eBook - ePub

American Literature from the 1850s to 1945

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

American Literature from the 1850s to 1945

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Deviating from the romanticism of earlier works, American literature that emerged after the mid-19th century adopted a distinct realism and an often critical view of American society. With penetrating analyses, writers such as Henry Adams and Upton Sinclair exposed fundamental flaws in government and industry, while Mark Twain and H.L. Mencken incisively satirized social ills such as prejudice and intolerance. Readers will encounter these and other great minds whose fluid pens challenged the status quo.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access American Literature from the 1850s to 1945 by Britannica Educational Publishing, Adam Augustyn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & North American Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

FROM THE CIVIL WAR TO 1914

As with the Revolution and the election of Andrew Jackson before, the Civil War was a turning point in U.S. history and the beginning of new ways of living. Industry became increasingly important, factories rose and cities grew, and agrarian preeminence declined. The frontier, which before had always been an important factor in the economic scheme, moved steadily westward and, toward the end of the 19th century, vanished. The rise of modern America was accompanied, naturally, by important mutations in literature.

LITERARY COMEDIANS

As the country was thrust into the chaos of the Civil War, some authors dealt with the wartime horrors by turning to humour as an antidote. Although they continued to employ some devices of the older American humorists, the group of comic writers that rose to prominence at this time was different in important ways from the older group. Charles Farrar Browne, David Ross Locke, Charles Henry Smith, Henry Wheeler Shaw, and Edgar Wilson Nye wrote, respectively, as Artemus Ward, Petroleum V. (for Vesuvius) Nasby, Bill Arp, Josh Billings, and Bill Nye. Appealing to a national audience, these authors forsook the sectional characterizations of earlier humorists and assumed the roles of less individualized literary comedians. The nature of the humour thus shifted from character portrayal to verbal devices such as poor grammar, bad spelling, and slang, incongruously combined with Latinate words and learned allusions. Most that they wrote wore badly, but thousands of Americans in their time and some in later times found these authors vastly amusing, and they helped to pave the way for the more consequential comic writers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

LOCAL COLOURISTS

The first group of fiction writers to become popular at this time—the local colourists—took over, to some extent, the task of portraying sectional groups that had been abandoned by writers of the new humour. Bret Harte, first of these writers to achieve wide success, admitted an indebtedness to prewar sectional humorists, as did some others; all showed resemblances to the earlier group. Within a brief period, books by pioneers in the movement appeared: Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Oldtown Folks (1869) and Sam Lawson’s Oldtown Fireside Stories (1871), delightful vignettes of New England; Harte’s Luck of Roaring Camp, and Other Sketches (1870), humorous and sentimental tales of California mining camp life; and Edward Eggleston’s Hoosier Schoolmaster (1871), a novel of the early days of the settlement of Indiana. Short stories (and a relatively small number of novels) in patterns set by these three continued to appear into the 20th century.

In time, practically every corner of the country had been portrayed in local-colour fiction. Additional writings were depictions of Louisiana Creoles by George W. Cable, New Orleans culture by Kate Chopin, Virginia blacks by Thomas Nelson Page, Georgia blacks by Joel Chandler Harris, Tennessee mountaineers by Mary Noailles Murfree (Charles Egbert Craddock), tight-lipped folk of New England by Sarah Orne Jewett and Mary E. Wilkins Freeman, New York City life by Henry Cuyler Bunner and William Sydney Porter (“O. Henry”), and life on the Mississippi River by the most prominent local colourist of them all, Mark Twain. The avowed aim of some of these writers was to portray realistically the lives of various sections and thus to promote understanding in a united nation. The stories as a rule were only partially realistic, however, since the authors tended nostalgically to revisit the past instead of portraying their own time, winnow out less glamorous aspects of life, or develop their stories with sentiment or humour. Touched by romance though they were, these fictional works were transitional to realism, for they portrayed common folk sympathetically, and concerned themselves with dialect and mores. Some, at least, avoided older sentimental or romantic formulas.

KATE CHOPIN

(b. Feb. 8, 1851, St. Louis, Mo., U.S.—d. Aug. 22, 1904, St. Louis)

Kate Chopin was an American novelist and short-story writer known as an interpreter of New Orleans culture. Chopin’s work has been categorized within the local colour genre. There was a revival of interest in Chopin in the late 20th century because her concerns about the freedom of women foreshadowed later feminist literary themes.

Born to a prominent St. Louis family, Katherine O’Flaherty read widely as a girl. In June 1870 she married Oscar Chopin, with whom she lived in his native New Orleans, La., and later on a plantation near Cloutiersville, La., until his death in 1882. After he died she began to write about the Creole and Cajun people she had observed in the South. Her first novel, At Fault (1890), was undistinguished, but she was later acclaimed for her finely crafted short stories, of which she wrote more than 100. Two of these stories, “Désirée’s Baby” and “Madame Celestin’s Divorce,” continue to be widely anthologized.

