eBook - ePub

Ancient Egypt

From Prehistory to the Islamic Conquest

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ancient Egypt

From Prehistory to the Islamic Conquest

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Home to some of the most remarkable feats of engineering as well as awe-inspiring natural vistas, ancient Egypt was a land of great promise fulfilled. Its pyramids, writing systems, and art all predate the Islamic conquest and are symbols of the civilization's vitality. This volume invites readers to indulge in the splendors of ancient Egyptian culture and discover the traditions that have fired imaginations for generations. A detailed appendix profiles important sites throughout Egypt, many of which still contain remnants and artifacts that illustrate the import of this extraordinary civilization.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Ancient Egypt by Britannica Educational Publishing, Kathleen Kuiper in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Egyptian Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE STUDY OF ANCIENT EGYPT

Ancient Egyptian civilization developed in northeastern Africa in the 3rd millennium BC. Its many achievements, preserved in its art and monuments, hold a fascination that continues to grow as archaeological finds expose its secrets. The term ancient Egypt traditionally refers to northeastern Africa from its prehistory up to the Islamic conquest in the 7th century AD.

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN CIVILIZATION

Ancient Egypt can be thought of as an oasis in the desert of northeastern Africa, dependent on the annual inundation of the Nile River to support its agricultural population. The country’s chief wealth came from the fertile floodplain of the Nile valley, where the river flows between bands of limestone hills, and the Nile delta, in which it fans into several branches north of present-day Cairo. Between the floodplain and the hills is a variable band of low desert that supported a certain amount of game. The Nile was Egypt’s sole transportation artery.

LIFE IN ANCIENT EGYPT

The First Cataract of the Nile at Aswān, where the riverbed is turned into rapids by a belt of granite, was the country’s only well-defined boundary within a populated area. To the south lay the far less hospitable area of Nubia, in which the river flowed through low sandstone hills that in most regions left only a very narrow strip of cultivable land. Nubia was significant for Egypt’s periodic southward expansion and for access to products from farther south. West of the Nile was the arid Sahara, broken by a chain of oases some 125 to 185 miles (200 to 300 kilometres) from the river and lacking in all other resources except for a few minerals. The eastern desert, between the Nile and the Red Sea, was more important, for it supported a small nomadic population and desert game, contained numerous mineral deposits, including gold, and was the route to the Red Sea.

To the northeast was the Isthmus of Suez. It offered the principal route for contact with Sinai, from which came turquoise and possibly copper, and with southwestern Asia, Egypt’s most important area of cultural interaction, from which were received stimuli for technical development and cultivars for crops. Immigrants and ultimately invaders crossed the isthmus into Egypt, attracted by the country’s stability and prosperity. From the late 2nd millennium BC onward, numerous attacks were made by land and sea along the eastern Mediterranean coast.

At first, relatively little cultural contact came by way of the Mediterranean Sea, but from an early date Egypt maintained trading relations with the Lebanese port of Byblos (present-day Jbail). Egypt needed few imports to maintain basic standards of living, but good timber was essential and not available within the country, so it usually was obtained from Lebanon. Minerals such as obsidian and lapis lazuli were imported from as far afield as Anatolia and Afghanistan.

Agriculture centred on the cultivation of cereal crops, chiefly emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccum) and barley (Hordeum vulgare). The fertility of the land and general predictability of the inundation ensured very high productivity from a single annual crop. This productivity made it possible to store large surpluses against crop failures and also formed the chief basis of Egyptian wealth, which was, until the creation of the large empires of the 1st millennium BC, the greatest of any state in the ancient Middle East.

Basin irrigation was achieved by simple means, and multiple cropping was not feasible until much later times, except perhaps in the lakeside area of Al-Fayyūm. As the river deposited alluvial silt, raising the level of the floodplain, and land was reclaimed from marsh, the area available for cultivation in the Nile valley and delta increased, while pastoralism declined slowly. In addition to grain crops, fruit and vegetables were important, the latter being irrigated year-round in small plots; fish was also vital to the diet. Papyrus, which grew abundantly in marshes, was gathered wild and in later times was cultivated. It may have been used as a food crop, and it certainly was used to make rope, matting, and sandals. Above all, it provided the characteristic Egyptian writing material, which, with cereals, was the country’s chief export in Late period Egyptian and then Greco-Roman times.

