eBook - ePub

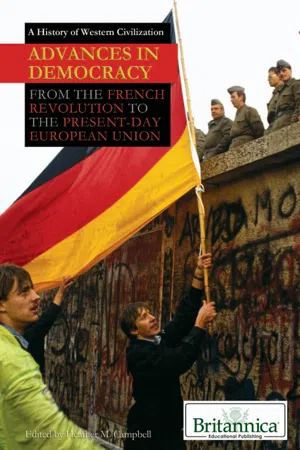

Advances in Democracy

From the French Revolution to the Present-Day European Union

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Advances in Democracy

From the French Revolution to the Present-Day European Union

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Beginning with the Industrial Revolution, Europe was seized by the spirit of political and social innovation and reform that has continued into the 21st century. The general atmosphere of the continent, reflected in the Romantic, Realist, and Modernist movements that swept through its nations, reflected a growing cognizance of previously neglected social realities that demanded action. This engaging volume chronicles Europe's transformations from the late 18th century through the present and examines the European response to both prosperity and war.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Advances in Democracy by Britannica Educational Publishing, Heather Campbell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1789–1849

Two types of revolution, economic and political, launched the modern era of European history. Beginning in England in the 18th century and continuing throughout Europe in the 19th, the traditional agrarian economy was transformed into one dominated by industry and machine manufacture. The Industrial Revolution, as this process became known, brought to Europe not only profound economic changes but also widespread social upheaval. Meanwhile, a popular social revolution that erupted in France in 1789 had overthrown, albeit temporarily, the French monarchy. The effects of the French Revolution, both political and cultural, reverberated through virtually the entire 19th century.

Some historians prefer to divide 19th-century European history into relatively small chunks. Thus, 1789–1815 is defined by the French Revolution and Napoleon; 1815–48 forms a period of reaction and adjustment; 1848–71 is dominated by a new round of revolution and the unifications of the German and Italian nations; and 1871–1914, an age of imperialism, is shaped by new kinds of political debate and the pressures that culminated in war. Overriding these important markers, however, a simpler division can also be useful. Europe dealt with the forces of political revolution and the first impact of the Industrial Revolution between 1789 and 1849. Then, between 1849 and 1914, a fuller industrial society emerged, including new forms of states and of diplomatic and military alignments.

THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

Undergirding the development of modern Europe between the 1780s and 1849 was an unprecedented economic transformation that embraced the first stages of the great Industrial Revolution and a still more general expansion of commercial activity. Articulate Europeans were initially more impressed by the screaming political news generated by the French Revolution and ensuing Napoleonic Wars, but in retrospect the economic upheaval, which related in any event to political and diplomatic trends, has proved more fundamental.

Economic Effects

Major economic change was spurred by western Europe’s tremendous population growth during the late 18th century, extending well into the 19th century itself. Between 1750 and 1800, the populations of major countries increased between 50 and 100 percent, chiefly as a result of the use of new food crops (such as the potato) and a temporary decline in epidemic disease. Population growth of this magnitude compelled change. Peasant and artisanal children found their paths to inheritance blocked by sheer numbers and thus had to seek new forms of paying labour. Families of businessmen and landlords also had to innovate to take care of unexpectedly large surviving broods. These pressures occurred in a society already attuned to market transactions, possessed of an active merchant class, and blessed with considerable capital and access to overseas markets as a result of existing dominance in world trade.

Heightened commercialization showed in a number of areas. Vigorous peasants increased their landholdings, often at the expense of their less fortunate neighbours, who swelled the growing ranks of the near-propertyless. These peasants, in turn, produced food for sale in growing urban markets. Domestic manufacturing soared, as hundreds of thousands of rural producers worked full- or part-time to make thread and cloth, nails and tools under the sponsorship of urban merchants. Craft work in the cities began to shift toward production for distant markets, which encouraged artisan-owners to treat their journeymen less as fellow workers and more as wage labourers. Europe’s social structure changed toward a basic division, both rural and urban, between owners and nonowners. Production expanded, leading by the end of the 18th century to a first wave of consumerism as rural wage earners began to purchase new kinds of commercially produced clothing, while urban middle-class families began to indulge in new tastes, such as uplifting books and educational toys for children.

