![]()

Part I

Introduction

In the early 1990s, when I was a practising architect in India with a master’s from the United States and a mother of two girls, I had a personal crisis. I suddenly realized that my career had reached nowhere close to what I had imagined it to be in the heady days of being at the top of my class in high school. This dilemma sent me on a search that has taken more than 25 years. During this period, as the cliché goes, the personal became political for me. It has been at times a lonely walk, at other times very enriching and fulfilling, with the collective experience touching other women. This book is a culmination of that long journey that began when my feminist consciousness grew, eventually bringing gender and architecture together in my life. The entire experience has, however, given me tremendous positive energy as my network of women in architecture grew and some of them became close friends for life.

It all began when I presented a paper at an Indian Institute of Architects’ seminar in Ahmedabad in 1991 on being a woman in architecture in India. This led to an informal meeting of about 50 women in Ahmedabad forming a loose-affinity organization called Women Architects Forum (WAF). In 1992, WAF had a much larger and more formal gathering at the Kalina Campus of Mumbai University, followed by one major and a few minor events, including my editing the newsletter of WAF from 1993 to 2001 for private circulation.1 However, WAF never grew as a movement, but everyone involved in it took something back from it, directly or indirectly. My interest in women as creators of the built environment was followed by my inquiry into women as consumers of space. Therefore, along with Ismet Khambatta, I organized the first national conference in India on gender and space in Ahmedabad in 2002 called Gender and the Built Environment, which also resulted in my editing a book of the same title. The seeds of this book were, perhaps, planted then.

Women and architecture in India

‘Although women were the original builders … in society, they have historically been on the fringe of the architectural profession throughout the world. In fact women have been assigned passive and marginal roles in the intellectual process that differentiated “building” from “architecture”.’2 In India also, from ancient times, the knowledge and the science of town planning and architecture, vastu vidya, was handed down from the sthapati (architect) to the apprentice. Oral traditions got translated into canonical texts and were later interpreted as regional guidebooks.

In India, women architects are not part of the Indian tradition. The Vastu Shashtras allowed only men to be architects. However, the indigenous traditions have always had women builders participating in the actual creation and production of architectural images through the use of their skills in construction, preparation of materials, rendering and decoration.3

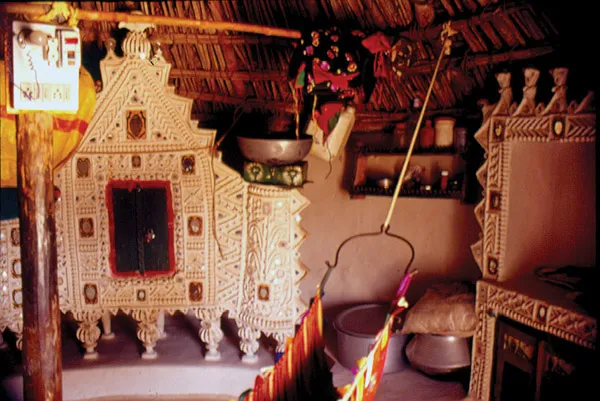

For example, in the Bunni area of Kutch in Gujarat, there is a traditional gender division found in the making of a house (called Bhunga). Men of the family dig the foundations, make mud bricks and do other major building constructions like walls and roofs. Women, on the other hand, are involved in the finishing activities which are artistic in nature and add a sense of aesthetics to the house. They do cow dung plastering of floor and walls as well as mud relief and mirror work on the walls that add a wonderful ambience to the house.

Women also white wash the inside of the home and use coloured mud to paint the outside.4 In other traditional building-related and product-making activities, women also play a significant role. For example, all over the subcontinent, women prepare the clay in a potter’s community and also assist the men in the building as well as breaking of the kiln. They colour and pebble glaze the objects produced though the men are in charge at the wheel and the final products are associated with them.5 Women have been part of cultural production for ages. They habitually create household art such as patch work, painting and weaving in their everyday lives. Unfortunately, no one has so far delved into or documented the contribution of women (in visualization and design) in traditional building crafts or building processes. Therefore, in the perception of the society, only men have been strongly associated with the creation of the built environment. In the medieval time, the act of building remained in the hands of various craftsmen guilds until the colonial intervention when modern institutions and disciplines replaced the traditional systems and the professional education of women gradually increased.

Plate I.1 The interior of a Bhunga in Kutch

The discipline of architecture developed a separate identity apart from engineering in India through the 20th century. In the first half of the 19th century, architectural design was largely in the hands of military and other engineers during the colonial rule. In the second half, however, British and other European architects began to execute specific commissions or to set up their own practices. Many Indian architects, educated in India or abroad, joined British firms over the years. As the century progressed, Indian-headed firms challenged the Anglo-Indian offices for professional hegemony.6 Thus, although design is an ancient art in South Asia, the profession of architecture is relatively young. Since architectural production is closely linked to the socio-cultural context, the profession has mostly remained the prerogative of men throughout this period, creating a dominant masculine culture as in the other parts of the world. The contribution of women has remained rather vague and marginal even though there is much to celebrate in terms of the achievements of women in architecture in the past few decades. This book attempts to fill this lacuna in the professional landscape.

