![]() PART 1

PART 1

Professional Theories![]()

1

Setting Standards for Public Library Environments

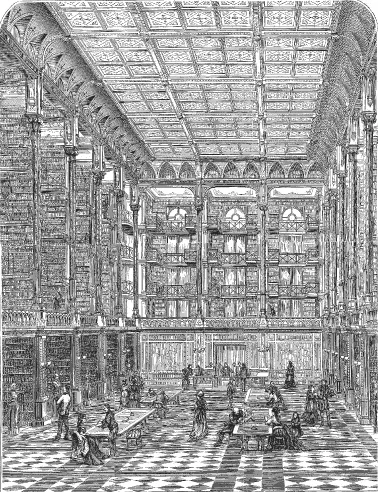

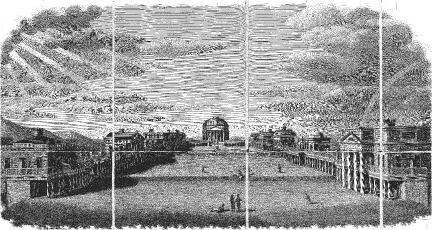

Figure 1.1 Engraving depicting men, women and children using the proposed Cincinnati Public Library. Source: Harper’s Weekly Supplement March 21st 1874

It is important to recognise the architectural frame of reference from which the theoretical aims of the public library were imagined and to identify the key authors who circumscribed those definitions on behalf of others. This chapter marks out the short time frame in which ideal plans challenging political principles for public accessibility were enabled by progress in technology to proliferate as environmental standards around the world. Key architectural precedents, both public and private differentiate the environmental design of public libraries as predominantly either top lit or side lit rooms. The direction of the light source raises a functional distinction in the character of public light; between light for being seen, and light to see with. From this, other contemporary building typologies can be used to explore experiments with the notion of transparency, in terms of civic navigation and customary behaviour in relation to light in public. Finally, the distinct professional preoccupations of architects and librarians and their lively discourse demonstrates their eagerness to establish design guidance with authority, a debate that led to demands for a “revolution” in library design in 1891.

The popular press proclaimed at the opening of Cincinnati public library in 1874: “no portion of the shelving is deprived of a proper amount of light” (Curtis 1874). Yet within two years, its librarian, W.F. Poole was to mount a prolonged and internationally publicised attack on architects precisely for its environmental failings. His criticism sparked a battle between the professions of librarians and architects over library design that raged for a further twenty years. Historians of library architecture, Van Slyck (1995: 1), Oehlerts (1991), Bobinski (1969), and Pepper (2006) all relate the fracas that emerged towards the end of the nineteenth century between American librarians and architects with regard to the design of libraries. The significance of the debate between user and designer here is to establish that the dispute was founded upon a librarian’s acute criticism of the environmental performance of his library’s design.

For both British and American architects, the idea of the early public library was a theoretical proposition, it called for revisions of previous assumptions of modes of social behaviour. Essentially, the concept of a public library was at odds with the entire weight of architectural precedent for the library typology, which had hitherto almost exclusively aimed to protect, conserve and limit access to literature within the confines of strictly defined monastic, scholastic, or simply privileged adult male groups. The progress of library design was to rapidly absorb the apparently conflicting requirements of security and access, of public surveillance and private navigation. As the number of libraries increased, so did the profession of librarianship, bringing with it a rapid, articulate and forceful, internationally co-ordinated client base that sought to direct the course of library design swiftly away from architectural assumptions of traditional precedents towards modern visions of economy and efficiency. This chapter seeks to re-frame the well documented conflict between architects and librarians more specifically as a reaction to the environmental consequences of theoretical projections by architects for a new typology which had assumed that environmental precedents of private spaces could be successfully adapted for public service.

