eBook - ePub

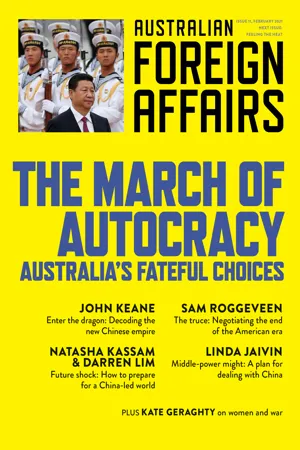

AFA11 The March of Autocracy

Australia's Fateful Choices: Australian Foreign Affairs 11

This is a test

- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

AFA11 The March of Autocracy

Australia's Fateful Choices: Australian Foreign Affairs 11

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

"China is an emergent empire of a kind never seen before... It's not a gunpowder or dreadnought battleship or B-52 bomber empire. It's an information empire, propelled by commercial interests." JOHN KEANE The eleventh issue of Australian Foreign Affairs examines the rise of authoritarian and illiberal leaders, whose growing assertiveness is reshaping the Western-led world order. The March of Autocracy explores the challenge for Australia as it enters a new era, in which China's sway increases and democracies compete with their rivals for global influence.

- John Keane probes Western misconceptions about China to show why its emerging empire might be more resilient than believed.

- Natasha Kassam & Darren Lim explore how Xi's China model is reshaping the global order.

- Sam Roggeveen considers Washington's stance on China and whether Biden can seek to restore US primacy.

- Linda Jaivin discusses how Australia might use its strengths as a middle power to combat China's influence.

- Huong Le Thu suggests how Australia can improve its South-East Asian ties.

- Kate Geraghty lays bare the horrific impact that war can have on women.

- Melissa Conley Tyler reveals the crippling impact of Australia's underfunding of diplomacy.

-

PLUS Correspondence on AFA10: Friends, Allies and Enemies from Charles Edel, Rikki Kersten and more.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access AFA11 The March of Autocracy by Jonathan Pearlman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Geopolitics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Reviews

Our Bodies, Their Battlefield: What War Does to Women

Christina Lamb

HarperCollins

HarperCollins

It is August 2018, and I am sitting with a reporter in a dark, hot room in the Kasaï region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It all feels like a tragic déjà vu. It has been almost ten years since I was last in the DRC. This time, we are on the other side of the country, in another conflict, covering the same issue – rape and sexual slavery is being used as a weapon of war.

A window in the room illuminates each woman as she tells her story. Some are pregnant or holding a baby. Defiant, brave, tired and far from the world’s attention, each of the women – Kabadi, Njiba, Marcelina, Elise, Vero, Bibisha, Monique, Monika, Tshilanda, Jose and Helene – walks us through the day she was raped and enslaved by armed men or boys, and how she eventually escaped or was released.

Kabadi Tshibuabua, who is from the Luba tribe, is nursing her baby daughter Philo on her knee – Philo was conceived in captivity. On a Sunday morning in April 2017, the Bana Mura militia came to Kabadi’s village. She tells us how they fled the killing, along with hundreds of other people from her village, Cinq. She grabbed her two children – Beya, her three-year-old son, and Ntumba, her five-year-old daughter. As they ran into the bush, the militiamen, including teenagers, chased them. Ntumba was too slow and was captured on the banks of the river, where the militia murdered her with machetes. Kabadi had no choice but to keep running, to try to save Beya. She made it to a nearby village, not realising it was already under Bana Mura control. On the day she arrived, she was raped by five men, the last a militiaman by the name of Mowaja Rasta.

For a harrowing hour, the villagers gathered to deliberate over whether to sacrifice Kabadi and Beya. Rasta argued against it, for he wanted her as a second wife. Kabadi became a sex slave in his house. She fell pregnant in the second month of her captivity. The village chief, on a whim, released her after three months.

A year later, she and her two children are staying in a church in Tshikapa, the provincial capital, where she is eking out a living. We are told they are three of the lucky sixty-four who were released or escaped. Another ninety-three women and children are still being held in captivity. We listen to Kabadi’s account. And then another woman enters the room, with a new account of horror.

