This is a test

- 228 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Memories of Cities is a collection of essays that explore different ways of writing about the political and economic history of the built environment. Drawing upon fiction and non-fiction, and illustrated by original photographs, the essays employ a variety of narrative forms including memoirs, letters, and diary entries. They take the reader on a journey to cities such as Glasgow, Paris, Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Marseille, laying bare the contradictions of capitalist architectural and urban development, whilst simultaneously revealing alternative visions of how buildings and cities might be produced and organised.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Memories of Cities by Jonathan Charley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Glimmer of Other Worlds: Questions on Alternative Architectural Practice

INTRODUCTION

‘The Glimmer of Other Worlds’ was prompted by my experiences as a teacher attempting to explain to students what the idea of an alternative to capitalist building production might mean. It struck me that one way to address this was to ask a series of questions that are typical of the kind I have received over the years. In effect, it is an architectural and political manifesto that addresses a specific politically engaged meaning of alternative practice understood as anti-capitalist resistance. More broadly, it summarises ideas that I have been preoccupied with ever since I first left architecture school in 1980 and was lucky enough to find work in the firm Collective Building and Design. A cooperative – or more precisely, a self-management collective – I worked there for seven years. It was very much a formative experience and an apprenticeship in how to produce architecture in a different way. I left in part because of a desire to study more seriously the political economy of the built environment, and it was after completing a Masters at University College London that I went to Moscow for a year to begin my research into the history of Soviet architecture and construction. These questions then have been fermenting for a long time. As for the answers, these are works in progress. ‘The Glimmer of Other Worlds’ was first presented at the Alternate Currents Conference at the University of Sheffield in 2007, and published in the Architecture Research Quarterly (ARQ) in 2008.

1.1 ‘Architects of the world unite’. Marx in front of the Bolshoi Theatre

1

Can there be a greater spectacle or drama than the seizure of a city during the midst of a major protest or rebellion? St Petersburg, a metropolis framed by a skyline composed of glistening cupolas and belching toxic chimneys, sways with intoxicated expectation that a rent in time is about to appear. The cobbles crack with the sound of falling statues. Horses dangle from lifting bridges. Barricades mesh across streets. A panic-stricken government official searches for his nose and briefcase. Jealous civil servants, Francophile aristocrats, and vengeful generals are feverishly engaged in settling accounts, closing their shutters and securing safe passage out of the city.1

Q1. What is meant by the phrase alternative or alternative practice?

Alternative or alternate are politically neutral words that suggest something to do with notions of difference, opposites, or choice. Like any words, they acquire their meaning through context and association, such as in the expressions ‘the alternative society’, ‘alternative medicine’, or ‘alternative technology’. Here I want to deal with a very specific politically engaged meaning: alternative practice understood as anti-capitalist practice. By this I mean a way of doing things, including making buildings, which is not defined by capitalist imperatives and bourgeois morality. This has two aspects: first, in the sense of resisting the environmentally damaging and socially destructive aspects of capitalist urban development; second, in terms of engaging with embryonic post-capitalist forms of architectural and building production.

2

Murderous young men and women are hopping over the walls of back courts and thousands of subterranean proletarians with molten metal teeth pour out of the yards and factories, all of them searching for redemption. It is a perfect stage set for the outbreak of a revolution, its illuminated enlightenment boulevards poised over rat-infested basements. Till the moment before the cannon roars it continues to parade its cathedrals, boulevards and illustrious terraces with a Potemkin-like contempt for the rest of the city. The flâneur, the prince, the banker, and the priest cannot believe that the history of their fundamentally implausible city has entered a new phase in which they will be relegated to bit parts.

1.2 ‘The trickle-down theory of capitalist urbanisation’. Squatter camp, ‘Jardim de Paraguai’, São Paulo

Q2. But aren’t you swimming against the tide, against received wisdom?

We should always be sceptical of received wisdom, or in its rather more dangerous guise, common sense, which is often little more than ‘naturalised’ ideology. One example of this is the ‘common sense attitude’ that socialism is finished and that human civilisation ends with the combination of free-market capitalism and liberal parliamentary democracy. It is a conclusion reinforced by the ideological consensus sweeping across the political parties that neo-liberal economic theory is the panacea for the world’s ills.