Propagating Ideals

A global appetite for events that asserted a status quo internationally, such as World Exhibitions, grew during the nineteenth century. Oelherts (1991: 31) notes the impact upon Americans of the Paris Exposition of 1889. The Eiffel Tower, the nineteenth century plan of the city and its public spaces set a benchmark for the Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893 which attracted 25 million visitors over 6 months. The fair promoted the use of electricity and “focused the attention of all people on the changing American society from rural to urban life”. He emphasises the significance of the Exposition as a pivotal event for library design. Firstly for architects; Burnham and Root as well as McKim Mead and White were contracted to design the buildings, but also for librarians. W.F. Poole and Mervil Dewey who presented the American Library Association “model library” there. These endeavours were to succeed in distributing uniform equipment to public libraries in Britain and America throughout the twentieth century. This profitable achievement was the iteration of ideals developed over a lengthy discourse, not only between architects and librarians but also between nations.

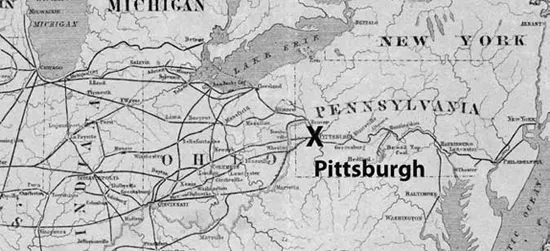

Map 1.1 Detail: Pennsylvania rail road and its connections. Office of the Pennsylvania railroad company Philadelphia, November 3rd, 1857. Source: Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division

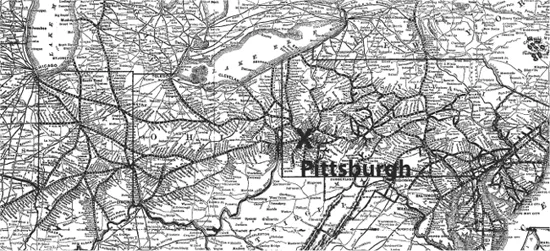

Map 1.2 General Map of the Pennsylvania Railroad and Its Connections Allen, Lane and Scott 1893. Source: Library of Congress Geography and Map Division

The transformative character of the period in question is dramatically shown by the difference between the two maps above, in which the expansion of the Pennsylvania Rail Road that critically connected the East Coast of America to the West is charted between 1857–1893. Not only was the steel rail connection between New York and Pittsburgh largely extruded from the Carnegie steel mills neighbouring the case study libraries of this book, but the contrast between the images encapsulates the pace of place-making in America that occurred just prior to the period under review.

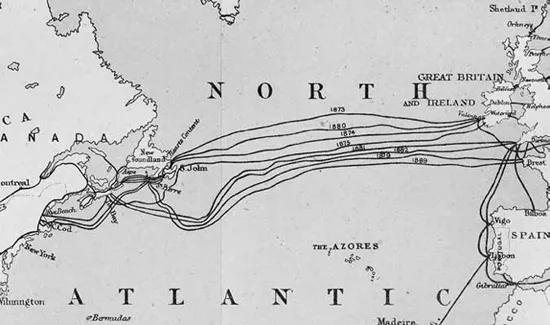

Simultaneously cables were laid connecting Europe and Africa, largely via Britain to America. The trans-Atlantic communicative links, in the form of the telegraph, were well established by the end of the nineteenth century. Preece’s map shows that between 1869 and 1882, eight cables had been laid across the sea-bed. The feasibility of communicating international standards was clearly enhanced by these new links.

The ideal of the public library challenged national identities and comparisons were made increasingly visible by progress in communication. The English library campaigner, Edward Edwards (1859: 165–6), described American library pioneers as men who “had before them the conversion of a vast wilderness into a civilized and religious community”. His description identifies the primal visionary significance of the library in the establishment of an independent American Republic. The contrast between British and American ideals and progress with respect to public library design was hugely influenced by their divergent political standpoints and was subsequently reinforced by technological advancement. The progress of global communication networks cannot be underestimated in viewing the migration of standards for public library designs. Not only the principles of Republican government but also the pace of settlement clearly put American ahead of British progress in the public library movement.

