![]()

Chapter 1

Post-communist Political Systems and Media Freedom and Independence

Karol Jakubowicz

Introduction

In view of the stated intention of most post-communist countries to transform into democratic systems, democratic theory and the body of work on the role of the media in democracy would appear to provide the most appropriate framework of comparative analysis of the development of media systems in particular countries of the region, especially as regards freedom and independence of the media. Over the past 20 years – and in many cases, for much longer – the populations of those countries have striven for democracy (Tanase 1999). Despite some caveats (Khakee 2002), the process of democratization and consolidation of media freedom and independence are seen as mutually reinforcing (Coricelli 2007, Faust 2007). Given that democracy is based on the free exchange of ideas, it is clear that the media are necessarily constitutive of any adequate contemporary theory of political democracy (Sparks 1995).

Of course, the relationship is neither obvious nor simple (Jakubowicz 2005, Mughan and Gunther 2000) and media organizations may not share this normative view of their own role in democracy. Nevertheless, it seems feasible to suggest that the extent of media independence and freedom in the region will be closely related to the extent of democratic consolidation. In other words, the media are an element of democracy and their freedom and independence will flourish as democracy flourishes. This general approach finds support in the work of Hallin and Mancini (2004), where analysis of the interplay between political systems (especially in the context of the maturation and consolidation of democracy) and media systems forms part of the general framework of analysis. Of course, they originally did not consider post-communist countries, but later stated that the polarized pluralist system might be closest to what is happening in the region (Hallin and Mancini 2009). While there is a clear need to go beyond the general Hallin and Mancini approach in other areas, this does not appear to be the case as far as political determinants of media systems are concerned. However, the intention here is to offer a more in-depth and nuanced analysis of political factors that have played a major, one could even say decisive role in shaping media systems in post-communist countries. It has been said that there are as many processes of post-communist transformation as there are post-communist countries. While shared general trends can be found, the important thing is to abandon the simplistic view of Central and Eastern Europe as a homogeneous grouping of countries and develop tools of identifying the specific circumstances of each country.

The effectiveness of the media’s influence on society depends to a large extent on the congruence of their impact with the larger process of political change unfolding in society. The media may and do affect political developments, but at the same time their impact is predicated on the existence of favourable political conditions without which they could not perform that function. To express this differently, the relationship between socio-political factors and media systems is one of non-equivalent or asymmetrical interdependence (cf. Jakubowicz 2007).

Below we will seek to verify this general hypothesis, and use it explain the divergent levels of media freedom and independence in the region. More specifically, our aim is three-fold. First, we will demonstrate that the scope of political and administrative control over the media depends on whether a country is democratic, semi-democratic, or autocratic. As we move along this continuum, the policy and legal framework will allow fewer and fewer media sectors and outlets to acquire legal and ownership status putting them outside state and/or political control. Second, we will show that specific institutional solutions adopted at the level of the political system are likely to be replicated at the level of the media. This is particularly evident in the broadcasting sector, where the regulatory authorities are a direct extension of the political power structure: their composition is determined by the type of the executive structure and the type of the electoral system. Third, we intend to demonstrate that the extent of media freedom and independence depends crucially on the behaviour and normative attitudes among the political elites, specifically on their attitudes to democratic values and behaviour vis-à-vis democratic institutions. As we will show, the threats to media freedom and independence in the region often stem not from a lack of adequate institutions and legislation, but rather from the fact that political elites and civil society actors alike consider it to be their right to use the media to further their goals. Journalists themselves are often no better; they are convinced their role is one of social leaders, called upon to promote the political views or forces they personally support.

This brings us to a key point, namely that the extent of media freedom and independence cannot be explained by reference to political systems alone. Rather, the functioning of both the political and the media system is crucially dependent on cultural factors such as the prevailing attitudes, values and ensuing behavioural patterns. Due to the key role cultural factors play in determining the form and functioning of political systems in post-communist states, we felt it necessary to incorporate this dimension also in our discussion. We should also add that analysts of the Central and Eastern European media scene point often point to the role of proprietors and their business interests, and generally to market forces, as a dominant force in shaping the media system (Jakubowicz and Sükösd 2008). It is undisputable that these economic factors also have the effect of curtailing journalistic and editorial freedom and independence.

