![]()

Chapter 1

Performing Women in English Books of Ayres

Scott A. Trudell

Like other composers of the 29 “books of ayres,” or songbooks for lute and voice printed in London between 1597 and 1622, Thomas Campion frequently seeks to represent and ventriloquize the female voice.1 The following lyric, from Campion’s 1617 Third Booke of Ayres, idealizes female eloquence with an accompanying sense of nostalgia and loss:

Awake, thou spring of speaking grace, mute rest becomes not thee;

The fayrest women, while they sleepe, and Pictures equall bee.

O come and dwell in loves discourses,

Old renuing, new creating.

The words which thy rich tongue discourses

Are not of the common rating.

Accruing a moving force without breaching the boundaries of decorum, the female subject’s vocal power is specifically derived from music and performance:

Thy voice is as an Eccho cleare which Musicke doth beget,

Thy speech is as an Oracle which none can counterfeit:

For thou alone, without offending,

Hast obtain’d power of enchanting.2

When it awakens in or from a gendered domestic space, this female voice promises to be a singular phenomenon, “alone” able to transcend a static “Picture” and deeply move her auditors.

Well known for his dual talents as a poet and a composer, Campion might be said to exert a unique amount of influence over the production of his ayres, down to the tones and rhythms with which they are performed. Yet even he has a notable lack of control over the performance environment of songs, including this one, which were collectively distributed among poet and composer, musician or group of musicians, and vocalist or vocalists, who could have been either male or female. The singer’s portrayal of gender is guided, of course, by Campion’s words and the literary tradition that informs them. Everything from the singer’s pitch to his or her masculine- or feminine-coded gestures would also shape the song’s presentation of gender, as would word-painting on the part of the composer and expressive ornamentation on the part of the vocalist or lutenist. What is perhaps less obvious is how gender norms in Campion’s lyrics are themselves influenced by performance conditions. Aware that his ayres were being marketed to and performed by women, and sensitive about his position as a composer of volumes associated with a domestic, amateur milieu, Campion is to some extent answerable to female consumers and performers. Purchasing books of ayres in the print marketplace, gathering around these folio editions in order to perform them in domestic settings that include women, practicing ayres in private so as to teach oneself lute, viol, or voice—all of these activities are part of a broader continuum of musical and poetic production that even the versatile Campion cannot monopolize.

With this in mind, it becomes less surprising that “Awake, thou spring of speaking grace” figures the female voice as an “Eccho,” since, as Gina Bloom and others have shown, the division between voice and body in the Echo myth was often associated with a paradoxical female agency during the period.3 Even as the Echo comparison suggests that the speaker merely imitates the harmony of composed music, the sense that sound is unmoored from subjectivity raises the possibility that her voice is independent and powerful in its own right. Campion’s lyric wants to have it both ways: the female voice is, on the one hand, “as an Oracle which none can counterfeit,” a faithful representation of its vatic source, and, on the other hand, an expressive phenomenon that is threateningly inimitable. Campion summons up a disembodied type of female eloquence that is sleeping or resting vaguely in the past, not least because an Echoic voice promises to be an obedient instrument for a male poet and composer. Yet it is precisely the awakened, embodied, performative qualities of this voice that are described as moving and enchanting. Campion is grappling with a moment of cultural contradiction surrounding gender and song—a sense that women are asserting a new kind of influence over books of ayres even as the female gender continues to be treated as a mouthpiece for male preoccupations and ideas.4

Composers of books of ayres—all of whom were male—consistently chose to set poems in which the female voice figures prominently, including over 30 “female persona” ayres and more than a dozen dialogue ayres that include female parts. As we shall see, many early modern women were accomplished vocalists and instrumentalists, and composers’ prefatory materials note the influence of female patrons and allude to female musicianship. In turn, countertenor (upper-range) male vocalists performed passions and affects associated with femininity, dramatizing John Dowland’s ayres of weeping and Campion’s diverse portrayals of female characters. And female singers themselves adopted the speaking positions of jealous husbands, ambitious courtiers, chaste maidens, and adulterous wives, taking advantage of new opportunities for musical education and performance no longer exclusive to men. Throughout the ayre movement, portrayals of gender were caught between a series of cultural expectations, the preoccupations of poets and composers, and the corporealities that performers produced through their gestures, words, and sounds. Gender was not simply a theme that poets and composers manipulated to suit their expressive goals: even their choices of poems and written expressions of masculinity and femininity were influenced by the performance culture in which they were implicated.

