- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

May Sinclair was a central figure in the modernist movement, whose contribution has long been underacknowledged. A woman of both modern and Victorian impulses, a popular novelist who also embraced modernist narrative techniques, Sinclair embodied the contradictions of her era. The contributors to this collection, the first on Sinclair's career and writings, examine these contradictions, tracing their evolution over the span of Sinclair's professional life as they provide insights into Sinclair's complex and enigmatic texts. In doing so, they engage with the cultural and literary phenomena Sinclair herself critiqued and influenced: the evolving literary marketplace, changing sexual and social mores, developments in the fields of psychology, the women's suffrage movement, and World War I. Sinclair not only had her finger on the pulse of the intellectual and social challenges of her time, but also she was connected through her writing with authors located in diverse regions of literary modernism's social web, including James Joyce, Ezra Pound, Ford Madox Ford, Charlotte Mew, and Dorothy Richardson. The volume is a crucial contribution to our understanding of the political, social, and literary currents of the modernist period.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART 1

May Sinclair and Literary Modernism

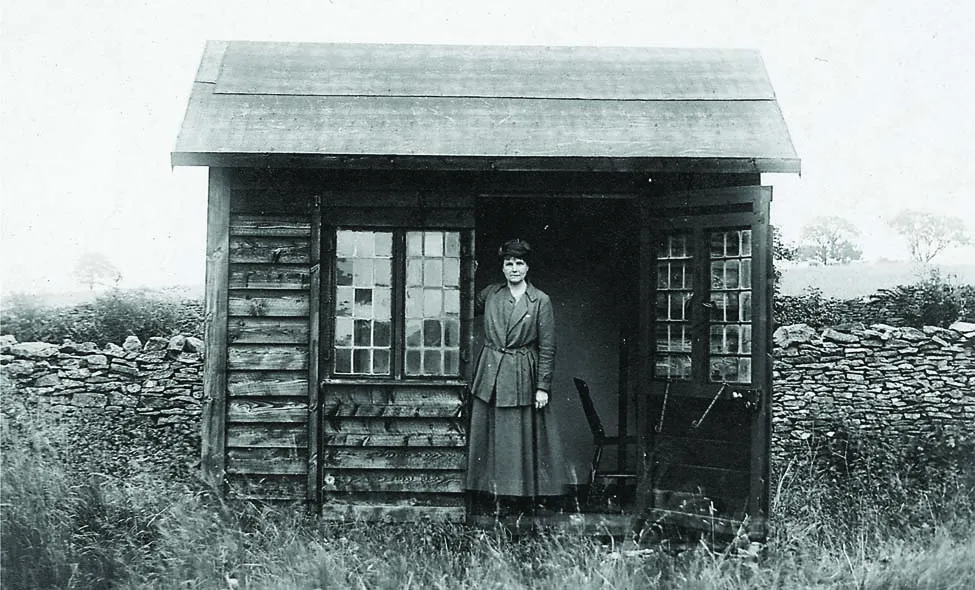

Figure 2 May Sinclair in front of her writing hut in Stow-on-the-Wold, 1920s.

Chapter 1

A Very “Un-English” English Writer: May Sinclair’s Early Reception in Europe

In the foreword to his 1928 two-volume survey English Literature of the Present Since 1870: Drama and the Novel, Austrian Professor Friedrich Wild comments on the recent explosion of English books in his country: “More than ever German translations of the titles of English novels glance at us from the shop windows, with plays by English authors performed in our theaters” (np). Other critics appear to have shared Wild’s anecdotal impression of the growing reach of literature from that land across the Channel. Whatever the reasons European readers found English books appealing, the 1920s and early 1930s spawned a wealth of literary surveys, essay collections, and monographs that promised readers of French and German a “guide book for … explorers in the realm of English fiction” (ix)—in the words prominent French critic and cultural minister Abel Chevalley used to describe his own 1921 survey The Modern English Novel.1 We might assume that the fates of English writers, once and for always, lay in the hands of critics in their own language. Yet this body of writing suggests that foreign critics also helped shape the careers of particular authors and the face of British modernism for new continental audiences. In the case of May Sinclair, the enthusiasm foreign intellectuals showed for her work did not preserve her reputation; however, their commentary is nonetheless important because it signals the breadth of her influence as a writer who helped modernism gain its first toehold in literary history.