The need for this book

An examination of Indian architectural discourses in history and theory reveals that, for the most part, issues of race, gender or class do not figure in scholarship. However, in a number of disciplines parallel to architecture, scholars have challenged perceived notions of power, form and identity. In philosophy, health, sociology, history and media, feminist thinking has affected the production of knowledge and the modes of representation. In literature as well as cultural, postcolonial and gender studies, to name but a few, the question of ‘difference’ has been explored in new and innovative ways and attempts have been made at reconstructing history from the gender angle. But within the discipline of architecture, its marginalization in oral or written mainstream discussions has affected both theory and practice. This exclusion has also submerged the role of feminist knowledge in the narrative. ‘A systematic consideration of gender is a fundamental condition of any adequate analysis or knowledge of contemporary society.’7 Thus, it is central to architectural thinking to understand the complex involvement of women in architectural production, representation and space utilization.8 This book delves into this contested territory and attempts to bring together the roles of feminism and modernity to the making of architecture.

In the past two decades, there has been a sharp increase in the number of women joining architectural degree courses in India. Yet there has certainly been a lack of female presence in the profession. A few successful women architects are taken as evidence that there are no barriers to women’s total acceptance. The gap between politically assumed/constitutionally guaranteed gender equality and the ground reality, though decreasing day by day, is still vast and needs to be recognized.

The success stories of women architects are yet to be acknowledged as part of history, theory or the contemporary scene. These are viewed as exceptions. There is a definite absence of role models and mentoring of younger girls by women with achievements.9

A large number of institutions teach architecture in the country at present, where 40% to 60% of the student body admitted each year are women, but only about 15% to 20% are eventually active in the field.10 Though a high number of young women join architectural offices as fresh graduates, they find it hard to keep going due to several reasons discussed later. In the collective consciousness of the society and the profession, the educational environment is gender neutral although women have minimal visibility in the public domain, marginal leadership positions and a non-iconic presence. Belonging to the post-feminist generation, the young female students generally believe that equality has been achieved in their world. They are blissfully unaware of any of these issues; the majority are in complete denial and react with resistance and scepticism to them.

Plate I.2 Architectural students in a class at CEPT University, Ahmedabad.

There are a very limited number of single woman-headed large practices in India even today in the 21st century. Women’s practice was almost exclusively associated earlier with domestic architecture and/or interior ‘decoration’. Though the perception of the society is beginning to change, this stereotype dominates in contemporary times. Architecture is a difficult profession as recognized the world over. Setting up one’s own practice is a challenge for all architects. But women face an extra set of battles that raise their dropout rate in the profession.

To a certain extent, all architects struggle to survive and excel in a profession where the educational preparation is long … the hours are gruelling and the pay is incredibly low. Yet many unrepresented architects [women] face additional hardships, such as isolation, marginalization, stereotyping and discrimination.11

It is difficult for women to realize that they require not only a full-time commitment to their careers but also sophisticated business and management skills in organizing the home as well as office. Shimul Javeri Kadri, featured in this book, feels that young women are left behind in the profession when they have to juggle family and work without adequate support. In other creative professions like media or graphic design, they have a lot more opportunities to lead and have an independent practice. It is primarily because it takes a long time to be recognized in this profession. The period of investing in a woman’s career generally overlaps with having a family and raising children among other things. The long hours and relatively low pay scales are further deterrents. If a break is taken to raise a family, then it is difficult for her to catch up as the situation changes in a few years, in terms of professional set-ups, building technology, materials and even software.12

So what happens to the hundreds of women who graduate every year? Because of architecture’s association with the arts, it falls in the category of design professions, in spite of its close connection with science, engineering and technology. Today, there are only about 30 recognized institutions that teach design (textiles and fashion, graphics, furniture, product, animation, film, etc.).13 In the 1960s and 1970s, there were only a handful. However, these two related disciplines are interlinked, with the field of design having undergone feminization in the second half of the 20th century. Due to the versatile and all-encompassing nature of architectural education, most graduates believe (rightly or wrongly) that they have the ability to shift between them, especially in an age when the clarity between the two is rather ambiguous. Therefore, many graduates of architecture are found to be successful in a variety of design fields. A majority of them typically veer off especially towards interior design. Some architects eventually shift towards graphics, textiles, fashion, photography/film or furniture design when their careers fail to make su...