Map 1.3 Detail: “The Progess of Telegraphy: Map of submarine cables existing in 1883”. Source: Preece, ICE

Thomas Jefferson’s 1826 library and village design for the university of Virginia set a replica of the Pantheon at the heart of the campus and as Breisch described it: “symbolised Jefferson’s faith in the ability of public education to guide the new republic he had helped to foster” (1997: 57). The fundamental ambition of the public library in America not only predated but was also deliberately distinguished from the opaque power structures of British society, a symbol of clarity, democracy and republican ambition for legible government.

The functional aspects of the early public library were explicitly tied to symbolic conceptions of public space. Black, Pepper and Bagshaw’s (2009) thematic study asserts that libraries were conceived both as “Monuments” and as “Machines”. The origins of the dialogue lie in clear theoretical models of libraries designed by both architects and by librarians. Alternatives for the spatial arrangement of human knowledge had preoccupied eighteenth century European theorists who had imagined a freely accessible realm, which in itself represented a new, functional social permeability.

Figure 1.2 Detail: View of the University of Virginia 1827. Source: Special Collections, University of Virginia Library University of Virginia Libraries

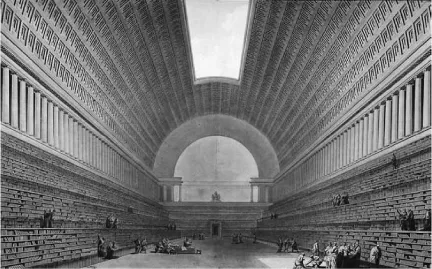

Figure 1.3 Vue intérieure de la nouvelle salle projetée pour l’agrandissement de la bibliothèque du Roi / Boullée invenit. Source: gallica.bnf.fr/Bibliothèque nationale de France

Boullée’s 1785 design proposal for the Bibliothèque Nationale presented pre-revolutionary Paris with a distilled ambition for a library design that was considerably more influential than might at first be assumed. His extrusion of the Pantheon dome to form a rectilinear top-lit agora would be realised in the form of steel-framed repositories populated by men, women and children across America within a century. However, the demand for public library design to respond to the needs of “service” and “efficiency” put librarians in diametric opposition to Boullée’s proposal:

It appeals effectively to those poetical sympathies which make us gaze delightedly on the Babylonian Palaces of Martin, and overlook, for the moment, their greater adaptability to cloud-land than to earth. (Edwards 1859: 714)

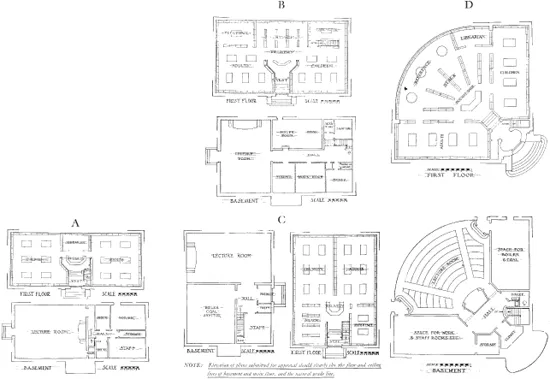

Figure 1.4 Leopoldo Della Santa: Della Costruzione e del Regolamento di una Pubblica Universale Biblioteca: con la pianta dimostrativa 1816

A librarian’s counter-proposal to the architect’s vision for an ideal building was first presented in the form of a diagrammatic plan produced by “a man of letters…(who) ...designs a library, at which architects would stand aghast, and in the arrangement of which the librarians have it all their own way” (Edwards 1859: 717). Leopoldo Della Santa’s plan, in contrast to Boullée’s projection, can be seen to epitomise early nineteenth century polemic with regard to the theory of library design. The theoretical schemes place the logistical interests of librarians in conflict with the vision of architects long before the ideas had been meted out in practice.