Cattle may have been domesticated in northeastern Africa. The Egyptians kept many as draft animals and for their various products, showing some of the interest in breeds and individuals that is found to this day in the Sudan and eastern Africa. The donkey, which was the principal transport animal (the camel did not become common until Roman times), was probably domesticated in the region. The native Egyptian breed of sheep became extinct in the 2nd millennium BC and was replaced by an Asiatic breed. Sheep were primarily a source of meat; their wool was rarely used. Goats were more numerous than sheep. Pigs were also raised and eaten. Ducks and geese were kept for food, and many of the vast numbers of wild and migratory birds found in Egypt were hunted and trapped. Desert game, principally various species of antelope and ibex, were hunted by the elite; it was a royal privilege to hunt lions and wild cattle. Pets included dogs, which were also used for hunting, cats (domesticated in Egypt), and monkeys. In addition, the Egyptians had a great interest in, and knowledge of, most species of mammals, birds, reptiles, and fish in their environment.

Most Egyptians were probably descended from settlers who moved to the Nile valley in prehistoric times, with population increase coming through natural fertility. In various periods there were immigrants from Nubia, Libya, and especially the Middle East. They were historically significant and also may have contributed to population growth, but their numbers are unknown. Most people lived in villages and towns in the Nile valley and delta. Dwellings were normally built of mud brick and have long since disappeared beneath the rising water table or beneath modern town sites, thereby obliterating evidence for settlement patterns. In antiquity, as now, the most favoured location of settlements was on slightly raised ground near the riverbank, where transport and water were easily available and flooding was unlikely. Until the 1st millennium BC, Egypt was not urbanized to the same extent as Mesopotamia. Instead, a few centres, notably Memphis and Thebes, attracted population and particularly the elite, while the rest of the people were relatively evenly spread over the land. The size of the population has been estimated as having risen from 1 to 1.5 million in the 3rd millennium BC to perhaps twice that number in the late 2nd millennium and 1st millennium BC. (Much higher levels of population were reached in Greco-Roman times.)

Nearly all of the people were engaged in agriculture and were probably tied to the land. In theory all the land belonged to the king, although in practice those living on it could not easily be removed, and some categories of land could be bought and sold. Land was assigned to high officials to provide them with an income, and most tracts required payment of substantial dues to the state, which had a strong interest in keeping the land in agricultural use. Abandoned land was taken back into state ownership and reassigned for cultivation. The people who lived on and worked the land were not free to leave and were obliged to work it, but they were not slaves. Most paid a proportion of their produce to major officials. Free citizens who worked the land on their own behalf did emerge. Terms applied to them tended originally to refer to poor people, but these agriculturalists were probably not poor.

Slavery was never common, being restricted to captives and foreigners or to people who were forced by poverty or debt to sell themselves into service. Slaves sometimes even married members of their owners’ families, so that in the long term those belonging to households tended to be assimilated into free society. In the New Kingdom (from about 1539 to 1075 BC), large numbers of captive slaves were acquired by major state institutions or incorporated into the army. Punitive treatment of foreign slaves or of native fugitives from their obligations included forced labour, exile (in, for example, the oases of the western desert), or compulsory enlistment in dangerous mining expeditions. Even nonpunitive employment such as quarrying in the desert was hazardous. The official record of one expedition shows a mortality rate of more than 10 percent.