The chapter starts by outlining the theoretical and analytical framework for the examination of relationships between democratization and media freedom. The rest of the chapter is divided into three sections, each of which tackles one of the three key propositions outlined above. Each of the sections starts by examining the structure and dynamics of the various political systems across the region, and then goes on to demonstrate how and to what extent these are replicated at the level of media systems.

Democratization and Media Freedom: The Analytical Framework

Some scholars maintain that all that is needed to define democracy is a ‘realistic and restricted definition’ of a democratic regime, consisting of ‘fair and institutionalized elections, jointly with some surrounding … political freedoms’ (O’Donnell 2002: 16). However, in the context of Central and Eastern Europe – and also more generally – it would in our opinion be a mistake to yield ‘the fallacy of electoralism’ (Diamond 2008). Democracy is not achieved through elections alone1 (Landman 2008). Munck (1996: 5–6) contends – correctly, in our view – that the institutional systems and procedural rules of democracy structure and shape the conduct of politics only inasmuch as actors accept or comply with these rules. The experience of Central and Eastern Europe suggests that both institutional and cultural approaches are needed to understand, and indeed to plan and implement, systemic transformation.

Successful consolidation of democracy ultimately depends on the institutionalization of new rules and values (see Diamond 1997, Morawski 1998, 2001, Sztompka 1999, 2000) and therefore on cultural factors, which often affect the process of creation of the rules and institutions of democracy and account for their proper use or abuse. Generally, they are subsumed under the term ‘civic/political/democratic culture’ (Dahlgren 1995, Paletz and Lipinski 1994). Political culture is one of the ‘key explanatory factors’ in understanding transitions (Wiarda 2001). It largely determines how individuals and the society act and react politically and so whether the society is able to maintain and operate a viable and enduring constitutional democratic system of government, or whether the society must choose between authoritarianism and domestic disorder (see also Linz and Stepan 1996, Offe 1997). It is therefore important to analyse the process of democratic consolidation not only in terms of its institutional dimensions, but also in terms of its behavioural and attitudinal dimensions (see e.g., Bajomi-Lázár 2008).

We propose this approach because we believe that it is precisely the cultural/attitudinal element of democracy that will determine whether or not democratic institutions will be created and whether they will be designed to be functional or dysfunctional in terms of the operation of democracy (institutional dimension) and how they will be used, or perhaps abused (behavioural dimension).

Democracy and Media Freedom in Post-Communist Countries: Between Democracy and Autocracy

A full examination of democratic development (or otherwise) in post-communist countries would require, in line with the path-dependency approach, an analysis of the process of transition, the outcome of this process of transition, and the process of consolidation (and, indeed, non-consolidation and deconsolidation) of democracy. According to Page (2006: 89), path dependence ‘requires a build-up of behavioural routines, social connections, or cognitive structures around an institution’. For reasons of space, however, we will need to leave the process of transition involved in the collapse of the communist system largely out of consideration (however crucially important it is in determining what happened afterwards) and begin with the outcome of transition.

With the jury still out on the final result of transition, any neat and tidy classifications of countries with respect to their level of democratization are bound to be elusive. Nevertheless, it is possible to divide post-communist countries into three broad, partly overlapping groups: democratic, semidemocratic and autocratic (Ekiert et al. 2007). Each of these is of course to be treated as an ideal type: most individual post-communist countries will not conform neatly to one type only, but will constitute hybrid systems.2 We might also want to think of many of the countries in question as featuring different political sequencing or as being at different stages of a democratization dynamic and thus occupying different locations on a continuum (Bunce 1999), with the possibility of moving ‘forward’ or ‘backsliding’. Indeed, some populist political forces in democratic post-communist countries have expressed impatience with the checks and balances that liberal democracy imposes on the authorities, showing interest in the system of ‘electoral democracy’ (as giving the majority returned to power a mandate to act without regard for the views of the minority).