The proposed scheme for the new British museum library provoked debate on the principles of library design in Britain. An architect, Papworth (1853: 64), proposed an alternative ideal plan based upon environmental and operational principles: “no library, public or private, known to us, has been purposely built with a view to present economy and future expansion”. He proposed his own dodecahedron surrounding “the obeliscal chimney for heating and ventilation,” from which provision could be made for library expansion in segments in accordance with subject areas. He challenged readers to compare his plan with that proposed to Parliament for the British Museum Library by Panzizni and Smirke in the Return, No.557, ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 30th June, 1852.

Finally, a vision for library planning emerged that was related solely to visual supervision. It was critical to the development of the design of free access. In a section on “Libraries Projected”, Edwards supplied his own ideal lending library plan, promoting open access:

Figure 1.5 Plan and section of Proposed Expandable Library. Source: Papworth (1853)

Figure 1.6 Ideal plan for a small library building. Source: Edwards 1859

Edwards had reviewed the ideal panoptic plans of Delessert (1835: 11) which “facilitates both the service and the supervision of readers”. The policeman’s son had written to Jeremy Bentham and proposed an adaptation of his Panopticon ideal prison plan of 1785 as a model library plan. “On ne peut mettre en doute l’immense avantage pour la surveillance, d’être place au centre du bâtiment”. In 1799, Boullée (1799: 77) had also observed the benefit for library surveillance of providing radiating galleries “partent d’n centre commun”. However, its translator, Rosenau relates his idea to a literal translation of Pliny’s “prima in orbe”1 adding a greater theoretical legacy to the model.

As Black (2005) has noted, Foucault’s analysis of Bentham’s Panopticon was not applied directly to library design. However, it is interesting to note that in reality, a direct line of correspondence connects these ideas. The radiating diagram for the ideal supervision prevailed as a functional model for library design well into the twentieth century. James Bertram’s (1911a) guidance reiterated the idea that “Small libraries should be pland (sic) so that one librarian can oversee the entire library from a central position”. All eight Pittsburgh branch libraries built by Longfellow Alden and Harlow between 1898 and 1910 used the device.

By 1911, after Carnegie had funded the construction of 2094 libraries across Britain and America (Bostwick 1910: 211), his secretary, James Bertram (1911a: 2), neither architect nor librarian, announced that a memorandum, “Notes on Library Bilding (sic)” which “embodied the results of our own experience as well as suggestive criticisms of the authorities consulted” was to be sent with each subsequent promise of a library grant. It is evident that the principle of Bertram’s standards were generated in discourse and effected in practice long before the publication of his guidance, explaining Van Slyck’s (1995: 200) observation that his standards were already out of date by the time of their publication. Thus, whilst an equivalent document to the American library guidance was never published for use in British Carnegie libraries, many of the standards it espoused were already well known.

Figure 1.7 Bertram’s Plans from Notes on the Erection of Library Bildings 1911. Source: Carnegie Corporation New York Archive at Columbia University

Precedents for the Illumination of Free Access

A current library historian, Snape (2006: 41), describes the ambition for early public libraries as one of providing civilizing spaces for leisure in the industrialized towns of Northern England. Architectural precedents for such public spaces were sparse. Papworth (1853: 62), writing shortly after the passing of the libraries act, provided a brief list of the following exemplars of library buildings across Europe:

S. Mark, by Sansovino in Venice; the Laurentian by Michel Agnolo Buonarotti, at Florence; the Vatican at Rome; Brera at Milan; Bodleian, Radcliffe by Gibbs, and All Souls at Oxford; Nationale and Ste Geneviève at Paris; Ducal at Wolfenbuettel; Trinity College and University at Cambridge; Royal at Copenhagen; Imperial at St Petersburgh; Royal at Munich; and British Museum at London. The three great private libraries, considered as buildings, in England, may be those of Blenheim, Sion House, and Luton.

No...