Such ‘ideological common sense’ resembles a powerful virus that attacks the nervous system, destroying the powers of reason. Such is the germ’s strength that it induces a dream-like state of narcosis in the corridors of power. The rallying cries of dissent become ever more ethereal and faint. The memories of ideological disputes about alternative worlds or concepts of society that had dominated political life in earlier generations become increasingly opaque until they take their place alongside the myths of ancient legend. Showmen and peddlers of bogus medicine sneak along the passageways and slide into the vacant seats of philosophers and orators. Investigative journalists and rebel spies cower in the shadows. They are visibly terrified, as if haunted by Walter Benjamin’s comment that one of the defining features of fascism is ‘the aestheticisation of politics’.2 Surely this cannot be happening here? But it is, and in the Chamber of the House applause indicates that the garage mechanics are all agreed, there is no doubt that the engine works. The differences of opinion revolve around what colour to paint the bodywork and which type of lubricant should be used to ensure the engine ticks over with regularity and predictability. This is a profoundly depressing situation and we should neither believe nor accept it.

3

A detailed map of the city is laid out on the table. Hands sweep with a dramatic blur across the streets and squares. One of them picks up a fat pencil and begins to draw on the paper. The fingers compose two circles, one at a 500-metre radius from the Winter Palace the other at a 1,000 metres, and proceed to plot a series of smaller circles indicating the key places and intersections to be targeted in the coming insurrection. Strategic crossroads, the railway stations, the post and telegraph offices, bridges, key banking institutions and the Peter and Paul Fortress – the map of the city becomes a battle plan.3

Q3. But this is all politics, what about architecture?

There are exceptions, but historically architects have tended to work for those with power and wealth. It was in many ways the original bourgeois profession, so we should not be surprised that many a professional architect is happy to be employed as capitalism’s decorator, applying the finishing touches to an edifice with which they have no real quarrel. As for the would-be rebel, even the architect’s and builder’s cooperative fully armed with a radical agenda to change the world for the better is required to make compromises in order to keep a business afloat. All alternative practices working within the context of a capitalist society still have to make some sort of surplus or profit if they are to survive in the market place. This said, there are ethical and moral choices to be made. It would be comforting to think that the majority of contemporary architects’ firms would have refused to design autobahns, stadiums and banks with building materials mined by slave labourers in 1930s Germany. How is it, then, that seemingly intoxicated by the promise of largesse and oblivious to the human degradation and environmental catastrophe unravelling in the Gulf, architectural firms are clambering over bodies to collect their fees from reactionary authoritarian governments and corrupt dictators who deny civilian populations basic democratic rights?4 Why is it that so many firms, in order to satisfy a ‘werewolf hunger for profit’, are happy to ignore the labour camps holding building workers in virtual prison conditions? There is no polite way of describing what amounts to amnesiac whoredom. But on this and other related matters the architectural and building professions remain largely silent, an unsettling quiet that is paralleled in Britain by the absence of any socially progressive movement within the architectural community that questions and confronts the ideological basis of the neo-liberal project.

1.3 ‘Architects, don’t work for repressive regimes and dictators’. Third Reich Air Ministry, Berlin

4

Tearing up the theatrical rulebooks on the relationship between actors and audience, workers transform the steps of the Winter Palace into what looks like a set from an Expressionist film. A giant three-dimensional version of Lissitsky’s print, ‘Red wedge defeats the whites’, a collision of cubes, pyramids and a distorted house are constructed to camouflage the pastel blue stucco facade. This is the stage on which the revolutionaries re-enact the occupation of the Royal Palace and the arrest of Kerensky’s provisional government on a nightly basis with a cast of thousands. Something special had been unleashed. It makes perfect sense. ‘We workers will no longer listen to our bosses in the factory, so why should we listen to them in the art salons and galleries? Away with the grand masters, away with the worship of experts, art into life, art into the street, the streets are our palettes, our bodies and tools our implements.

Q4. But isn’t the Left dead and aren’t you trying to raise ghosts and spectres?

