eBook - ePub

Africa to America

From the Middle Passage Through the 1930s

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Africa to America

From the Middle Passage Through the 1930s

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

At the expense of basic human rights, dignity, and decency, Africans were torn from their native countries and first brought to the United State as slaves. Yet even in the face of injustice and hardship they have endured since then, African Americans have been bolstered by the sacrifices, leadership, and determination of courageous individuals. This inspiring volume chronicles the history of African Americans—the triumphs and tragedies—from origins on the African continent to the end of the Harlem Renaissance.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Africa to America by Britannica Educational Publishing, Jeff Wallenfeldt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

OVERVIEW: FROM AFRICAN ROOTS TO WORLD WAR II

This overview of the first phase of African American history starts with a high-angle survey of a centuries-long period spanning the arrival of the first Africans in North America up to the onset of World War II. Its primary purpose is to introduce the people, events, organizations, and concepts that will be the focus of more detailed treatment in ensuing chapters, but it is also intended as a summary that provides sufficient background to allow readers to jump into the rest of the book at any point.

THE EARLY HISTORY OF BLACKS IN THE AMERICAS

Africans assisted the Spanish and the Portuguese during their early exploration of the Americas. In the 16th century some black explorers settled in the Mississippi valley and in the areas that became South Carolina and New Mexico. The most celebrated black explorer of the Americas was Estéban, who traveled through the Southwest in the 1530s.

The uninterrupted history of blacks in the United States began in 1619, when 20 Africans were landed in the English colony of Virginia. These individuals were not slaves but indentured servants—persons bound to an employer for a limited number of years—as were many of the settlers of European descent (whites). By the 1660s large numbers of Africans were being brought to the English colonies. In 1790 blacks numbered almost 760,000 and made up nearly one-fifth of the population of the United States.

Attempts to hold black servants beyond the normal term of indenture culminated in the legal establishment of black chattel slavery in Virginia in 1661 and in all the English colonies by 1750. Easily distinguished by their skin colour from the rest of the populace—the result of evolutionary pressures favouring the presence in the skin of a dark pigment called melanin in populations in equatorial climates—black people became highly visible targets for enslavement. Moreover, the development of the belief that they were an “inferior” race with a “heathen” culture made it easier for whites to rationalize black slavery. Enslaved blacks were put to work clearing and cultivating the farmlands of the New World.

Of an estimated 10 million Africans brought to the Americas by the slave trade, about 430,000 came to the territory of what is now the United States. The overwhelming majority were taken from the area of western Africa stretching from present-day Senegal to Angola, where political and social organization as well as art, music, and dance were highly advanced. On or near the African coast had emerged the major kingdoms of Oyo, Ashanti, Benin, Dahomey, and Kongo. In the Sudanese interior had arisen the empires of Ghana, Mali, and Songhai; the Hausa states; and the states of Kanem-Bornu. Such African cities as Djenné and Timbuktu, both now in Mali, were at one time major commercial and educational centres.

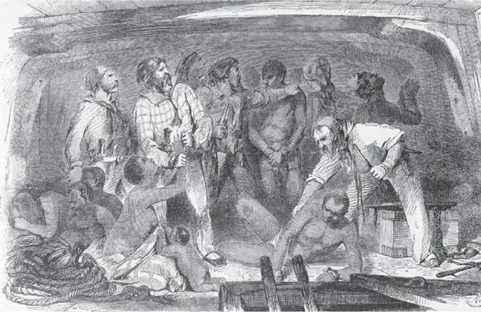

With the increasing profitability of slavery and the slave trade, some Africans themselves sold captives to the European traders. The captured Africans were generally marched in chains to the coast and crowded into the holds of slave ships for the dreaded Middle Passage across the Atlantic Ocean, usually to the West Indies. Shock, disease, and suicide were responsible for the deaths of at least one-sixth during the crossing. In the West Indies the survivors were “seasoned”—taught the rudiments of English and drilled in the routines and discipline of plantation life.

SLAVERY IN THE UNITED STATES

Black slaves played a major, though unwilling and generally unrewarded, role in laying the economic foundations of the United States—especially in the South. Blacks also played a leading role in the development of Southern speech, folklore, music, dancing, and food, blending the cultural traits of their African homelands with those of Europe. During the 17th and 18th centuries, African and African American (those born in the New World) slaves worked mainly on the tobacco, rice, and indigo plantations of the Southern seaboard. Eventually slavery became rooted in the South’s huge cotton and sugar plantations. Although Northern businessmen made great fortunes from the slave trade and from investments in Southern plantations, slavery was never widespread in the North.