One interesting aspect of continental reception is the effect of a time delay on an author’s standing. Sinclair’s reputation soared on the continent just as it had begun to drag in the United States and, especially, in England. This discrepancy may result from the fact that many continental critics were feasting on Mary Olivier (1919) and Life and Death of Harriett Frean (1922) for the first time in the mid-1920s, when the German publisher Tauchnitz had just made Sinclair’s later novels accessible to foreign audiences. Tauchnitz, which had since 1842 sold books in the original English language to continental readers, published eight of Sinclair’s works in quick succession between 1923 and 1927—all but the first coinciding with their publication year in England: Anne Severn and the Fieldings (1923), Uncanny Stories (1923), A Cure of Souls (1924), Arnold Waterlow: A Life(1924), The Rector of Wyck (1925), Far End (1926), The Allinghams (1927), and History of Anthony Waring (1927) (Schlösser 490). While this list seems impressive, it does not include what Sinclair’s English-speaking contemporaries often listed as her best works: The Three Sisters (1914), Mary Olivier, and Life and Death of Harriett Frean. Yet articles and surveys suggest that enough foreign reviewers had gotten hold of and heartily endorsed these three earlier works by the time the Tauchnitz series was reviewed that a buzz was in the air about Sinclair: this passionate, well-educated, and versatile writer who could debate philosophy or spin meaningful stories; this innovator in form and content, linked elbow in elbow with Dorothy Richardson, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, and D.H. Lawrence. Many European critics thus view her later novels, which English-speaking reviewers often branded as more traditional, and even pallid, through this glowing haze, ready to see their positive impressions of Sinclair confirmed.

The continent also offered other benefits to Sinclair, as it had to some of her peers. In fact, in the years between the two World Wars especially, reviewers in French- and German-speaking countries often prided themselves on rolling out a better welcome mat to controversial English authors than their fellow citizens back home. To offer one of many examples, reviewer Wolf Zucker of the left-leaning journal The Literary World states with conviction in his 1930 obituary of Lawrence, “Thus is the continental assessment of Lawrence juster than in his homeland” (2).2 The continent did not simply offer cutting-edge English authors an additional market for their work, and thus, more money in their coffers; perhaps as important, it also provided an intellectual climate that was generally more receptive to the very innovations of style and content that had previously raised the hackles of English-speaking critics. Certainly, for authors such as Lawrence and Joyce, the continental market also made it possible for censored novels to see the light of day at all.

While Sinclair’s work was not embroiled in the same degree of controversy as either Lawrence’s or Joyce’s, she, too, was a writer often more embraced by continental than by English-speaking critics during her lifetime. Wild suggests one reason for this when he applauds Sinclair’s judgment and her free, open-minded handling of psychological problems in her work, adding, as if an afterthought, that critics from her own country often object to the very aspects of her work that he finds most rewarding. “But,” he clarifies, “her work isn’t experienced by British critics as actually English, but instead as a foreign import,” because of her interest in psychological methods and Freudian theories (288).3 One does not have to throw a stone too far to find reviews of Sinclair’s work that bear out Wild’s theory. Quite famously, Lady Eleanor Cecil publicly castigated Sinclair in 1907 for trying to bolster sales for her novel The Helpmate by imitating a licentious French view that encouraged marital infidelity (Raitt 103). Cecil carps that Sinclair has “[taken] a few hints from Paris” and succumbed to the seductive new credo: “Be bold, be daring, be unconventional—above all, be Continental” (Cecil 587). An anonymous 1919 review of Mary Olivier in the Times Literary Supplement complains, in equally melodramatic fashion, not of Sinclair’s libertinism, but of her extreme pessimism, suggesting that she had imbibed too much of the culture that had produced Schopenhauer and Nietzsche:

She revenges herself with an unholy joy by … making us share by her acrid power of realization all the bitter moments. … Such dreary mockery, such terrible acuity of perception, are dangerous, double-edged weapons. … If this be the approved German treatment for such terrifying morbidity, we must say we prefer the old-fashioned Burton (“Be not solitary, be not idle”) or Johnson. Thwarted lives cannot safely dwell upon such a depressing view of the pitifulness of all life and endeavour. (324)

To understand how and why foreign critics parted company with their English and American counterparts, it is important to sketch first the response of English-speaking critics who had earlier access to Sinclair’s writings.4 Certainly, many showered praise on Sinclair over the span of her career, as other essays in this collection will also attest. Yet since negative commentaries weakened Sinclair’s reputation over time, it is perhaps most important to see how continental critics responded to criticisms, rather than acclaim, from the English-speaking arena. We might start by saying that, even at the height of her career, Sinclair would have won the Critic’s Choice almost-but-not-quite award for her literary innovations across 30 years of novel-writing. For example, an anonymous review in the Times Literary Supplement in 1907 characterizes The Helpmate as “fine, sincere, and fearless,” yet tempers this praise with the judgment that the novel places its author “very little below” the top rank of living novelists (269). In a similar move, Martin Armstrong’s 1923 review of Sinclair’s Uncanny Stories in The Spectator concludes, “The book as a whole, in fact, does not represent Miss Sinclair at her best. But Miss Sinclair, after all, is a fine artist: her second-best is infinitely superior to the average novelist’s best” (429). Compton Mackenzie’s 1933 memoir more harshly determines, “Although she has left behind nothing but a series of failures, her failures were of greater value to English literature than many of other people’s successes” (213–4).

Such backhanded compliments linger awkwardly in the air, leaving behind an impression of Sinclair as a child who has not quite lived up to parental expectations. Surveying these responses from the 1910s on, beginning when Sinclair more overtly defended and pursued stylistic experimentation, the following major criticisms of her work emerge: she has become obsessed by innovations and is a slave to trends; her work seems too intellectual, with her use of technique and theory jutting too obviously into her fiction, interfering with readers’ ability to feel for her characters; and finally, she has not been enough of a woman of the world, so to speak, to write convincingly about the sexual issues and dilemmas that are centerpieces of her works.

