![]()

1

A Study of Japanese Colonial Architecture in East Asia

Yasuhiko Nishizawa

PROLOGUE

Japan occupied Taiwan, Korea, and the northeast Chinese province of Manchuria from the late nineteenth century to the end of the Second World War. During this period, many Japanese architects, whom I titled “architects adventurers” in 1984, moved to these areas to design and construct buildings. This paper focuses on those buildings, which are examples of colonial architecture, and the Japanese architects who designed them in the first half of the twentieth century, as well as the relationship between these buildings and some of Japan’s colonial policies, including policies of both the Japanese government and the established colonial governments. In addition, I intend to demonstrate what Japanese colonial architecture was in the first half of the twentieth century by analyzing it from three viewpoints—uses and planning, structure and materials, and style and design—and to discuss the Japanese colonial architects who were active during that period.

I address the following four points: First, for the colonial governments and governors, each colonial building was a tool to display Japan’s ability to rule to the Great Powers and to the Asian people. Second, Japanese colonial architecture was the result of Japanese architectural education and Japanese architects’ studies from the nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century. Because of this, almost all Japanese colonial buildings—except government buildings in Manchukuo—adopted or modified a Western style. Third, no famous Japanese architects moved their bases to the Japanese colonies. Lastly, some of the Japanese colonial buildings dealt with the nature and climate of each colony.

This article is divided into three parts. The first part introduces colonial architecture and the typical buildings constructed by the Japanese colonial government. The second section analyzes some of the relationships between colonial architecture and colonial policies. The third section discusses the history of colonial architecture.

INTRODUCTION TO COLONIAL ARCHITECTURE

The first Japanese colonial government was the Taiwan Government-General, established in 1896. It was a successor of the former Taiwan Government-General, established in 1895 as a bureau of the Japanese Army, which had seized Taiwan from the Qing Dynasty and occupied it during the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895).

In the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), Japan occupied the Korean Peninsula and established the Tokanfu, the Residency-General that controlled the Korean emperor and the Korean government. In 1910, Japan made the whole of the Korean Peninsula a colony and established the Chosen Government-General, which was based on the Residency-General.

In China’s northeast province, Manchuria, Japan acquired two regions following the Russo-Japanese War: the south part of the Liaotung Peninsula, called Kanto-shu (Kwantung Province), which was leased territory from the Qing Dynasty, and the Railway Zone along the former Chinese Eastern Railway from Dairen (called Dalny by the Russians and now called Dalian) to Changchun. In 1906, Japan established two organizations to rule the two regions: the Kwantung Government at Ryojun (Port Arthur), which ruled Kwantung Province until the end of the Second World War, and the South Manchuria Railway Company (SMR) at Tokyo, which had administrative power over the Railway Zone. In 1907, the SMR shifted its head office from Tokyo to Dairen.

In 1931, the Kwantung Army, part of the Japanese Army, staged the Manchurian Incident. As a result of this, Manchukuo, a puppet government controlled by the Kwantung Army, was established in 1932 with its capital in Hsinking (Changchun). In 1937, the SMR Railway Zone was abolished, and administrative power was transferred to the Manchukuo government.

In 1937, the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) began, and the Japanese Army occupied many areas in China. The Japanese Army established a puppet regional government in each ruled Chinese territory except for Manchuria. From 1940 to 1945, the Japanese Army occupied all of Southeast Asia except for Thailand. After being defeated by the Allies in 1945, Japan lost all its colonies and ruled territories.

Using this historical outline, we can divide the Japanese colonies and ruled territories into two groups, and thus understand the Japanese architects’ building activities in each. The first group is comprised of Taiwan, Korea, and Manchuria—regions that were under Japanese rule for 40 to 50 years and that are acknowledged by almost all Japanese people as “former colonies.” The second group is made up of those regions in mainland China and Southeast Asia that were occupied by the Japanese Army for fewer than 10 years; almost all Japanese people know the history of these regions, but they are recognized as “occupied areas” only.

