![]()

Chapter 1

New Downtowns: A New Form of Centrality and Urbanity in World Society

Ilse Helbrecht and Peter Dirksmeier

Two questions provided the occasion for this volume: which forms of urbanity can be identified for the cities of the 21st century? And can these new forms of urbanity be planned? With these questions, this volume aims straight at the heart of urban research. Urbanity is a classical term which has inspired the imagination and conceptual vitality of the field ever since the scholarly study of cities began, whether in urban sociology, geography, economy or ethnography. All the great thinkers on cities in the 20th century, whether Robert Park (1915), Walter Benjamin (1928/2001), Jane Jacobs (1961/1992), Lewis Mumford (1961) or Georg Simmel (1903), have asked themselves the question: what differentiates urban life from rural situations? And what exactly is urbanity?

The debate on urbanity reached an odd stasis at the end of the 20th century. While, on the one hand, no new theoretically inspired definition of urbanity was being discussed (Dirksmeier 2009), relatively innovative urban developments in local city building projects could be observed at the same time. New types of cities and neighbourhoods arose. However, they were not – or have not yet – been included in a new terminology of urbanity. That is the state of the question from which the present volume proceeds. We are looking for a new type of urbanity in the 21st century. To do this, we will use particular sectional developments in cities as a lens through which to conceptualise and exemplify the new urbanity.

Our thesis is thus that at the beginning of the 21st century, a new type of urbanity presented itself. And this new form of urbanity can, to some degree, be planned. Its contours can be especially clearly seen in a particular, very recent type of city centre, the new downtown. Thus, we’ll develop the idea of the new downtown in order to outline a few basic characteristics of the new urbanity of the 21st century. The phenomenon of the new downtown – such is our thesis – is a completely new category of urban area in the globalised world. It is distinguished by at least four characteristics. Firstly, it can be planned to some degree and thus owes its development in large part to deliberate planning and design. Secondly, it is defined by designs which aim to stand out from the traditional geographic imagination of the old downtown, whether in Europe, Asia or America. Thirdly, the new downtown intends to distinguish itself as a representative of a new performative urbanity, and to move existing forms of urbanity in the old downtown forward. And that brings us to the fourth decisive force behind the new urbanity of the new downtown. It is based on a new form of centralisation. This emerging centrality of the new downtown properly belongs to the global conditions of contemporary society. Contemporary society must be described more precisely than as just a world society. It is also the global character of economics, politics and lifestyles, which, with the new downtowns, creates a unique place in the cities for a new form of centrality. A world society opens up a new framework of reference for processes of centre formation which goes beyond the concepts of globalisation and the global city (Sassen 1991). From the perspective of the world society, a new centrality is not just about the control capacity of world markets through transformation of the centre, as Saskia Sassen has aptly established. The world society on the horizon also means a new centrality and urbanity, which can expand economically fixed perspectives and also proceed on the basis of communication of social systems across national borders, from the public realm to world literature to the lifestyle of global milieus.

In this volume, we and the other authors investigate this new quality of inner-urban development with regard to the conditions of a world society. In the following introduction, we attempt to outline a few basic features of this new development. What characterises the new downtown as a new type of urban space? How does it arise? How does it work? And what social consequences and conflicts are inherent to it? In the individual chapters that follow, specific aspects of this new development in city centres will be looked at in more depth.

Why New Downtowns?

The city centre is no longer necessarily in high demand. Instead, the value of the city centre as such can only be proved within a specific social structure. In the ages of feudalism and industrialisation, city centres were traditionally the place where land had the highest price and where the most buildings were constructed (Alonso 1983). This high demand and the social significance of the city that came with it both increased and decreased in recent years. In the wake of globalisation and the metropolisation of urban development, middle classes and elites rediscovered the desirability of proximity to the city centre (Butler and Robson 2003; Ley 1991, 1997; Williams and Smith 2007). This led to an urban renaissance which initially applied functionally and spatially only to the traditional city centres and the adjoining neighbourhoods. Since the 1960s, the mass phenomenon of gentrification (Glass 1964) and the return of the city centres (Helbrecht 1996; Lees et al. 2008; Ley 1980) has been under discussion, initially as a niche phenomenon, and then by the 1990s at the latest as the mainstream of urban development in both Europe and North America as well as Australia. On the other hand, the status and functionality of the centres have again changed remarkably in the wake of globalisation and the development of the world society. Through processes of disembedding (Giddens 1996: 33), globalisation leads to a loss in the significance of old centres due to decontextualisation.

The phenomenon of the new downtowns is situated precisely at the intersection of two movements: the increased significance of old centres due to gentrification with the formation of a new centralism, and a changed urbanity under the conditions of a globalised contemporary society or world society.

