![]()

Chapter 1

Psychobiology of Musical Gesture: Innate Rhythm, Harmony and Melody in Movements of Narration

Colwyn Trevarthen, Jonathan Delafield-Butt and Benjaman Schögler

After the pleasures which arise from gratification of the bodily appetites, there seems to be none more natural to man than Music and Dancing. In the progress of art and improvement they are, perhaps, the first and earliest pleasures of his own invention; for those which arise from the gratification of the bodily appetites cannot be said to be his own invention. (Adam Smith 1982[1777]: 187)

Time and measure are to instrumental Music what order and method are to discourse; they break it into proper parts and divisions, by which we are enabled both to remember better what has gone before, and frequently to foresee somewhat of what is to come after: we frequently foresee the return of a period which we know must correspond to another which we remember to have gone before; and according to the saying of an ancient philosopher and musician, the enjoyment of Music arises partly from memory and partly from foresight. (Adam Smith (1982[1777]: 204)

Culture is activity of thought, and receptiveness to beauty and humane feeling. Scraps of information have nothing to do with it. (Alfred North Whitehead 1929)

In this chapter we explore the innate sense of animate time in movement – without this there is no dance, no music, no narrative, and no teaching and learning of cultural skills. We interrogate the measured ‘musicality’ of infants’ movements and their willing engagement with musical elements of other persons’ expressive gestures. These features of human natural history are still mysterious, but they are clearly of fundamental importance. They indicate the way we are built to act to express ideas and tell stories with our bodies, and out of which all manner of musical art is created, how our experience of the meaning of our actions is passed between persons, through communities and from generations to generation.

The communicative gestures of human bodies may become elaborately contrived, but they do not have to be trained to present the rhythm and harmony of what minds intend. Our movements communicate what our brains anticipate our bodies will do and how this will feel because others are sensitive to the essential control processes of our movements, which match their own. Gestures, whether seen, felt or heard, indicate the motivating force and coherence of central neural plans for immanent action in present circumstances. They have a desire to tell stories by mimesis, and may allude to imaginary adventures over a scale of intervals of time, in rhythmic units from present moments to lifetimes measured in the brain. They can imitate thoughts about circumstances that lie away from present practical reality somewhere in the imagined future or the remembered past, assuming responsibility for a sensible fantasy that wants to be shared. In this way music is heard as sounds of the human body moving reflectively and hopefully, with a sociable purpose that finds pride in the telling of ‘make believe’.

The Natural Process that Makes Music, and Makes it Communicative

Music moves us because we hear human intentions, thoughts and feelings moving in it, and because we appreciate their urgency and harmony. It excites motives and thoughts that animate our conscious acting and appraising of reality. It appeals to emotions that measure the effort and satisfactions, advantages and dangers of moving in intricate repetitive ways. Evidently a feeling for music is part of the adaptations of the human species for acting in a human-made world; part, too, of how cultural symbols and languages are fabricated and learned (Gratier & Trevarthen 2008; Kühl 2007).

Sensations in the body of the moving Self and its well-being, proprioceptive and visceral, are perceived as metaphors for effective action, feeling ‘how’ or ‘why’ the act is made without actually having to say ‘what’ the object is (Damasio 1999; Gallese & Lakoff 2005; Lakoff & Johnson 1980, 1999). When we hear another’s voice their intentions and affective qualities are powerfully conveyed because our organ of hearing is designed to appreciate the energy, grace and narrative purpose of mouths moving as human breathing is made to sound through the actions of delicately controlled vocal organs (Fonagy 2001). Vocalizations reflect the motives and effects of the whole body in action. We hear how inner and outer body parts may come into action in harmonious combination under the control of motives and experience, or fall into clumsy disorder. Thus we can cry out or sing gestures of hope and fear, of love and anger, peace and violence, moving one another with the power of the voice so we can participate in one another’s feelings (Panskepp & Trevarthen 2009).

Human hands are also gifted with the mimetic ability to accompany these vocal images of action (Kendon 1980, 1993), richly illustrating the messages of the voice in chains of action that may be sounded as melodies on musical instruments to accompany song, or take its place. Music and dance exhibit how we plan the moving of where to go and what to know, and they appeal immediately to the imaginations of others. They are poetry without words about roles for acting in community. They are the matter and energy that dramatists, composers and choreographers transform in the creation of what the philosopher Adam Smith (1982[1777]) calls the ‘imitative arts’, activities that express ‘pleasures of man’s own invention’.

