![]()

Part I

The Music of Mañjuśrī’s Mountain

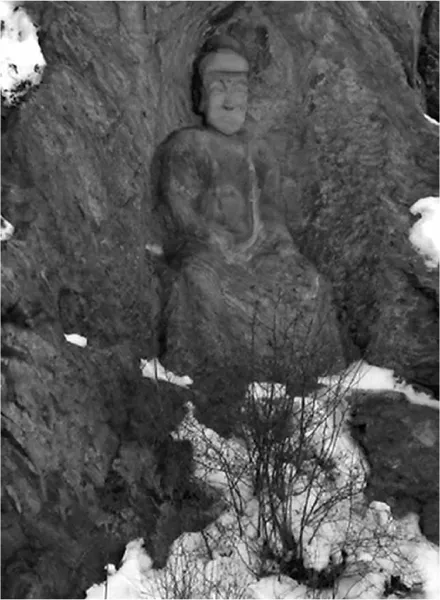

Figure A The Buddha with a new face

Most days during my field research, I would walk past a Buddha carved into a rock face on the southwest edge of Taihuai. One day, I decided to investigate the image from close up, and I found that the Buddha’s face had been chiseled off, and subsequently replaced with one made of concrete. The new face looked a bit like the product of a primary school art class; the lips had been rolled out like two clay snakes and placed in an impetuous pout, the eyebrows were raised in a look of surprised condescension, and the Buddha’s topknot had sagged forward, creating an effect reminiscent of the American televangelist’s bouffant.

This Buddha’s literal defacement and reconstruction demonstrate that recent decades have not been kind to the material culture and religious practices of Wutaishan; the area has been an epicenter of civil war and Japanese occupation, with rival factions converting monastic buildings into armories and forts, it has suffered greatly as Land Reform stripped monasteries of their landholdings and forced local people to make a living by farming the inhospitable mountainous soil rather than by catering to pilgrims, and it has borne the brunt of the destructive impulses of the Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution. I suspect it was Red Guards who chipped away this Buddha’s original face. These difficulties have not destroyed Buddhist practices at Wutaishan. Just as this Buddha has a new, if somewhat amateurish face, so too have ritual and musical practices been re-imagined and recreated as they recover from twentieth-century disruptions. We might suspect that the area’s Buddhist music, like this statue, is not what it once was, but its continued existence speaks to the tenacity of Chinese Buddhism in the face of daunting challenges.

![]()

Chapter 1

A History of Wutaishan Buddhist Music

The survival of Wutaishan’s Buddhist music speaks to the practice’s value as a local and religious tradition and to its remarkable adaptability in the face of drastically changing political, religious and economic circumstances. While the origins of the practice of including shengguan music in monastic ritual at Wutaishan are unknown, it seems to have survived for at least 500 years, pausing for only a few decades during the tumultuous twentieth century.

A Brief History of Wutaishan

The name “Wutaishan” translates as “Five-Terrace Mountain,” in reference to the five flat-topped peaks that dot the area. One of China’s four holy Buddhist mountain areas, Wutaishan lies in north Shanxi Province, 400 kilometers west southwest of Beijing. Some sources claim that the earliest Buddhist temple at Wutaishan, Lingjiu feng, named for the area’s purported resemblance to India’s Vulture Peak, was founded in 68 CE.1 This is just one year after the construction of China’s first Buddhist monastery, Baima si in Henan Province. While there is little evidence to support the existence of a monastery in Wutaishan at such an early date, it is clear that monasteries had been founded in the area by the time of the Northern Wei dynasty in the fifth and sixth centuries.2 Monastery construction is thought to have peaked in Wutaishan during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), when the number of such institutions reached about 360.3

Wutaishan is considered the earthly abode of the bodhisattva of wisdom Wenshu, or Mañjuśrī. This idea comes from the Buddhist sutra Huayan jing, or Avataṃsaka Sutra, which states, “In the northeast there is a place called Cool, Clear Mountain, where enlightening beings have lived since ancient times; now there is an enlightening being there named Mañjuśrī, with a following of ten thousand enlightening beings, always expounding the Teaching.”4 This sutra was first fully translated into Chinese in the fifth century, and soon thereafter Wutaishan’s identification as Wenshu’s Cool, Clear Mountain made the region an important pilgrimage site for Buddhists from all over East and Central Asia.5 From the time of the Northern Wei Dynasty (438–532 CE), Wutaishan developed as a center for the study of the Huayan jing, which focuses largely on the teachings of Wenshu. Some Wutaishan monks have undertaken dramatic feats of personal sacrifice to demonstrate their devotion to the study and promulgation of this sutra. In the 1940s, local monk Yinxiu wrote out all eighty-one fascicles of the Huayan jing with blood from his tongue.6

Pilgrims to Wutaishan report experiencing wondrous visions among the mountains. The eighth-century Buddhist monk Fazhao had a detailed vision of a grand monastery, along with the bodhisattvas Wenshu and Puxian (Samantabhadra) when he first visited the area, and his vision led him to construct Zhulin si.7 In the eleventh century, scholar and lay Buddhist Chang Shang-Ying reported seeing golden bridges, golden staircases, rays of light, and, floating in the sky northwest of the central terrace, “a world of blue crystal teeming with legions of bodhisattvas, sumptuous towers and halls, jewellike mountains and forests, ornate pennants and canopies, jeweled terraces and thrones, heavenly kings and arhats, lions and musk elephants, all arrayed in ineffable magnificence.”8

Wenshu is an important figure in Tibeto-Mongolian as well as Chinese Buddhism. Because of Wenshu’s vital role in Tibetan Tantrayana sects, and also due to the proximity of the area to Mongolian areas dominated by those sects, Wutaishan houses both Han Chinese and Tibeto-Mongolian Buddhist monasteries. Tibeto-Mongolian monasteries first appeared in Wutaishan in the seventeenth century.9 Many of these expanded in size and grandeur under Qing rule, since the Manchu emperors of that dynasty were adherents of Tibetan Buddhism.10

Monks and nuns in these imperially-funded monasteries performed large-scale rituals to ensure the well-being of the empire. Imperial support contributed to the grandiosity of Wutaishan’s monastic architecture, many of which feature the red-and-yellow color scheme of China’s royal palaces, as well as to a tendency for magnificent display in local rituals.