To address the first of these points, perhaps the English and American sense of Sinclair “almost always” measuring up to either her own best or that of her contemporaries exacerbated their confusion over her intentions in pursuing formal innovations. Where was the real Sinclair, some seemed to ask, in this ever-widening gyre of literary exhibitionism? In his Some English Storytellers (1912), most obviously, Frederic Taber Cooper grants Sinclair a chapter because of his nostalgia for the Divine Fire; yet he expresses great indignation at what he sees as too much evolution in her work:

… the difficulty which must be faced in attempting to write a critical estimate of the work of May Sinclair, considered as a whole, is that this is precisely the way in which it refuses to be considered. Her novels are hopelessly, irremediably incommensurate; they have no common denominator; they reveal nothing in the way of a logical progression, of mental or spiritual growth from book to book, from theme to theme. (252)

Conversely, A. St. John Adcock devotes half of a chapter to Sinclair in his Gods of Modern Grub Street (1923), in which he paints her risk-taking as evidence of her integrity: “she has never like so many of the successful settled down to run in a groove; she does not repeat herself. She has not accepted ready-made formulas of art but has been continually reaching out for new ways of advance” (279). Yet as he continues, one can see how even his praise might plant the seed of suspicion in other readers about Sinclair’s relationship to younger innovators:

She was quick to see virtue in the literary method of James Joyce and Dorothy Richardson and the possibilities inherent in the novel which should look on everything through the consciousness of a single one of its characters, and proclaimed it as the type of novel that would have a future. She may not have convinced us of this when she applied the method in the ejaculatory, minutely detailed “Mary Olivier,” but its maturer development in “Harriet Frean” [sic] demonstrated that it was a manner which could be used with supreme effectiveness. (279)

Even through the lines of Adcock’s esteem, it is easy to absorb the message that Sinclair is an opportunist who imitated younger writers, just needing a round of practice to get it right.

The question of whether Sinclair created new trends or simply copied them is one that haunted her beginning with the 1910s, when her work was held up against the explosion of innovations in literary style and content in that decade. In somewhat catty fashion, Louise Collier Willcox describes Sinclair in a 1923 review of Uncanny Stories for the New York Bookman as a writer who has latched on to the “most experimental and unstable circle of ‘les Jeunes,’ obsessed by Freudian speculations, symbolist, uncapitalized poetry and dadaist painting” (574). In fact, Willcox claims, Sinclair “is so up to date that a bookworm one hundred years from now will be able to date her books easily from internal evidence (574). In The Novel in English (1931), Grant Knight similarly concludes that Sinclair has been “too ready to absorb current fads and theories” (346).

Yet critics overall were not content to rest with such general statements. Instead, speculations about whether and whom Sinclair copied pass, like so many tennis balls, back and forth from those who endorse Sinclair as an innovator to those who stamp her as a literary cradle-robber. With great tact and fairness, Babette Deutsch, Dorothy Scarborough, and Una Hunt suggest similarities between the techniques of Sinclair and Richardson, raising questions about who had developed the stream-of-consciousness technique and which writer used it more successfully. To offer one example, in a 1922 article for the New Republic, Hunt discusses the recent “fashion for reviewers to attribute these recent developments of Miss Sinclair to the influence of Dorothy Richardson. Why is it not rather true that they are both of them women who are profoundly sensitive to the influences of the day, completely courageous and of unswerving honesty?” (261). However, the bulk of such criticisms strike a shriller tone. In a 1922 article for The Literary Digest International Book Review, Gertrude Atherton favors Sinclair over Richardson, and so faults Sinclair for her “psychoanalysis obsession,” and the “Dorothy Richardson blight” which has “done her the most harm” (11). Clarifying, she adds, “women of real talent, like May Sinclair, who should be too independent to imitate anybody, have nearly been ruined by her [Richardson]” (11). In The Dial in 1922, Raymond Mortimer more snidely remarks, “Whenever a new book by Miss Sinclair appears, we wonder what it will be like this time; or rather whom. … Indeed, when a new author, or still more a new authoress wins our admiration by an innovation in method, Miss Sinclair always wants to show us that she can do it herself just as well. In Mary Olivier she did a Dorothy Richardson. This time it is a Katherine Mansfield” (533). On a more positive note, Vivian Shaw notes that Anne Severn and the Fieldings is in the mode of Lawrence but “in theme far more definite and far more extended than the work Mr. Lawrence has recently done” (197–8). Finally, in a review of Far End in 1926, Frances Newman includes the off-hand comment that the main character is a novelist “who apparently invented the stream of consciousness literary method instead of copying it from Dorothy Richardson” (228)—implying that Sinclair has used her protagonist to advertise her own real-world status as a literary inventor.5

A second critique of Sinclair’s wr...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- May Sinclair

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Notes on Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction May Sinclair: Moving Towards the Modern

- Part 1 May Sinclair and Literary Modernism

- Part 2 May Sinclair and the Modern World

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access May Sinclair by Michele K. Troy, Andrew J. Kunka in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.