Music communicates the mind’s essential coherence of purpose, a wilfulness that holds its elements in a narrative form through phenomenal, experienced, time (Malloch & Trevarthen 2009). Every gesture in music feels with the whole Self of a performer, an imaginary actor or dancer, whether the stepping body with its full weight and strong attitudes, or only the subtle flexions of a hand, or the lifts and falls that link tones of voice in melody with expressive movements of the eyes and face. The different parts share an intrinsic pulse and tones ordered in polyrhythmic sequences – harmonious or beautiful because they convey the making of well-formed thoughts and sensitively compounded feelings, or unharmonious and ugly, not because they are out of control, but because they struggle to keep hold of and rein in forces that would pull them to pieces. Every piece of music, even the smallest melody, is made with sociable purpose. That is what distinguishes a musical action from an action that is purely practical, to get something done.

Research on infants’ gestures and their sensitivity for responsive company reveals that these properties of the embodied human spirit, and the programme of their development in human company, are innate (Trevarthen 1986). It indicates, also, how music expresses an inborn human skill for cultural learning that seeks to know traditional stories in body movement. Human gestures are communicative, creative and inquisitive, seeking to imitate new forms.

Natural Causes and Functions of Gestures and Gesture Complexes

For this chapter we define a unit gesture as expression of intention by a single movement. Any body movement can be an expression with potential to communicate, but the expression most often meant when we speak of a human gesture is a movement of the hands. Single gestures do not ‘mean’ in isolation from meaningful situations and activities that are contrived with the intentions and awareness of the subjects that perform them. They are components of intentional plots – sequences or gesture complexes that express the flow and invention of movement and awareness in the mind. When gestures are defined as artificial symbols comparable to words they are said to derive meaning from the ‘context’ in which they are performed, but the context of any expression is not a static, or objective, state of affairs. A context of meanings, for all kinds of expression including symbols, is the field of intentions and awareness in which the expressions are generated. It is something psychologically invented.

It is important that all communicative gestures of animals – head bobbing and hand waving of lizards, singing of whales or nightingales, cries of migrating geese, squeaking of mice, grunts of baboons – are both self-regulatory (felt within the body or guided by interested subjective attention to objects and events in the world) and adapted for social communication, intersubjectively (Darwin 1872; Panksepp & Trevarthen 2009; Porges 2003; Rodriguez & Palacios 2007). They are for transmitting purposes and feelings through a community. They manifest intentions in forms that can be sensed by other individuals as signs or symptoms of the motives that generate them. They serve cooperative life, including adaptive engagements between species, be they predatory or mutually beneficial.

Human gestures function in the creation of a unique cultural world where motives are shared in narrations of movement expressive of inventions in thinking and acting – organized sequences of actions that convey original thoughts, intentions, imaginary or remembered experiences – that are made, not only with logical order to perform some action in the world, but with feeling for the drama of changing experience (Gratier & Trevarthen 2008). Gestural expressions, with their innate timing and combination in narrations, are the foundation for learning all the forms and values of the elaborate cultural rituals and the conventions of art and language (Gentilucci & Corballis 2006). Their motive processes expressed in sound are the primary matter of music (Gritten & King 2006; Trevarthen 1999a).

Many kinds of movements of a person can communicate psychological or physiological experiences and purposes, and this has made for confusion in discussions by psychologists and linguists about what is a gesture (Hatten 2006). Attention focused on an a priori categorization of the multifarious special uses or products of gestures, according to contrived grammatical and semantic rules and symbols, leaves the motivating source of timing, form and feeling obscure. The movements and sounds we make with our bodies, both when reflecting to ourselves on experience or in live dialogue with others, are not just learned conventions. They arise as spontaneous acts of vitality, more or less artfully contrived, all of which reveal motive states and experiences of the Self that others may appreciate.

Works of art require the intimate cultivation of gestures as more or less elaborate confections of ritual and technique that enable a community to share identified beliefs, dreams and memories. They are coloured by innate aesthetic and moral emotions that regulate their motive source, and, as Whitehead (1929) says, that guide cultural thinking. Musical art cultivates gestures of the voice, or of sound made by skilled action of hands or bodies on resonant matter. While it may be compared, in its basic social functions, to sound-making activities by which animals enliven their encounters and sustain relationships in community, human music has much more ambitious narrative content and make-believe.