It is brave women like this telling their stories whom you will meet in Our Bodies, Their Battlefield – a book that should be compulsory reading. In its pages, women who have endured the unimaginable speak out about what has happened to them and talk of their unwavering commitment for an acknowledgement of these war crimes and for a measure of justice.

One of the world’s leading foreign correspondents, Christina Lamb has reported on war for decades for The Sunday Times, exposing atrocities and the impact on civilians. She continues to do so with a dedication to telling people’s stories, and maintaining their dignity, that is not just inspiring but critical. Journalists like Lamb are doing vital work in documenting what happens in our world, in the hope that one day this preventable violence will stop.

Silence has often been history’s approach to women. In Our Bodies, Their Battlefield, Lamb takes us into the lives of those who have survived rape across four continents and seventy years of conflict, places in which no woman is exempt from the threat of sexual violence.

In 1943, Japanese soldiers came to Lola Narcisa’s village in the Philippines, forcing her into sexual slavery. She became one of the so-called “comfort women”. Now eighty-seven, she tells Lamb:

Until my last breath, I will shout to the whole world what they did to us. I still feel the pain. If only the Japanese government would just recognise and admit what they did to us. Whenever I hear on the news about women being raped, I get very angry.

Why are these things still happening to the Yazidis and others? Until we get justice, it will keep happening.

Why are these things still happening to the Yazidis and others? Until we get justice, it will keep happening.

And justice is rare. As Lamb points out, the ISIS members currently on trial at Nineveh in northern Iraq all face the same charge: terrorism, which in Iraq carries the death penalty. But despite the countless testimonies of survivors and witnesses, the first rape or abduction charge was not laid until March 2020, after Lamb’s book went to print. As Judge Jamal Dad Sinjari explains to Lamb when she asks why had no one been charged with keeping sex slaves or rape: “When these terrorists join ISIS, they are killing, raping, beheading, so it all counts as terrorism. That carries the death penalty, so there is no need to worry about the rape.”

Lamb reminds us, again and again, why the women she spent time with – and the many more like them – need justice. The Tutsi sisters – Victoire Mukambanda and Serafina Mukakinani, known as Witness JJ and Witness NN – gave evidence at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda trial in Arusha, Tanzania, that led to the world’s first conviction for rape as a war crime. Victoire explains to Lamb how family and friends tried to put her off, “but in the end I decided that for justice to take place someone had to say what had happened and tell the world, and I was prepared to do it so these people would be punished and this wouldn’t ever happen again”.

Those of us who cover war and its aftermath sometimes have the distinct feeling that we are recording testimonies not only of war, but of war crimes. In the absence of a functioning justice system, sometimes we are the only ones who will listen when people report what has happened to them. I agree with Lamb and those at the many NGOs at work in this area that more needs to be done to allow women, their families and those children born in captivity access to the legal system, physical and mental health care, and economic support to rebuild their lives.

In South Sudan in 2016, during the peace negotiations to end the civil war, I met a baby called Dakhoa, meaning “destruction of the world”. His mother, Chol, had fled the fighting and sought shelter at a United Nations camp for displaced peoples, where she still lives. During a lull in the conflict, Chol had gone home to retrieve her buried money, and on her way back to the camp was found by a group of government soldiers. “Some said, ‘We have to rape her.’ Some said, ‘No, what is rape? We have to kill her,’” she told us.

Three of the soldiers raped her, while the others fought over her money. Dakhoa, sitting in his mother’s lap, was conceived in this attack. Chol’s husband, a rebel fighter, was in the bush and didn’t know about the child. She still didn’t know if he would acknowledge what happened to her as a crime or accept Dakhoa. In the meantime, she said, “We just survive.”