The current social relations can be most accurately described by a type of society which has evolved from the service society, but relinquishes the demand for a relational social unity and no longer has recourse to an – unrealistic – precondition of homogeneity and internal connectivity as essential constituents for a society. The term world society actually describes this type of society (Burton 1972; Heintz 1982; Luhmann 1975/1991; Stichweh 2000). Describing contemporary society as a world society does not negate the existence of nation states; it does, however, serve to emphasise that nation states are structurally identical in a variety of unexpected dimensions and that they are evolving along similar lines (Meyer et al. 1997: 145). State boundaries remain important but are no longer a determining factor: ‘State boundaries are significant, but they are just one type of boundary which affects the behaviour of world society’ (Burton 1972: 20). Particularly with regard to future developments in the 21st century as well as questions concerning a future urbanity, it is necessary to think about the perspective of the world society as a premise for the development of urban spaces and centres. The contemporary type of society is no longer organised as a differentiation between the centre and the periphery in the same way that it is not structured as an industrial or service society. Modern society can be considered much more strongly in terms of a world society and as the best system of organisation for all structures and processes of social systems currently existing at a global level (Stichweh 2000: 11–12). Without the globalisation of cultural codes, material products, financial services and political conflicts, it is no longer possible to understand local developments. The term globalisation on its own, however, is not enough to describe the quality of this type of society. It refers more to the situation within which expansion occurs or to the de-localisation of heretofore limited phenomenon without registering the new system of an all-encompassing quality which the phenomenon of globalisation uses for its own creation (Stichweh 2000: 14).

World society possesses this all-inclusive quality which serves as the most extensive system of inter-connecting communication. But this does not necessarily mean that a sort of ‘one world’ will now emerge. The hallmark of a world society is characterised more so by a lack of homogeneity. That is why a global framework of reference is relevant for nearly all differentiations, structural formations and processes, in spite of and particularly because of all noticeable peculiarities, all absence of synchronicity throughout historical development as well as all the spatial differences which appear in world society and which are caused by it (Bahrenberg and Kuhm 1999: 194). With the collapse of society into a single emerging system of communication, it is important to focus our attention on traditional urban society. Urban spaces still exist and they are growing. Nonetheless, there are no longer any spatial barriers between more or less autonomous, co-existing societal segments. Centrality no longer automatically derives from the social order. Hence, urban society cannot simply be distinguished from something in its environment. But world society continues to establish urban spaces in local–global communication processes at an intense level.

The two-pronged demand for a) social goods as well as b) the economic product ‘city centre’ has, in specific cities and specific situations, produced a run on the development of city centres and their surrounding neighbourhoods. For those cities which profit from the special conditions of the new centrality of a world society, and also, due to their location near the sea or on a lake or river, have the advantage of a large industrial district and old industrial waterfront districts near the city centre, there are special opportunities. Such cities carve out a niche for the new centrality of the globalised world society near their old downtown. Thus, large-scale urban projects try, through waterfront redevelopment for example, to produce local centrality for global dimensions. In such cases as New York Battery Park, the London Docklands, the Barcelona Strand, in Buenos Aires or the Hamburger HafenCity, local resources can be used to creatively meet the new demands placed on the city centre by means of expansion. Young areas arise in direct proximity to the old city centre: the new downtowns. They have a certain fascination for businesses, planners, residents and researchers due to their unique spatial and historical situation. Very near, sometimes just a stone’s throw from the old city centre, an extraordinary process takes place on the remains of the industrial society and in the former warehouse districts and ports: inner-city expansion is taking place in inner-city locations using existing spaces. This is urban development under growth conditions. The proximity to the old centre and the concomitant significant spread from it characterise the locational strategy of the new downtowns. This is a paradoxical gesture, as is, according to Lefebvre (2003), typical for urban processes.

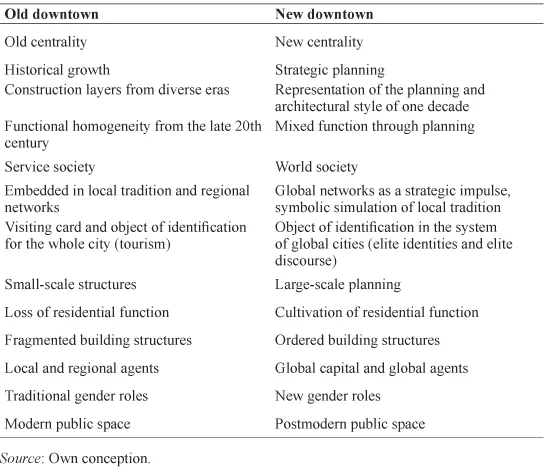

Table 1.1 Characteristics of the old and new downtown

The comparison on the basis of these descriptive differences shows that the category of the new downtown can only be understood in terms of its new social functions and global embedding.