In this context an outright industrial revolution took shape, led by Britain, which retained leadership in industrialization well past the middle of the 19th century. In 1840, British steam engines were generating 620,000 horsepower out of a European total of 860,000. Nevertheless, though delayed by the chaos of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars, many western European nations soon followed suit. Thus, by 1860 British steam-generated horsepower made up less than half the European total, with France, Germany, and Belgium gaining ground rapidly. Governments and private entrepreneurs worked hard to imitate British technologies after 1820, by which time an intense industrial revolution was taking shape in many parts of western Europe, particularly in coal-rich regions such as Belgium, northern France, and the Ruhr area of Germany. German pig iron production, a mere 40,000 tons in 1825, soared to 150,000 tons a decade later and reached 250,000 tons by the early 1850s. French coal and iron output doubled in the same span—huge changes in national capacities and the material bases of life.

Technological change soon spilled over from manufacturing into other areas. Increased production heightened demands on the transportation system to move raw materials and finished products. Massive road and canal building programs were one response, but steam engines also were directly applied as a result of inventions in Britain and the United States. Steam shipping plied major waterways soon after 1800 and by the 1840s spread to oceanic transport. Railroad systems, first developed to haul coal from mines, were developed for intercity transport during the 1820s; the first commercial line opened between Liverpool and Manchester in 1830. During the 1830s local rail networks fanned out in most western European countries, and national systems were planned in the following decade, to be completed by about 1870. In communication, the invention of the telegraph allowed faster exchange of news and commercial information than ever before.

New organization of business and labour was intimately linked to the new technologies. Workers in the industrialized sectors laboured in factories rather than in scattered shops or homes. Steam and water power required a concentration of labour close to the power source. Concentration of labour also allowed new discipline and specialization, which increased productivity.

The new machinery was expensive, and businessmen setting up even modest factories had to accumulate substantial capital through partnerships, loans from banks, or joint-stock ventures. While relatively small firms still predominated, and managerial bureaucracies were limited save in a few heavy industrial giants, a tendency toward expansion of the business unit was already noteworthy. Commerce was affected in similar ways, for new forms had to be devised to dispose of growing levels of production. Small shops replaced itinerant peddlers in villages and small towns. In Paris, the department store, introduced in the 1830s, ushered in an age of big business in the trading sector.

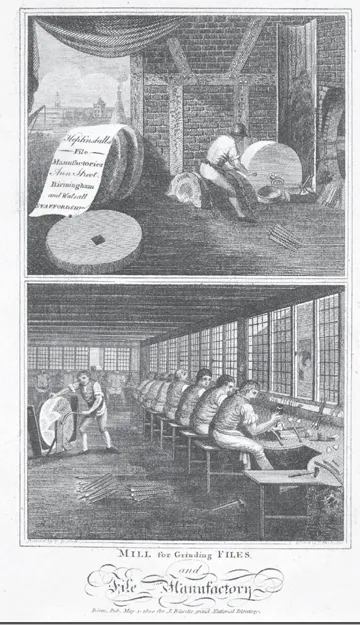

Rendering of workers at a British file factory. SSPL via Getty Images

Urbanization was a vital result of growing commercialization and new industrial technology. Factory centres such as Manchester grew from villages into cities of hundreds of thousands in a few short decades. The percentage of the total population located in cities expanded steadily, and big cities tended to displace more scattered centres in western Europe’s urban map. Rapid city growth produced new hardships, for housing stock and sanitary facilities could not keep pace, though innovation responded, if slowly. Gas lighting improved street conditions in the better neighbourhoods from the 1830s onward, and sanitary reformers pressed for underground sewage systems at about this time. For the better-off, rapid suburban growth allowed some escape from the worst urban miseries.

Rural life changed less dramatically. A full-scale technological revolution in the countryside occurred only after the 1850s. Nevertheless, factory-made tools spread widely even before this time, as scythes replaced sickles for harvesting, allowing a substantial improvement in productivity. Larger estates, particularly in commercially minded Britain, began to introduce newer equipment, such as seed drills for planting. Crop rotation, involving the use of nitrogen-fixing plants, displaced the age-old practice of leaving some land fallow, while better seeds and livestock and, from the 1830s, chemical fertilizers improved yields as well. Rising agricultural production and market specialization were central to the growth of cities and factories.