The Japanese architects’ building activities in the colonies and ruled territories can also be divided into two types. A lot of architects designed many new buildings in the colonies of Taiwan, Korea, and Manchuria, but in the occupied areas of mainland China and Southeast Asia, the main activities of the Japanese architects were the maintenance or improvement of the existing buildings. The following section discusses typical colonial architecture built in Taiwan, Korea, and Manchuria—the “former colonies”—only.

Government Office Buildings

When each Government-General was established in Taiwan and Chosen, existing buildings were converted into government headquarters and other government office buildings. The Kwantung Government and the SMR also began to use existing buildings.

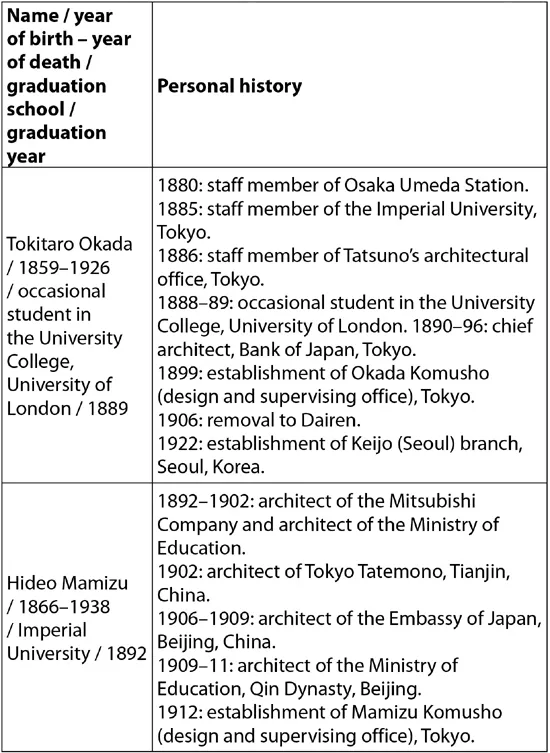

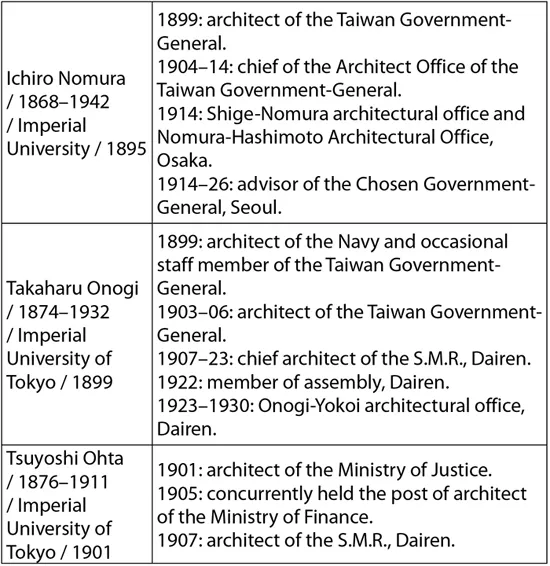

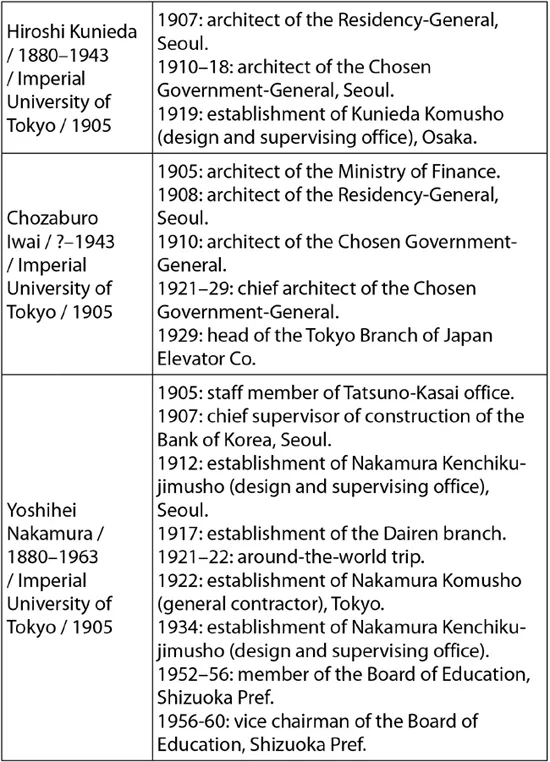

The Taiwan Government-General used the converted office building of the Taipei Regional Bureau, a one-story traditional Chinese townhouse called a siheyuan consisting of four houses surrounding a courtyard (Otsuji, Meiji-jidai no omoide 1). It was too small to work as a government-general office, so a competition to design a new building was held in 1907. No one won first prize; Uheiji Nagano (1867–1937), who graduated from the Imperial University in 1893 and would later become the chief architect of the Bank of Japan and one of Japan’s best architects of the twentieth century, won second prize. The Architect Office of the Taiwan Government-General designed a new office building based on Nagano’s proposal (see Figure 1.1). During the design process, the plan was changed in two major ways. First, the central tower was altered to make it 200 feet high. Second, a pediment was added to each corner. At that time, the chief of the Architect Office of the Taiwan Government-General was Ichiro Nomura (see Table 1.1), and under him one architect Matsunosuke Moriyama (1869–1949) who graduated from the Imperial University of Tokyo in 1897. Moriyama completed the final design of the building (Huang; Iwai). The new building was completed in 1919, 23 years after establishment of Taiwan Government-General. It was made of reinforced concrete covered with red bricks and built in the Queen Anne style with a high tower at its center and an encircling verandah (see Figure 1.2). Its shape was similar to a neo-Baroque-style