A similar scene played out for us in Syria and northern Iraq under the brutal ISIS regime. During a visit to northern Iraq in 2019, several girls told us that they had witnessed mass killings and were forced into sexual slavery. Many were sold several times before being smuggled out or set free when the caliphate fell in March 2019. When battles are won or peace deals brokered, much attention is given to rebuilding – be it infrastructure or the economy – but the ordeal that women face continues. Their bodies may heal, but what has been taken from them cannot be restored. In many communities around the world, women who have been forced into sexual slavery and had children in captivity are shunned. An edict by the spiritual leader of the Yazidi declared that the Yazidi girls would be welcomed home, but the babies would not, for they had been fathered by ISIS. I know of two orphanages – one in Syria and one in Iraq – that care for these children. The children, like their mothers, will need support.

Lamb’s book raises many questions that, after reading, swirled in my head for days. But one kept returning: why aren’t war crimes against women talked about? My grandparents were German, and we grew up listening to the horrors of World War II, but I never heard them speak of these crimes. At school, we learnt of those killed in battles during both world wars – Gallipoli, Pearl Harbor, Normandy. We learn about the atrocities of genocide and ethnic cleansing, the Holocaust, prisoner-of-war camps such as Changi; we learn about politicians and generals, treaties and peace deals. Why not rape used as a weapon of war? I learnt about the comfort stations and women enslaved by the Japanese from a brief scene in the 1997 movie Paradise Road.

These war crimes must be included in history books. If we are mature enough to learn about mass killing and torture in high school, we should include the history of war crimes against women. It is a question of respect.

The outrage felt when reading Lamb’s book – about the crimes, and about the failure of meaningful convictions, and about the continued practices of rape and sexual slavery – is galvanising. Yet alongside the darkness of humankind, Lamb also introduces us to survivors, family members and activists whose determination for justice is inspiring. We meet “unexpected heroes” who put their lives in danger to help. One is Nobel Peace Prize laureate Denis Mukwege, also known as Doctor Miracle, a gynaecologist in the Democratic Republic of the Congo who has treated more rape victims than anyone on Earth. Despite several threats on his life, for decades he has treated survivors, including babies. We also learn about the incredible risks Abdullah Shrim, a beekeeper and trader, took to rescue 367 women and girls from ISIS. “And when ISIS came and killed and stole our women, I decided to do something,” he said. He persisted despite death threats: “My life is not more important than the tears of my niece or the other girls I have liberated.”

Lamb also probes why armed groups throughout history commit these crimes. We hear from those who work with survivors as they try to explain the motives behind the madness – to humiliate, as a form of ethnic cleansing, as punishment. It rings true to me.

In 2009, I was sitting with a reporter in another dark, hot room, this time in Goma, the capital of North Kivu province in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. There was one window, which illuminated a wooden chair. The account was not from one of the many women who have sat before us for hours and talked us through the worst days of their lives. It came from a former child soldier, Augustin. He estimated that in the six months he fought with a militia, he raped eighty women. As far as we know, he has never been charged for his crimes. He remains a free man.

“Our leaders would force us to rape, to humiliate them, our adversaries,” he said.

In almost a whisper, he describes how he raped so many women. “First I would rape alone, and then I would rape in a group. I looked at the older ones doing it, and I did it too … We would discuss it in a group, and we were proud to downgrade those girls. It was a matter of tribes, Mai Mai against Hutus … We used to come to the villages, burn the houses and rape the women of our adversaries. When I think about it now, I feel very, very bad.”

Augustin now holds talks with other men, aimed at discouraging rape. “I would like to ask forgiveness, but I don’t know how to reach all of them, so my way of asking forgiveness is talking about it.”

For many of the women survivors of this man-made plague, forgiveness is the last thing on their minds. Victoire – who Lamb describes pointing out the homes in the Rwandan village of Taba where Tutsi families were killed by Hutus – says of the banana tree groves on the hills, “I died so many times in those banana trees. I prayed to God to die.”

Zamunda, whom I met in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2009, and whose husband and children were killed moments before she was shot in the genitals by militia, simply told me, “I wish sometimes the soldiers had killed me. I don’t have anywhere to go, and no one to care for me.” The main reason women like Zamunda, and the Luba women in the Kasai region, were coming forward was to tell the world that there were still women and children being held in captivity by the Bana Mura militia.