The speed of western Europe’s Industrial Revolution should not be exaggerated. By 1850 in Britain, by and large the leader still, only half the total population lived in cities, and there were as many urban craft producers as there were factory hands. Relatively traditional economic sectors, in other words, did not disappear and even expanded in response to new needs for housing construction or food production. Nevertheless, the new economic sectors grew most rapidly, and even other branches displayed important new features as part of the general process of commercialization.

Geographic disparities complicate the picture as well. Belgium and, from the 1840s, many of the German states were well launched on an industrial revolution that brought them steadily closer to British levels. France, poorer in coal, concentrated somewhat more on increasing production in craft sectors, converting furniture making, for example, from an artistic endeavour to standardized output in advance of outright factory forms. Scandinavia and the Netherlands joined the industrial parade seriously only after 1850.

Southern and eastern Europe, while importing a few model factories and setting up some local rail lines, generally operated in a different economic orbit. City growth and technological change were both modest until much later in the 19th century, save in pockets of northern Italy and northern Spain. In eastern areas, western Europe’s industrialization had its greatest impact in encouraging growing conversion to market agriculture, as Russia, Poland, and Hungary responded to grain import needs, particularly in the British Isles. As in eastern Prussia, the temptation was to impose new obligations on peasant serfs labouring on large estates, increasing the work requirements in order to meet export possibilities without fundamental technical change and without challenging the hold of the landlord class.

Social Upheaval

In western Europe, economic change produced massive social consequences during the first half of the 19th century. Basic aspects of daily life changed, and work was increasingly redefined. The intensity of change varied, of course—with factory workers affected most keenly, labourers on the land least—but some of the pressures were widespread.

For wage labourers, the autonomy of work declined; more people worked under the daily direction of others. Early textile and metallurgical factories set shop rules, which urged workers to be on time, to stay at their machines rather than wandering around, and to avoid idle singing or chatter (difficult in any event given the noise of the equipment). These rules were increasingly enforced by foremen, who mediated between owners and ordinary labourers. The pace of work accelerated. Machines set the pace, and workers were supposed to keep up: one French factory owner, who each week decorated the most productive machine (not its operators) with a garland of flowers, suggested where the priorities lay. Work, in other words, was to be fast, coordinated, and intense, without the admixture of distractions common in preindustrial labour. Some of these pressures spilled over to nonfactory settings as well, as craft directors tried to urge a higher productivity on journeymen artisans. Duration of work everywhere remained long, up to 14 hours a day, which was traditional but could be oppressive when work was more intense and walking time had to be added to reach the factories in the first place. Women and children were widely used for the less skilled operations. This was no novelty, but it was newly troubling now that work was located outside the home and was often more dangerous, given the hazards of unprotected machinery.

The nature of work shifted in the propertied classes as well. Middle-class people, not only factory owners but also merchants and professionals, began to trumpet a new work ethic. According to this ethic, work was the basic human good. He who worked was meritorious and should prosper, he who suffered did so because he did not work. Idleness and frivolity were officially frowned upon. Middle-class stories, for children and adults alike, were filled with uplifting tales of poor people who, by dint of assiduous work, managed to better themselves. In Britain, Samuel Smiles authored this kind of mobility literature, which was widely popular between the 1830s and 1860s. Between 1780 and 1840, Prussian school reading shifted increasingly toward praise of hard work as a means of social improvement, with corresponding scorn for laziness.

Shifts in work context had important implications for leisure. Businessmen who internalized the new work ethic felt literally uncomfortable when not on the job. Overall, the European middle class strove to redefine leisure tastes toward personal improvement and family cohesion; recreation that did not conduce to these ends was dubious. Family reading was a common pastime. Daughters were encouraged to learn piano playing, for music could draw the family together and demonstrate the refinement of its women. Through piano teaching, in turn, a new class of professional musicians began to emerge in the large cities. Middle-class people, newly wealthy, were willing to join in sponsorship of certain cultural events outside the home, such as symphony concerts. Book buying and newspaper reading also were supported, with a tendency to favour serious newspapers that focused on political and economic issues and books that had a certain classic status. Middle-class people also attended informative public lectures and night courses that might develop new work skills in such areas as applied science or management.