building. There were no Japanese style or detail designs on the exterior or in the interior of the building. The plan of the outline was rectangular, and it featured a large central courtyard divided into two smaller courtyards. This plan was typical of Japanese government office buildings of that time, which were influenced by the neo-Baroque-style official and governmental buildings in Europe.

1.1 Nagano’s proposal for the design competition of the Headquarters Office Building of Taiwan Government-General in 1907

1.2 Exterior of the former Headquarters Office Building of Taiwan Government-General completed at Taopei in 1919

The Chosen Government-General appropriated the former office building of the Residency-General as its headquarters. However, the number of Residency-General workers was 93, only about 22 percent of the prescribed 430-person workforce of the Chosen Government-General. The building was too small, so the Chosen Government-General workers were divided among three office buildings in Seoul (Iwai). This was too inconvenient for them to work efficiently.

In 1912, the Chosen Government-General decided to build a new headquarters at Gyeong-bok-gung, a former palace of the Chosen Dynasty. The Chosen Government-General requested German architect George de Lalande (1872–1914), who had been in Japan since 1903, to design a new building (Hori). At the same time, one of the chief architects of the Chosen Government-General, Hiroshi Kunieda (see Table 1.1), was sent to the U.S.A. and Europe to view government office buildings there. When George de Lalande died suddenly in 1914, Ichiro Nomura, the chief architect of the Taiwan Government-General, was employed as a supervisor. Nomura and Kunieda collaborated on the design for the new building. In 1919, Kunieda retired from the Chosen Government-General. Before his retirement, he outlined the new building’s design for the Journal of the Architectural Institute of Japan and provided perspective (see Figure 1.3) and planning drawings (Kunieda).

However, the shape of the tower in Kunieda’s perspective drawing differed from that of the actual building (see Figure 1.4). In his drawing, the tower was a square plan, and the interior was exposed to the wind without glass in the windows.

1.3 Perspective drawing of the Headquarters Office Building of Chosen Government-General in the Journal of Architectural Institute of Japan, No. 381, published in January 1918