According to Ekiert et al. (2007), the first group of democratic countries comprises successful countries where the process of democratic consolidation and the progress of economic reforms are well advanced, especially those that have joined the European Union. This group now also includes some of the countries which followed the ‘Mediterranean model of transition’ (Pusić 2000): Romania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Serbia and Albania. Having failed ‘in the first round’ to establish democracy in 1989 and 1990, they initially ended up with authoritarian or semi-authoritarian systems. The ‘second transition’ came a few years later and was needed to introduce the missing institutions of democracy and to promote both attitudinal and behavioural dimensions of democracy.

Then, there is a gray ‘in between’ zone, inhabited by countries oscillating between a semi-democratic and semi-authoritarian system. This, in turn, encompasses countries which experienced the ‘second wave’ of transitions in Central and Eastern Europe, sometimes also known as ‘colour revolutions’ in Georgia, Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan. They were, however, less successful in creating stable democratic systems than in some of the other countries (McFaul 2005, Way 2008). Some countries in this group were, or still are, ‘stuck in the stage of inter-regime competition’ (Bunce 1999: 242), unable to develop a clearly new political identity. A consequence of this was sometimes violent conflict (as in Tajikistan, Georgia and Bosnia); sometimes it gave rise to regimes that closely resembled their socialist predecessors, as in Belarus or much of Central Asia; and sometimes it produced hybrid regimes that married in haphazard fashion aspects of a liberal order with those of the state socialist past, as in Ukraine. Russia could be seen as another example of this phenomenon (Sestanovich 2004).

Finally, post-communist countries include authoritarian regimes that differ from communist dictatorship in some respects but consistently deny their citizens fundamental political freedoms and routinely violate human rights. In such countries (Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Belarus) initial political openings have clearly failed and authoritarian regimes have resolidified (Carothers 2002).

It is clear that most of the ‘transitional countries’, including the relatively successful ones, suffer from serious democratic deficits: poor representation of citizens’ interests, low levels of political participation beyond voting, frequent abuse of the law by government officials, elections of uncertain legitimacy, very low levels of public confidence in state institutions, and persistently poor institutional performance by the state. Nevertheless, post-communist countries clearly vary in the extent to which they were able to consolidate elements of democracy and the three-fold typology proposed above corresponds to some of the key features of media freedom and independence in these countries.

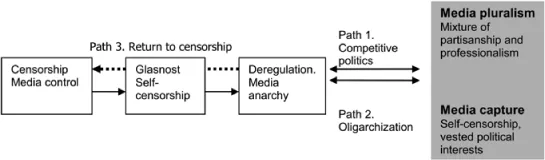

The relationship and interdependence between political development and the media is the subject of an extensive body of work (Bajomi-Lázár and Hegedűs 2001, Jakubowicz 2005). Change in the media in post-communist countries was expected to mirror the general process of democratic development and create an ‘enabling environment’ (Price and Krug 2000) for media freedom and independence. Indeed, media freedom and independence is higher in the democratic countries and progressively lower in semi-democratic and semi-authoritarian and authoritarian countries. Competitive politics and media pluralism prevail in the group of democratic countries; oligarchization and media capture in the semi-democratic/semi-authoritarian countries, and there has been a return to strict censorship (and no media independence) in the outright dictatorships. That this is indeed so, and that backsliding can happen also in this area, is suggested by Mungiu-Pippidi’s (2008: 91) view of the three paths of media evolution in post-communist countries, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Divergent paths from communist media control

Source: Mungiu-Pippidi 2008: 91 Reproduced with permission

We will demonstrate the relationship and interdependence between political development and the media by looking at two aspects: media ownership and general media policy orientations.

Media Ownership

If de-monopolization of the media was the first and fundamental goal of media change, then one criterion for assessing the degree of change is the diversity and pluriformity of media outlets, as well as forms and diversity of ownership. The first indicator is, of course, the existence of privately-owned media. In autocr...