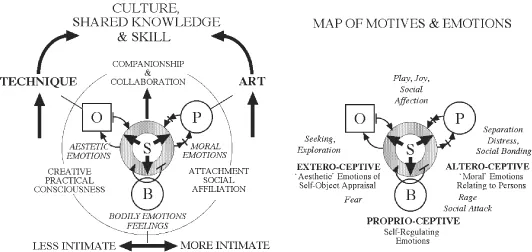

Gestures are embodied intentional actions that signal three kinds of moving experience, in three different domains of consciousness. They can sense, show and regulate the state of the body of the person who makes them; they can manifest and direct interests to the objective world of physical ‘things’; and they can convey the purposes of communication with other persons, or any combination of these three (Figure 1.1). Every gesture is an outward expression of the vitality of the subject’s dynamic ‘state of mind’’, the feeling of how motive energy flows in the muscles of the body through a controlled time. It shows the purpose or project that prompts moving in that way and with that rhythm and effort. By a unique process of sympathetic resonance of motives and narratives of feeling, which need not be regulated by any conscious intention to communicate or any technique of rational organization, it can function to transmit vitality states or motives to another or to many others, intersubjectively, mediating companionship in agency.

Figure 1.1 Left: Three ways in which the Self (S) regulates intentions to move: within the body (B), in accommodation to objects (O) and in communication with persons (P). All three participate in the collaborations of companionship and shared meaning. Right: A map of motives and emotions – affects regulating intentions of the Self in different circumstances (after Panksepp 1998; Panksepp & Trevarthen 2009)

Contemporary brain science is helping us realize that intersubjective communication of intentions and emotions is part of our cerebral physiology (Gallese 2003; Gallese, Keysers & Rizzolatti 2004). Nevertheless, while it is clear that gestures function by engaging brain activity between persons, the primitive ‘generative’ process of sympathy, by which the motive and affective regulation of a movement in one embodied animal mind may engage with and affect the stream of intentions and feelings of mind and body in another individual, remains a mystery. We cannot explain how the gestural motive evolving in the brain of one being becomes a message that motivates another brain to pick up the process in a particular imitative way. Presumably it is by sensitivity to parameters of the control processes of our individual self-awareness, revealed by our moving bodies, that others become aware of that control and can participate in it.

In social life, the distinction between a movement or posture made ‘in communication’ and therefore a ‘gesture’, as opposed to one not intended for communication but entirely for individual purposes is unclear. It would appear to depend on the abilities of one individual to ‘feel with’ the motives that cause and direct any kind of action of the other. The process will gain direction and subtlety by learning in real-life communication, but this learning itself would appear to require adaptations for an innate intersubjective awareness that is active from the start of life with others (Beebe et al. 2005; Trevarthen 1987, 1998, 1999b; Zlatev et al. 2008).

A Theory of Expressive Movement: Levels of Regulation of Action

Motives give form and prospective control to movements, and emotions expressed in the tempi and qualities of movement are the regulators of the power and selectivity of motives. They carry evidence of the Self-regulated flow of energy in motor actions – of the proprio-ceptive regulation of the force and grace of moving, with prospective emotional assessment of risks and benefits. Movements must be adjusted to the external realities of the environment and therefore have to submit to extero-ceptive regulation of awareness of the configurations, motions and qualities of places and things. Motives and emotions are communicated between persons by an immediate sympathetic perception of their dynamic features – i.e. by assimilation of their proprioceptive feelings and exteroceptive interests by others into altero-ceptive regulation (Figure 1.1). This interpersonal regulation in the moment of communicating opens the way to further and more enduring levels or fields of regulation for actions, their manners and goals. What may be called socio-ceptive regulation of actions in relationships and communities leads to development of collective ways of behaving that become an environment of common understandings or a ‘habitus’ for cooperative life. Further elaboration of conventional customs, rituals, structures, tools, institutions, symbols and beliefs, and languages, gives cooperative works trans-generational meaning in an iconoceptive regulation of human cultural behaviour.

These distinctions of how actions are regulated for different purposes are important in the sharing of the creativity and exuberance of art, and in any educational or therapeutic practice designed to strengthen the participation of persons, children or adults, in affectionate and meaningful relationships with others. All art and therapy depends on respect for altero-ceptive and ‘higher’, more contrived forms of regulation. When a learner experiences difficulties in understanding and practice of a culturally valued behaviour, such as appropriate social manners, speech or performance of sport or music, it is not sufficient to identify a fault and try to treat it as if the affected individual were a physical system or a form of life without human sympathies. ‘Intent participation’ in new experience with a teacher is required (Rogoff 2003).

Because human minds naturally seek ...