We need more female reporters and photographers like Lamb to report not only on conflict but also its aftermath, and to allow the women to speak for themselves. This is not an easy book to read, but it is a vital record, part of the project to change how women are treated in conflict, achieve justice for those who have suffered and hold those who commit these war crimes to account. Women should never be residual victims of war. There can be no more excuses.

Kate Geraghty

In the Dragon’s Shadow: Southeast Asia in the Chinese century

Sebastian Strangio

Yale University Press

Yale University Press

In November 2012, Barack Obama was about to make history as the first sitting president to visit Cambodia, the country the United States had once secretly bombed as part of the Vietnam War. Shortly before his arrival, two large banners could be seen hanging outside the East Asia Summit venue in Phnom Penh. “Long Live the People’s Republic of China,” they proclaimed.

As far as diplomatic snubs go, this one was less than subtle.

The Obama administration was in the midst of its “pivot” to Asia to counter the rising power of China. Cambodia’s prime minister, Hun Sen, was making clear whose side he was on.

I covered the summit for the ABC and remember feeling relieved that there was actually a decent story, given the mind-numbing dullness of many regional forums.

A few months earlier, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) summit had imploded when Cambodia – that year, chair of the regional bloc – vetoed even a mild reference to China’s territorial grab in the South China Sea. For the first time in its history, the summit failed to issue a joint statement. In ASEAN terms, this was epic.

After all those years of “no strings attached” Chinese financing, the patient puppeteer had finally yanked. And Cambodia dutifully kicked.

Recounting the episode in his new book, Sebastian Strangio notes, “A few weeks earlier, Chinese President Hu Jintao had visited Phnom Penh, promising millions of dollars in investment and assistance.”

Strangio has a keen eye for moments like these – the nubs of history, where the money and power plays and symbolism are revealed, if only for an instant.

The Australian journalist spent eight years based in Cambodia (we both worked for The Phnom Penh Post, although at different times) and moved to Chiang Mai to finish writing In the Dragon’s Shadow.

Covering nine countries, it is a serious and rewarding account of China’s history, influence and possible future in South-East Asia, with little treasures scattered throughout, such as: “So far, ASEAN’s preferred approach has been to bind the Chinese Gulliver with a thousand multilateral threads … [of] the bloc’s signature mode of sometimes glacial consensus-based diplomacy. It is an approach that amounts to a sort of narcotization by summitry.”

Thinking back to the lows and highs of my ASEAN reporting experiences, desperately seeking anything even remotely newsworthy, that certainly resonates.

From the ritual kowtows before ancient emperors to the cash injections following the 1997 Asian financial crisis, Strangio does an admirable job of distilling centuries of history into a manageable primer. Two of the big themes of the book are the impacts of China’s showpiece Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and the role that South-East Asians of Chinese descent have played and might play in the future. “As in the US and Australia, where the CCP’s wooing of diaspora communities has been the subject of recent alarm, state efforts have extended beyond cultural outreach, seeking to convert Chinese cultural affinities into sympathy for [China’s] state policies and support for official schemes like the BRI,” he writes.

China’s actions sometimes undercut its efforts to woo, Strangio points out, leading to a diplomatic strategy that ends up “less charm and more offensive”.

Despite these quotable zingers, Strangio is most definitely not joining the chorus of critics taking pot shots at Beijing. I sense a writer genuinely trying to understand the motivations of China and each of its southern partners, and to fairly portray thei...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Copyright

- Editor’s Note

- John Keane: Enter the Dragon

- Natasha Kassam & Darren Lim: Future Shock

- Sam Roggeveen: The Truce

- Linda Jaivin: Middle-Power Might

- The Fix: Huong Le Thu on How Australia Can Supercharge Its Digital Engagement with South-East Asia

- Reviews

- Correspondence

- AFA Index compiled by Lachlan McIntosh

- The Back Page by Richard Cooke

- Back Cover