Wutaishan’s Local Chant Style

Buddhist ritual at Wutaishan traditionally involves unique local styles of both chant and instrumental music. Wutaishan’s chant, called by its practitioners the “Northern style,” is generally faster than the more common “Southern style,” and uses some unique local melodies. There are three basic types of chant in the “Northern” style: nian (recitation), song (solo incantation), and chang (singing). Recitation involves quick reading of scripture to a very simple two-pitch melody, to which most monks add ornamentation. This style can also be heard in monasteries in which the “Southern” style of chant is practiced, but in those monasteries it is usually performed at a slower tempo. Song is used only in certain funeral and calendrical rites at Wutaishan. In this style of chant, a single ritual leader recites text with no melodic or percussive accompaniment. Two lines of text are presented on a single breath, set to a sweeping arch-shaped melody. Local monks who continue this practice today pride themselves on their skill in performing lengthy passages in song style on a single breath. Monks sing hymns, gathas, and other songlike passages, and melodies vary among different regional traditions. It should be noted that only two of Wutaishan’s Han Chinese monasteries maintain the “Northern” style of chant. All monasteries other than Shuxiang si and Nanshan si use the more universal “Southern” style.11

A delightful origin myth, quite popular with Wutaishan tour guides and guidebooks, explains the development of the Northern style of Buddhist chant. During the Tang era, it is said, a monk named Fazhao began seeing a vision of a mountain temple each day in his porridge. The vision resembled the scenery of Wutaishan, so in 770 he traveled there to investigate. A white light led him to the site of his vision, a temple tucked away in a bamboo grove. Fazhao was obviously still caught up in his vision; no bamboo grows in Wutaishan.

Fazhao saw Wenshu sitting on a lotus throne inside the temple, and he asked the bodhisattva how one may become enlightened. Wenshu taught Fazhao how to recite the name of Amituofo, the Buddha of the Western Paradise (Sanskrit: Amitābha), in five different styles, assuring the monk that this would lead to rebirth in paradise and eventual enlightenment.12 This aligns with the tenets of Pure Land Buddhism, which call for practitioners to engage in simple chanting or visualization in order to attain rebirth in paradise and eventual enlightenment. Musicologist Xiao Yu quotes the Jingtu wuhui nianfo lü fashi yizan, which lists the five styles as, “First, recite “Namo Amituofo” on a single pitch in a slow tempo, second, recite “Namo Amituofo” with a rising pitch at a slow tempo, third recite “Namo Amituofo” at a tempo neither fast nor slow, fourth recite “Namo Amituofo” at a gradually increasing tempo, and fifth recite the four syllables “Amituofo” quickly while walking.”13 On the efficacy of these methods of reciting the Buddha’s name, Fazhao stated that, “These five forms of chanting proceed from the leisurely to the fast-paced, during the course of which one concentrates one’s thought wholly on the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha and abandons all other thoughts. When thought becomes no-thought, it is the door of non-duality of the Buddha. When sound becomes no-sound, it is absolute truth. Hence, practicing mindful recollection of the Buddha for the rest of your days, you will always be in accord with the nature of reality.”14 Fazhao calls the five styles of chant wuhui nianfo, and they purportedly comprise the basis for Wutaishan’s local chant style.

Miraculously, the emperor heard Fazhao chanting from the distant palace in Chang’an and asked one of his advisers to investigate. The adviser eventually followed the sound to Wutaishan and found Fazhao chanting in a hollow. Convinced that Fazhao had experienced an authentic enlightening vision, the emperor named him Buddhist master of the court and sponsored the building of a temple on the site of the master’s vision. This temple, completed in 796, is called Zhulin si (Bamboo Grove Monastery) in honor of Fazhao’s vision.

Fazhao’s wuhui nianfo gained international prominence as pilgrims flocked to Zhulin si, a center for Tiantai (or Tendai) Buddhism. Due to Fazhao’s popularity with the imperial court under the reigns of Emperor Daizong (762–79) and Emperor Dezong (780–805), wuhui nianfo also spread to a number of state-sponsored Pure Land cloisters in the capital and beyond. The Japanese pilgrim Ennin brought the practice back to Mount Hiei, a Tendai center near Kyoto after visiting Wutaishan in the mid ninth century.15 Unfortunately, with the mid ninth-century persecution of Buddhism under Emperor Wu, Fazhao’s two known treatises on his chant style were destroyed.16 It is unclear to what extent wuhui nianfo remains influential on the chant practices at Wutaishan and beyond; perhaps a close analysis of current practices at Pure Land centers in China and Japan will reveal evidence of the continuing influence of Fazhao’s teachings.

While a newly-rebuilt Zhulin si can be found today at Wutaishan, the nature of the connection between Fazhao’s wuhui nianfo and the local “Northern” style of chan...