In 1899 Chopin published The Awakening, a realistic novel about the sexual and artistic awakening of a young wife and mother who abandons her family and eventually commits suicide. This work was roundly condemned in its time because of its sexual frankness and its portrayal of an interracial marriage and went out of print for more than 50 years. When it was rediscovered in the 1950s, critics marveled at the beauty of its writing and its modern sensibility.

Chopin’s stories were collected in Bayou Folk (1894) and A Night in Acadie (1897). The Complete Works of Kate Chopin, edited by Per Seyersted, appeared in 1969.

WILLIAM SYDNEY PORTER

(b. Sept. 11, 1862, Greensboro, N.C., U.S.—d. June 5, 1910, New York, N.Y.)

The American short-story writer William Sydney Porter, writing under the pseudonym O. Henry, was notable for his tales that romanticized the commonplace, in particular the life of ordinary people in New York City. His stories expressed the effect of coincidence on character through humour, grim or ironic, and often had surprise endings, a device that became identified with his name and cost him critical favour when its vogue had passed.

Porter attended a school taught by his aunt, then clerked in his uncle’s drugstore. In 1882 he went to Texas, where he worked on a ranch, in a general land office, and later as teller in the First National Bank in Austin. He began writing sketches at about the time of his marriage to Athol Estes in 1887, and in 1894 he started a humorous weekly, The Rolling Stone. When that venture failed, Porter joined the Houston Post as a reporter, columnist, and occasional cartoonist.

In February 1896 he was indicted for embezzlement of bank funds. Friends aided his flight to Honduras. News of his wife’s fatal illness, however, took him back to Austin, and lenient authorities did not press his case until after her death. When convicted, Porter received the lightest sentence possible, and in 1898 he entered the penitentiary at Columbus, Ohio; his sentence was shortened to three years and three months for good behaviour. As night druggist in the prison hospital, he could write to earn money for support of his daughter Margaret. His stories of adventure in the southwest U.S. and Central America were immediately popular with magazine readers, and when he emerged from prison W.S. Porter had become O. Henry.

In 1902 O. Henry arrived in New York—his “Bagdad on the Subway.” From December 1903 to January 1906 he produced a story a week for the New York World, writing also for magazines. His first book, Cabbages and Kings (1904), depicted fantastic characters against exotic Honduran backgrounds. Both The Four Million (1906) and The Trimmed Lamp (1907) explored the lives of the multitude of New York in their daily routines and searchings for romance and adventure. Heart of the West (1907) presented accurate and fascinating tales of the Texas range.

Then in rapid succession came The Voice of the City (1908), The Gentle Grafter (1908), Roads of Destiny (1909), Options (1909), Strictly Business (1910), and Whirligigs (1910). Whirligigs contains perhaps Porter’s funniest story, “The Ransom of Red Chief.”

Despite his popularity, O. Henry’s final years were marred by ill health, a desperate financial struggle, and alcoholism. A second marriage in 1907 was unhappy. After his death three more collected volumes appeared: Sixes and Sevens (1911), Rolling Stones (1912), and Waifs and Strays (1917). Later seven fugitive stories and poems, O. Henryana (1920), Letters to Lithopolis (1922), and two collections of his early work on the Houston Post, Postscripts (1923) and O. Henry Encore (1939), were published. Foreign translations and adaptations for other art forms, including films and television, attest his universal application and appeal.

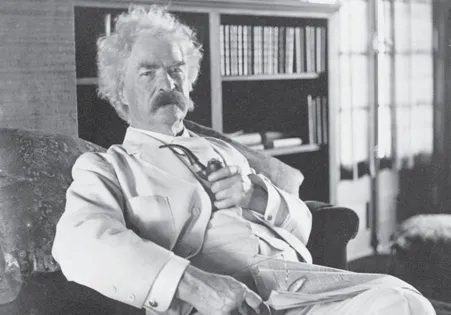

MARK TWAIN

(b. Nov. 30, 1835, Florida, Mo., U.S.—d. April 21, 1910, Redding, Conn.)

The American humorist, journalist, lecturer, and novelist Mark Twain acquired international fame for his travel narratives, especially The Innocents Abroad (1869), Roughing It (1872), and Life on the Mississippi (1883), and for his adventure stories of boyhood, especially The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885). A gifted raconteur, distinctive humorist, and irascible moralist, he transcended the apparent limitations of his origins to become a popular public figure and one of America’s best and most beloved writers.