In the Chicago School, especially for Ernest W. Burgess (1925/1967) the city centre was more than just the spatial centre of the city. Instead, the city centre had contained all functions and social classes of city’s population at an earlier point in the development of the city. It was the functional centre of the city. Only after the process of both centrifugal and centripetal expansion did the modern metropolis with its differentiated structures form. The city centre is thus, for the Chicago School, the cradle of urban development. It functions like an incubator: it is a dynamic centre and central motor for all the other processes. In the course of the 20th century, however, the old downtown in Europe, Australia and the United States and Canada initially lost significance and function for the city as a whole. The decline began with the loss of the residential function, which took on an increasingly one-sided usage structure and with that impoverishment due to the dominance of retail usage. Once retail had reconstituted itself in chain stores, the inner city seemed to have lost its special character. Even small businesses moved out to the suburbs. The decline of the old downtown thus seemed certain. Resistance on the part of many old downtowns to regain significance by building inner-city shopping centres to emulate the retailer’s suburban malls is, especially in Europe, a desperate attempt to copy a one-time suburban success in the old city centres. Most architects, geographers, urban sociologists and planners are aware that this is not an adequate way to transition the old city centre into a new epoch. The ‘malling’ of downtown would simply be a poor copy of the suburbs or surrounding towns instead of an original inner-city development (see Garreau 1991; Goss 1993; Popp 2004). The real significance of contemporary development of inner-city locations can be seen more precisely in the new downtowns. In this historical watershed, in which city centres have gone through a cycle of crowding, poverty and through the rediscovery of urban renaissance, it is an exciting question for urban research to compare the significance, formation and structure of the old and new downtowns.

What is decisive here is to understand the changes in function and significance in the centres which have occurred since the beginning of the 20th century. Even if many of the prerequisites for urban research according to the Chicago School no longer apply, one basic assumption remains an interesting point of departure for urban geographical research: how can city development be construed from the perspective of the centre? And what actually defines the centre of a city? Our suspicion for the 21st century is that urban spaces today must still, but not exclusively, be understood from the perspective of the centre because the urban principle itself is about forming centres and being central. The city centre can be an extraordinary place within the city which encourages discussion regarding its position and composition. It is not an uncontroversial place, because it is always a creative place, a ‘place for creation’ (Lefebvre 2003: 28). What makes urban places special in contrast to non-urban places is the collection of diversity.

What does the city create? Nothing. It centralizes creation. And yet it creates everything … The city creates a situation, the urban situation, where different things occur one after another and do not exist separately but according to their differences. (Lefebvre 2003: 117)

The core of the urban situation is thus the possibility of centrality by means of the connection and relation between diverse contents in one place. However, in the globalised contemporary society there is no longer a privileged place for the centre. Centrality itself has become mobile:

The essential aspect of the urban phenomenon is centrality, but a centrality that is understood in conjunction with the dialectical movement that creates or destroys it. The fact that any point can become central is the meaning of urban space-time. (Lefebvre 2003: 116)

The form of the city of the future will thus, especially in times of urban renewal in which the old downtown is restructured and re-invented, be derived from the form, content and shape of the new places of centrality. In this constant movement of centrality and the contradictory calls for a new centrality while the centre’s functions are being dissipated, the development of the new type of urban space, the new downtown, can be oriented. Before we go into the details of this new driving force and the structures of the new downtowns with the authors of this volume, the concept of the new downtown itself must be introduced. What is a new downtown? To what extent is it different from the old city centre? How is its urbanity articulated? And which features can be planned?

Copenhagen and Istanbul: Two New Downtowns as Visions of Urban Development

There are many examples of new centrality projects around the world, in which new downtowns have deliberately been made. As a point of departure for our theoretical considerations of the phenomenology, functionality and centrality of new downtowns, we would like to begin with two exemplary projects of the new urban renaissance. These projects should familiarise us conceptually as well as practically and visually with the phenomena of the new downtown. The examples are the developing area Örestad in Copenhagen and the Kartal Business District at the interface of Asia and Europe in Istanbul.

In Copenhagen, a revitalisation project which can be described as a new downtown extends over 210 hectares between the old city centre and the international airport. Under the supervision of the Örestad Development Corporation, urban expansion is taking place through four sub-projects and is pursuing the ambitious goal of placing Copenhagen on the international map of global cities. The project began in 1996, and actualisation is planned for 2017. Örestad is thus a new downtown which is in transition from both one defined urban structure to the next as well as from city and country. Spectacular architecture, including the work of British architect Sir Norman Foster (McNeill 2005), is interspersed with open public spaces and parks. The area is accessible by metro. Several universities have already moved into their new buildings, and a new concert hall with 1,800 seats has also been built here, while the broadcasting centre of the Danish Broadcasting Corporation (Evans 2009: 1027–8) is one of the largest media buildings in the world. With this development c...