The treatment of gender in books of ayres can be contextualized within the lyric miscellany tradition that includes Richard Tottel’s Songes and Sonetts (1557) and is characterized by doleful Petrarchan speakers.5 Books of ayres largely took over from other types of miscellanies, for a brief period, as the dominant means by which lyric poetry circulated in print. In this sense, songbooks can be compared with the many sonnet sequences written during the 1590s. Both sonnets and ayres were trends concentrated in a single decade of production (most songbooks were printed in the first decade of the seventeenth century). Both take an older continental convention (for books of ayres, a combination of French and Italian musical styles, including the air de cour from which they derive their name) and fashion it into a distinctively English genre. And both redirect Petrarchism to new ends, using the female body as a means of meditating on themes ranging from sovereign power to procreation to social order.6 The key difference is that, in books of ayres, female voices literally answer back. Books of ayres are unavoidably musical, making explicit the performative dimension of many early modern lyrics and treating gender as something more than an allusion or a theme.

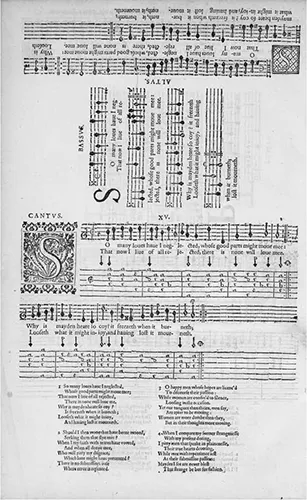

This tendency was made possible by the fact that books of ayres were specifically designed for household performance by amateurs, including women. Typically printed in “table book” folios, in which the main vocal part is printed above tablature for lute accompaniment while other parts are printed upside down or sideways, lute songbooks invite an intimate gathering around a single copy of a book (Figure 1.1). The music tends to be relatively straightforward and contained within a limited vocal range. Indeed, the songbooks followed upon the publication of several influential pedagogical books for aspiring singers and lutenists, including Adrian Le Roy’s A Briefe and Plaine Instruction to Set All Musicke of Eight Diuers Tunes in Tableture for the Lute (translated in 1568 and 1574), Thomas Morley’s A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke (1597), and William Barley’s A new Booke of Tabliture, Containing sundrie easie and familiar Instructions (1596). Together with John Dowland, who published his influential First Booke of Songes or Ayres in 1597, Barley helped set off the songbook “boom” with his instructional book emphasizing the appeal of lute music for amateurs, noting in his preface to the reader: “I have done it for their sakes which be learners in this Art and cannot have such recourse to teachers as they would.”7 Throughout the period, composers, including Dowland’s son Robert, continue to advertise the suitability of their ayres for all skill levels: “some I have purposely sorted to the capacitie of young practitioners, the rest by degrees are of greater depth and skill, so that like a carefull Confectionary, as neere as might be I have fitted my Banquet for all tastes.”8 Furthermore, as Daniel Fischlin has argued, ayres cultivate a “miniaturist aesthetic” of “introspection, solitude, and dialogical intimacy” that is suited to private or restricted performance settings.9

Fig. 1.1 Example of table book layout: Thomas Campion’s “So many loves have I neglected.” Thomas Campion, Two Bookes of Ayres (London, 1613), sig. L2v. This item is reproduced by permission of the Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

Because women were forbidden to perform in other, more public spaces, books of ayres offered a unique opportunity for them to participate in English musical culture. By the end of the sixteenth century, musical talent had become a mark of prestige among the nobility (and the aspiring nobility) and a desirable asset for marriageable women in particular, since it promised to impress suitors.10 Female music-making inspired condemnation as an unsuitable activity for young ladies that threatened to allure, corrupt, or effeminize men,11 but it was generally acceptable, and usually commendable, for women to sing and play string and keyboard instruments including lute, viol de gamba, and virginals, provided that they remained within a private domestic space.12 In this way, attitudes toward female musicians exemplify the more general paradoxes surrounding gender during the period, since a woman may have been lauded for musical eloquence in the household only to be scandalized by the same behavior in public. Thus Ophelia’s public entry (according to the first quarto of Hamlet) “playing on a lute” is a sign of her madness, but women including Lady Anne Clifford and Queen Elizabeth were painted holding the lute as a token of feminine decorum and social harmony.13 Men, too, were advised to restrict their musicianship to private leisure: Thomas Elyot and other writers on education emphasize that a gentleman should not play in “open profession,” when others might “beholde him in the similitude of a co[m]mon servant or minstrell,” but rather “secretely, for the refresshynge of his witte, whan he hath tyme of solace.”14 But women were liable to suffer a much more vehement reaction to public performance, including accusations of harlotry, and it would have been out of the question for a woman to be employed as a musician at court, in the Chapel Royal, or even as a common minstrel.15

Books of ayres are thus like “closet” drama, which enabled early modern women to read and possibly perform theatrical roles in domestic spaces, except that evidence of female singing and lute-playing is more direct.16 The majority of ayres are notated at the vocal range associated with the countertenor male voice; in the preface to his 1613 volume Campion suggests that an upper range actually defines the genre: “Treble tunes, which are with us commonly called Ayres, are but Tenors mounted eight Notes higher.”17 The countertenor, which stretched into alto and treble ranges, was fashionable throughout the period and commonly developed among male vocalists. Yet it is...