1.4 Headquarters Office Building of Chosen Government-General. Completed at Seoul in 1926

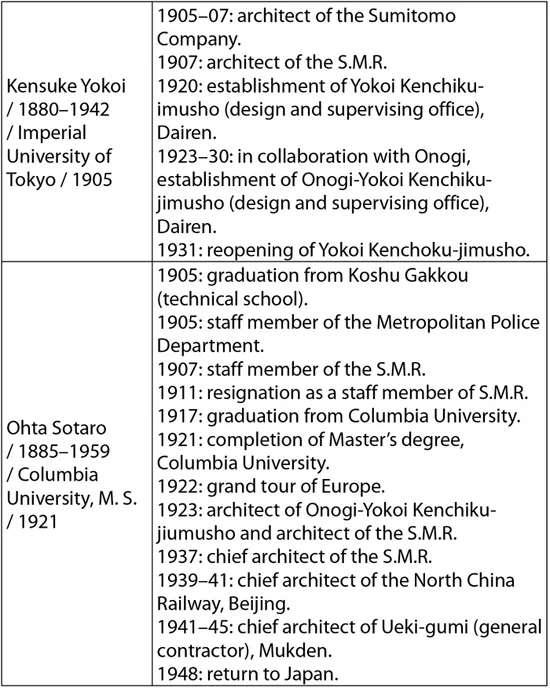

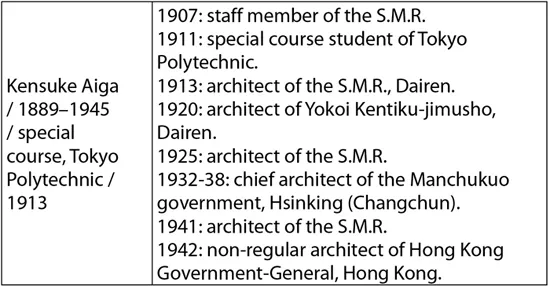

Table 1.1 Typical Japanese “Architects Adventurers” and their personal histories

It has not been possible to amend this table for suitable viewing on this device. Please see the following URL for a larger version http://www.ashgate.com/pdf/ebooks/9781472404367Tab1_2.pdf

After Kunieda retired, the Architect Office of the Chosen Government-General changed the design of the tower: the square plan was changed to a circular plan. The tower consisted of a cylinder covered with a baroque dome and topped with a lantern. The cylinder was supported by four posts and a coupled column was attached to each. The posts were needed to help the cylinder support the weight of the dome. The new building was completed in 1926, 16 years after establishment of Chosen Government-General. It was made from reinforced concrete covered with a granite exterior and designed in the neo-Baroque style, with a high tower and an encircling verandah. It was very similar to the headquarters of the Taiwan Government-General, which was completed in 1919.

There are two important points to note. First, neither government-general built new headquarters as soon as possible after its establishment. This indicated that it was more important for each government-general to construct public buildings rather than new headquarters. In Taiwan and Korea, for example, some hospitals and schools were built before the headquarters buildings. Second, both headquarters feature a symmetrical façade with a high tower, and both were based on the neo-Baroque style, which symbolized Japan’s occupation and rule of each colony. This indicated that both of the colonial governments would not adopt the Japanese traditional style for their headquarters, but this was not the case for the Manchukuo government following the Manchurian Incident.

In Manchuria, the Kwantung Government and the SMR had headquarters like those in Taiwan and Korea. The Manchukuo government in the 1930s was quite a different case.

When the Kwantung Government began work at Ryojun, Port-Arthur, in 1906, it used a former Russian hotel as its headquarters until 1937, when a new building, made of reinforced concrete, was completed at Dairen. The building had a simple, long, narrow, symmetrical plan (Kanto shu cho chosha).

When the SMR began to work at Dairen in 1907, it first used the former Dalny City Hall, built by the Chinese Eastern Railway Company, as its Dalny branch. In 1908, it repaired and moved into a former commercial high school building (see Figure 1.5). After that, the SMR was not able to construct a new headquarters until 1945.

1.5 Headquarters of the South Manchuria Railway Company

1.6 Manchukuo Government Office Building No. 1

Like Taiwan and Korea, the Kwantung Government and the SMR did not build new headquarters soon after they were established. Instead, they constructed public buildings, which were needed in order to maintain their rule and improve the standard of living in each colony.

The Manchukuo government, under the Kwantung Army, was different. In 1932, the Manchukuo government employed architect Kensuke Aiga (Aiga), who had been with the SMR since 1911 as the chief of their architect office (see Table 1.1). He designed two plans of new government office buildings with the same plan but different exteriors. The firs...