-lowest people’s courts, are established in prefectures of a province or autonomous region, in municipalities directly under the central government, in municipalities directly under the jurisdiction of a province or autonomous region and in autonomous prefectures. They handle cases of first instance assigned by law; cases of first instance transferred from the basic people’s courts; cases of appeal and of protests lodged against judgments of the basic people’s courts by the people’s procuratorates; and cases of protest raised by the people’s procuratorates in accordance with the trial supervision procedure.11

The criminal, civil and administrative procedural laws all contain certain provisions which categorise the cases to be specifically handled by the IPCs as the first instance court.12 According to the Criminal Procedure Law, these cases include those involving threatening national security or terrorist activities and criminal cases which may involve life imprisonment or the death penalty. Under the Administrative Litigation Law, IPCs are authorised to hear cases concerning the verification of patent rights; customs-handling; suits against administrative actions taken by State Council departments or governments at the provincial level; and other significant and complex cases. According to the Civil Procedure Law, IPCs have the authority to preside over cases involving foreign elements; cases which have major ramifications; any disputes regarding their jurisdiction; and cases brought by order of the SPC.

HPCs handle cases of first instance which have been assigned by the law; cases of first instance which have been transferred from the people’s courts at lower levels; cases of appeal and of protest lodged against judgments of lower people’s courts; and cases of protest lodged by people’s procuratorates in accordance with the trial supervision procedure.13 HPCs review cases of first instance in which the death penalty is imposed by an IPC and the accused renounces the right to appeal. If a HPC raises no objection to the death penalty sentence, it then submits the case to the SPC for their final approval; if the latter disagrees with the death penalty sentence, it can either re-examine the case or remand the case back to the original IPC for re-trial.14 Regarding civil cases, HPCs are courts of first instance for cases that are deemed to have a potentially significant impact at the provincial level. Typically, the amount of money under dispute in a case determines which tier of the court structure will have jurisdiction to adjudicate.

The SPC is the highest judicial organ of the state. It has jurisdiction as the court of first instance over cases which are likely to have a major bearing on the country as a whole. Cases which the SPC has jurisdiction over, as the court of final instance, include cases of appeal, cases of protests lodged against judgments of HPCs and special people’s courts, and cases of protest lodged by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate in accordance with the trial supervision procedure.15 However, in practice, the SPC has rarely handled any cases of first instance; the exception being the 1978 trial of the ‘Gang of Four’.16

While the jurisdiction of the various courts, according to a tier structure, is generally provided for in the three aforementioned procedural laws, the SPC has issued a number of judicial opinions to clarify and reset a number of rules on court jurisdiction at the different levels. This is typically reflected in the handling of three types of civil and commercial cases: cases involving large sums of money, intellectual property cases, and cases with foreign elements.

As cases involving large sums of money have increased, the caseload of the HPCs has also multiplied. If an HPC acts as the first instance court, parties appeal to the SPC, and this consequently increases the SPC caseload. To tackle this problem, in 2008 the SPC issued the Notice on the Adjustments of Jurisdiction Standards of Higher People’s Courts and Intermediate People’s Courts over Civil and Commercial Cases of First Instance,17 to raise the threshold criteria for determining when a case is to be handled by IPCs and HPCs. For instance, for a case to be accepted by a HPC in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong, Jiangsu or Zhejiang provinces, the disputed amount cannot be less than RMB 200 million; for a case to be accepted by a HPC in Tianjin, Chongqing, Shandong, Fujian, Hubei and others, the disputed amount cannot be less than RMB 100 million; for a case to be accepted by a HPC in Gansu, Guizhou, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia and Yunnan, the disputed amount cannot be less than RMB 50 million. In order for a case to be accepted by an IPC in Beijing, Shanghai, the capital cities of Guangdong, Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces, and other economically-developed cities, the disputed amount has to be above RMB 50 million.

With regard to intellectual property cases, the Opinions on Several Issues concerning the Implementation of the Civil Procedure Law issued by the SPC in 199218 provides that patent disputes are to be heard by those IPCs to be decided by the SPC. In January 2010, the SPC issued the Notice on Adjusting the Standard for Jurisdiction of Local People’s Courts at All Levels over First Instance Civil Cases Involving Intellectual Property Rights19 which stated: (1) for cases with disputed amounts over RMB 200 million, or over RMB 100 million where one party concerned is not domiciled within the area of jurisdiction or where the case involves foreign characteristics or matters relating to Hong Kong, Macao or Taiwan, the first instance jurisdiction will be conferred upon the HPCs; (2) for cases below the aforesaid amount, except for especially-designated local people’s courts, the first instance jurisdiction will be conferred upon the IPCs; (3) some BPCs designated by the SPC are capable of trying cases involving intellectual property rights at the first instance where the disputed amount is less than RMB 5 million, or between RMB 5 million and RMB 10 million where the domiciles of both parties are within the area of jurisdiction of the HPC or IPC to which the basic court belongs.

In January 2010, the SPC also issued the Notice on the Standards for Some Basic People’s Courts’ Jurisdiction over Civil Cases of First Instance Involving Disputes over Intellectual Property Rights.20 These two Notices comprehensively adjusted and unified the standard for the jurisdiction of courts at all levels over civil cases involving intellectual property rights. In general, the scope of jurisdiction of basic courts over general civil cases involving intellectual property rights has been ...