Middle-class pressures by no means totally reshaped popular urban leisure habits. Workers had limited time and means for play, but many absented themselves from the factories when they could afford to (often preferring free time over higher earnings, to the despair of their managers). The sheer intensity of work constrained leisure nevertheless. Furthermore, city administrations tried to limit other traditional popular amusements, ranging from gambling to animal contests (bear-baiting, cockfighting) to popular festivals. Leisure of this sort was viewed as unproductive, crude, and—insofar as it massed urban crowds—dangerous to political order. Urban police forces, created during the 1820s in cities like London to provide more professional control over crime and public behaviour, spent much of their time combating popular leisure impulses during the middle decades of the 19th century. Popular habits did not fully accommodate middle-class standards. Drinking, though disapproved of by middle-class critics, was an important recreational outlet, bringing men together in a semblance of community structure. Bars sprouted throughout working-class sections of town. On the whole, however, the early decades of the Industrial Revolution saw a massive decline of popular leisure traditions. Even in the countryside, festivals were diluted by importing paid entertainers from the cities. Leisure did not disappear, but it was increasingly reshaped toward respectable family pastimes or spectatorship at inexpensive concerts or circuses, where large numbers of people paid professional entertainers to take their minds away from the everyday routine.

The growth of cities and industry had a vital impact on family life. The family declined as a production unit as work moved away from home settings. This was true not only for workers but also for middle-class people. Many businessmen setting up a new store or factory in the 1820s initially assumed that their wives would assist them, in the time-honoured fashion in which all family members were expected to pitch in. After the first generation, however, this impulse faded, in part because fashionable homes were located at some distance from commercial sections and needed separate attention. In general, most urban groups tended to respond to the separation of home and work by redefining gender roles, so that married men became the family breadwinners (aided, in the working class, by older children) and women were the domestic specialists.

In the typical working-class family, women were expected to work from their early teens through marriage a decade or so later. The majority of women workers in the cities went into domestic service in middle-class households, but an important minority laboured in factories; another minority became prostitutes. Some women continued working outside the home after marriage, but most pulled back to tasks, such as laundering, that could be done domestically. Their other activities concentrated on shopping for the family (an arduous task on limited budgets), caring for children, and maintaining contacts with other relatives who might support the family socially and provide aid during economic hardships.

Few middle-class women worked in paid employment at any point in their lives. Managing a middle-class household was complex, even with a servant present. Standards of child rearing urged increased maternal attention, and women were also supposed to provide a graceful and comfortable tone for family life. Middle-class ideals held the family to be a sacred place and women its chief agents because of their innate morality and domestic devotion. Men owed the family good manners and the provision of economic security, but their daily interactions became increasingly peripheral. Many middle-class families also began, in the early 19th century, to limit their birth rate, mainly through increasing sexual abstinence. Having too many children could complicate the family’s economic well-being and prevent the necessary attention and support for the children who were desired. The middle class thus pioneered a new definition of family size that would ultimately become more widespread in European society.

New family arrangements, both for workers and for middle-class people, suggested new courtship patterns. As wage earners having no access to property, urban workers were increasingly able to form liaisons early in life without waiting for inheritance and without close supervision by a watchful community. Sexual activity began earlier in life than had been standard before the 1780s. Marriage did not necessarily follow, for many workers moved from job to job and some unquestionably exploited female partners who were eager for more durable arrangements. Rates of illegitimate births began to rise rapidly throughout western Europe from about 1780 (from 2 to 4 up to 10 percent of total births) among young rural as well as urban workers. Sexual pleasure, or its quest, became more important for young adults. Similar symptoms developed among some middle-class men, who exploited female servants or the growing numbers of brothels that dotted the large cities (and that often did exceptional business during school holidays). Respectable young middle-class women held back from these trends. They were, however, increasingly drawn to beliefs in a romantic marriage, which became part of the new family ideal. Marriage age for middle-class women also dropped, creating an age disparity between men and women in the families of this class. Economic criteria for family formation remained important in many social sectors, but young people enjoyed more freedom in courtship, and other factors, sexual or emotional or both, gained increasing legitimacy.

Changes in family life, root...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Age of Revolution, 1789–1849

- Chapter 2: The Early 19th Century: Romanticism and Other Cultural Developments

- Chapter 3: The Mid-19th Century: Realism and Realpolitik

- Chapter 4: A Maturing Industrial Society, 1849–1914

- Chapter 5: Modern Culture at the Turn of the 20th Century

- Chapter 6: Society and Culture Amid the World Wars, 1914–45

- Chapter 7: Postwar Europe, 1945 to the Present

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index