Crispus Attucks, a former slave killed in the Boston Massacre of 1770, was the first martyr to the cause of American independence from Great Britain. During the American Revolution, some 5,000 black soldiers and sailors fought on the American side. After the Revolution, some slaves—particularly former soldiers—were freed, and the Northern states abolished slavery. But with the ratification of the Constitution of the United States, in 1788, slavery became more firmly entrenched than ever in the South. The Constitution counted a slave as three-fifths of a person for purposes of taxation and representation in Congress (thus increasing the number of representatives from slave states), prohibited Congress from abolishing the African slave trade before 1808, and provided for the return of fugitive slaves to their owners.

In 1807 Pres. Thomas Jefferson signed legislation that officially ended the African slave trade beginning in January 1808. However, this act did not presage the end of slavery. Rather, it spurred the growth of the domestic slave trade in the United States, especially as a source of labour for the new cotton lands in the Southern interior. Increasingly, the supply of slaves came to be supplemented by the practice of “slave breeding,” in which women slaves were persuaded to conceive as early as age 13 and to give birth as often as possible.

Scene aboard a slave ship, engraving by H. Howe, 1855. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Laws known as the slave codes regulated the slave system to promote absolute control by the master and complete submission by the slave. Under these laws the slave was chattel—a piece of property and a source of labour that could be bought and sold like an animal. The slave was allowed no stable family life and little privacy. Slaves were prohibited by law from learning to read or write. The meek slave received tokens of favour from the master, and the rebellious slave provoked brutal punishment. A social hierarchy among the plantation slaves also helped keep them divided. At the top were the house slaves; next in rank were the skilled artisans; at the bottom were the vast majority of field hands, who bore the brunt of the harsh plantation life.

With this tight control there were few successful slave revolts. Slave plots were invariably betrayed. The revolt led by Cato in Stono, S.C., in 1739 took the lives of 30 whites. A slave revolt in New York City in 1741 caused heavy property damage. Some slave revolts, such as those of Gabriel Prosser (Richmond, Va., in 1800) and Denmark Vesey (Charleston, S.C., in 1822), were elaborately planned. The slave revolt that was perhaps most frightening to slave owners was the one led by Nat Turner (Southampton, Va., in 1831). Before Turner and his co-conspirators were captured, they had killed about 60 whites.

Individual resistance by slaves took such forms as mothers killing their newborn children to save them from slavery, the poisoning of slave owners, the destruction of machinery and crops, arson, malingering, and running away. Thousands of runaway slaves were led to freedom in the North and in Canada by black and white abolitionists who organized a network of secret routes and hiding places that came to be known as the Underground Railroad. One of the greatest heroes of the Underground Railroad was Harriet Tubman, a former slave who on numerous trips to the South helped hundreds of slaves escape to freedom.

FREE AFRICAN AMERICANS AND ABOLITIONISM

During the period of slavery, free blacks made up about one-tenth of the entire African American population. In 1860 there were almost 500,000 free African Americans—half in the South and half in the North. The free black population originated with former indentured servants and their descendants. It was augmented by free black immigrants from the West Indies and blacks who had been freed by individual slave owners.

But free blacks were only technically free. In the South, where they posed a threat to the institution of slavery, they suffered both in law and by custom many of the restrictions imposed on slaves. In the North, free blacks were discriminated against in such rights as voting, property ownership, and freedom of movement, though they had some access to education and could organize. Free blacks also faced the danger of being kidnapped and enslaved.

The earliest African American leaders emerged among the free blacks of the North, particularly those of Philadelphia, Boston, and New York City. Free African Americans in the North established their own institutions—churches, schools, and mutual aid societies. One of the first of these organizations was the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church, formed in 1816 and led by Bishop Richard Allen of Philadelphia. Among other noted free African Americans was the astronomer and mathematician Benjamin Banneker.

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Overview: From African Roots to World War II

- Chapter 2: African Roots: Cultures and Kingdoms

- Chapter 3: African Roots: Art

- Chapter 4: Race and Racism

- Chapter 5: Slavery, Abolitionism, and Reconstruction

- Chapter 6: Law and Society

- Chapter 7: Religion

- Chapter 8: Education

- Chapter 9: Literature and the Arts

- Epilogue

- Timeline: 2nd Century CE to 1941

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index