Mark Twain. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. LC-USZ62-112728

APPRENTICESHIPS

Born Samuel Langhorne Clemens, Twain became a printers apprentice as a boy. That experience exposed him to the prewar sectional humorists. Having acquired a profession by age 17, Clemens left his hometown of Hannibal, Mo., in 1853 with some degree of self-sufficiency. For almost two decades he would be an itinerant labourer, trying many occupations. It was not until he was 37, he once remarked, that he woke up to discover he had become a “literary person.”

In February 1863 Clemens covered the legislative session in Carson City and wrote three letters for the Enterprise. He signed them “Mark Twain.” Apparently the mistranscription of a telegram misled Clemens to believe that the pilot Isaiah Sellers had died and that his cognomen was up for grabs. Clemens seized it. It would be several years before this pen name would acquire the firmness of a full-fledged literary persona, however. In the meantime, he was discovering by degrees what it meant to be a “literary person.”

Already he was acquiring a reputation outside the territory. Some of his articles and sketches had appeared in New York papers, and he became the Nevada correspondent for the San Francisco Morning Call. In 1864, after challenging the editor of a rival newspaper to a duel and then fearing the legal consequences for this indiscretion, he left Virginia City for San Francisco and became a full-time reporter for the Call. Finding that work tiresome, he began contributing to the Golden Era and the new literary magazine the Californian, edited by Bret Harte. After he published an article expressing his fiery indignation at police corruption in San Francisco, and after a man with whom he associated was arrested in a brawl, Clemens decided it prudent to leave the city for a time.

He went to the Tuolumne foothills to do some mining. It was there that he heard the story of a jumping frog. The story was widely known, but it was new to Clemens, and he took notes for a literary representation of the tale. When the humorist Artemus Ward invited him to contribute something for a book of humorous sketches, Clemens decided to write up the story. “Jim Smiley and His Jumping Frog” arrived too late to be included in the volume, but it was published in the New York Saturday Press in November 1865 and was subsequently reprinted throughout the country. “Mark Twain” had acquired sudden celebrity, and Sam Clemens was following in his wake.

LITERARY MATURITY

The next few years were important for Clemens. After he had finished writing the jumping-frog story but before it was published, he declared in a letter to his brother Orion that he had a “‘call’ to literature of a low order—i.e. humorous. It is nothing to be proud of,” he continued, “but it is my strongest suit.”

However much he might deprecate his calling, it appears that he was committed to making a professional career for himself. He continued to write for newspapers, traveling to Hawaii for the Sacramento Union and also writing for New York newspapers, but he apparently wanted to become something more than a journalist. He went on his first lecture tour, speaking mostly on the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) in 1866. It was a success, and for the rest of his life, though he found touring grueling, he knew he could take to the lecture platform when he needed money.

Meanwhile, he tried, unsuccessfully, to publish a book made up of his letters from Hawaii. His first book was in fact The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County and Other Sketches (1867), but it did not sell well. That same year, he moved to New York City, serving as the traveling correspondent for the San Francisco Alta California and for New York newspapers. He had ambitions to enlarge his reputation and his audience, and the announcement of a transatlantic excursion to Europe and the Holy Land provided him with just such an opportunity. The Alta paid the substantial fare in exchange for some 50 letters he would write concerning the trip. Eventually his account of the voyage was published as The Innocents Abroad (1869). It was a great success.

The trip abroad was fortuitous in another way. He met on the boat a young man named Charlie Langdon, who invited Clemens to dine with his family in New York and introduced him to his sister Olivia; the writer fell in love with her. Clemens’s courtship of Olivia Langdon, the daughter of a prosperous businessman from Elmira, N.Y., was an ardent one, conducted mostly through correspondence. They were married in February 1870. With financial assistance from Olivia’s father, Clemens bought a one-third interest in the Express of Buffalo, N.Y., and began writing a column for a New York City magazine, the Galaxy. A son, Langdon, was born in November 1870, but the boy was frail and would die of diphtheria less than two years later.

Clemens came to dislike Buffalo and hoped that he and his family might move to the Nook Farm area of Hartford, Conn. In the meantime, he worked hard on a book about his experiences in the West. Roughing It was published in February 1872 and sold well. The next month, Olivia Susan (Susy) Clemens was born in Elmira. Later that year, Clemens traveled to England. Upon his return, he began work with his friend Charles Dudley Warner on a satirical novel about political and financial corruption in the United States. The Gilded Age (1873) was remarkably well received, and a play based on the most amu...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: From the Civil War to 1914

- Chapter 2: American Naturalism

- Chapter 3: Novelists and Short-Story Writers During the World Wars

- Chapter 4: Drama and Poetry from 1914 to 1945

- Epilogue

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index