There is perhaps an element of necromantic wishful thinking. It is probably true that the Left in Europe, despite the anti-capitalist movement, has scattered, punch-drunk and still reeling from the ideological battering ram unleashed against it. Like whipped autumnal leaves spread across the fields after high winds, it waits for a rake to pile it into a recognisable and coherent shape. But new alliances form at the very moment when all seems lost. The reclamation of the lost, buried and hidden is the subject matter of archaeology. But we also need to conduct a careful archaeological dig to reclaim the oft forgotten historical attempts to forge an alternative to capitalism. Central to this project of rebuilding opposition is to rescue the word socialism from its association with the violent state capitalist dictatorships of the former Soviet bloc. With careful scrapes and incisive cuts our archaeological dig reveals a library full of eminently modern and prescient ideas like equality of opportunity, social justice, the redistribution of wealth, the social ownership of resources – concepts that are easy to brush off and reinvigorate. The excavations continue and we discover that anarchism, far from its infantile representation as an ideology of chaos and disruption, offers other extraordinary ideas that can be added to the library index. Infused by a resolute defence of individual liberty, it speaks of self-management, of independent action, of autonomy, and of opposition to all forms of social power, especially that wielded by the State.

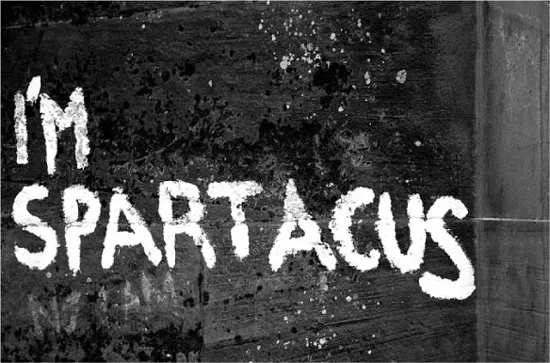

1.4 ‘Architect, are you?’ Graffiti, Glasgow

5

Comrades, take the time to read, digest and enjoy the declaration on land. Savour these words, ‘the landowner’s right to possession of the land is herewith abolished without compensation’.5Does that not sound magnificent? It is not poetry in the sense of Pushkin or Lermontov, but it possesses a timeless lyrical quality. We have achieved something that no other people in human history have managed. We have socialised the land on behalf of all of society’s members at the same moment as occupying all the key buildings of the state and capitalist class. It is an act that, if it were to all end tomorrow, would nevertheless resound through the ages like the tales of Homer and Odysseus.

Q5. But I’ve heard it all before, capitalism this, capitalism that, shouldn’t we just accept that the best we can do is to ameliorate the worst aspects of capitalist building production? I can see why one might become anti-capitalist, but shouldn’t we learn to accept that’s just the way the world is?

That is indeed how the world is. The question is, do we think it should be? Is the capitalist system really the best way of handling human affairs and organising how we make and use our buildings and cities? It is true that capitalism has proved to be remarkably resilient and even in moments of profound economic crisis, has managed to restructure economic life so that capital accumulation can recommence. Yet it remains dominated by the contradictions that arise from a social and economic system based on the private accumulation of capital and the economic exploitation of workers. It is a 300-year old history disfigured by slavery, colonial domination, socio-spatial inequality, and fascism – scars that are viewed as aberrations arising from some other planet, rather than what they are, structural features of capitalist economic domination. Despite this history of social and psychological violence, we are told that the organisation of a mythical free market in land and building services and the relentless commodification of all aspects of the built environment are the best ways of building our villages, towns and cities. Simultaneously, attempts to provide ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- 1 The Glimmer of Other Worlds: Questions on Alternative Architectural Practice

- 2 Violent Stone: The City of Dialectical Justice – Three Tales from Court

- 3 Paris: Ghosts and Visions of a Revolutionary City

- 4 Letters from the Front Line of the Building Industry: 1918–1938

- 5 Foreign Bodies: Corps Etranger

- 6 The (Dis)Integrating City: The Russian Architectural and Literary Avant-Garde

- 7 Sketches of War II: The Graveyards of Historical Memory

- 8 The Shadow of Economic History II: The Architecture of Boom, Slump and Crisis

- 9 Scares and Squares II: A Literary Journey into the Architectural Imaginary

- Bibliography

- Index