Just as the Egyptians optimized agricultural production with simple means, their crafts and techniques, many of which originally came from Asia, were raised to extraordinary levels of perfection. The Egyptians’ most striking technical achievement, massive stone building, also exploited the potential of a centralized state to mobilize a huge labour force, which was made available by efficient agricultural practices. Some of the technical and organizational skills involved were remarkable. The construction of the great pyramids of the 4th dynasty (c. 2575–c. 2465 BC) has yet to be fully explained and would be a major challenge to this day. This expenditure of skill contrasts with sparse evidence of an essentially neolithic way of living for the rural population of the time, while the use of flint tools persisted even in urban environments at least until the late 2nd millennium BC. Metal was correspondingly scarce, much of it being used for prestige rather than everyday purposes.

In urban and elite contexts, the Egyptian ideal was the nuclear family, but, on the land and even within the central ruling group, there is evidence for extended families. Egyptians were monogamous, and the choice of partners in marriage, for which no formal ceremony or legal sanction is known, did not follow a set pattern. Consanguineous marriage was not practiced during the Dynastic period, except for the occasional marriage of a brother and sister within the royal family, and that practice may have been open only to kings or heirs to the throne. Divorce was in theory easy, but it was costly. Women had a legal status only marginally inferior to that of men. They could own and dispose of property in their own right, and they could initiate divorce and other legal proceedings. They hardly ever held administrative office but increasingly were involved in religious cults as priestesses or “chantresses.” Married women held the title “mistress of the house,” the precise significance of which is unknown. Lower down the social scale, they probably worked on the land as well as in the house.

The uneven distribution of wealth, labour, and technology was related to the only partly urban character of society, especially in the 3rd millennium BC. The country’s resources were not fed into numerous provincial towns but instead were concentrated to great effect around the capital—itself a dispersed string of settlements rather than a city—and focused on the central figure in society, the king. In the 3rd and early 2nd millennia, the elite ideal, expressed in the decoration of private tombs, was manorial and rural. Not until much later did Egyptians develop a more pronouncedly urban character.

THE KING AND IDEOLOGY: ADMINISTRATION, ART, AND WRITING

In cosmogonical terms, Egyptian society consisted of a descending hierarchy of the gods, the king, the blessed dead, and humanity (by which was understood chiefly the Egyptians). Of these groups, only the king was single, and hence he was individually more prominent than any of the others. A text that summarizes the king’s role states that he “is on earth for ever and ever, judging humankind and propitiating the gods, and setting order [ma‘at, a central concept] in place of disorder. He gives offerings to the gods and mortuary offerings to the spirits [the blessed dead].” The king was imbued with divine essence, but not in any simple or unqualified sense. His divinity accrued to him from his office and was reaffirmed through rituals, but it was vastly inferior to that of major gods. He was god rather than human by virtue of his potential, which was immeasurably greater than that of any human being. To humanity, he manifested the gods on earth, a conception that was elaborated in a complex web of metaphor and doctrine.

Less directly, he represented humanity to the gods. The text quoted above also gives great prominence to the dead, who were the object of a cult for the living and who could intervene in human affairs; in many periods the chief visible expenditure and focus of display of non-royal individuals, as of the king, was on provision for the tomb and the next world. Egyptian kings are commonly called pharaohs, following the usage of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament). The term pharaoh, however, is derived from the Egyptian per ‘aa (“great estate”) and dates to the designation of the royal palace as an institution. This term for palace was used increasingly from about 1400 BC as a way of referring to the living king; in earlier times it was rare.

Rules of succession to the kingship are poorly understood. The common conception that the heir to the throne had to marry his predecessor’s oldest daughter has been disproved; kingship did not pass through the female line. The choice of queen seems to have been free. Often the queen was a close relative of the king, but she also might be unrelated to him. In the New Kingdom, for which evidence is abundant, each king had a queen with distinctive titles, as well as a number of minor wives.

Sons of the chief queen seem to have been the preferred successors to the throne, but other sons could also become king. In many cases the successor was the eldest (surviving) son, and such a pattern of inheritance agrees with more general Egyptian values, but often he was some other relative or was completely unrelated. New Kingdom texts describe, after the event, how kings were appointed heirs either by their predecessors or by divine oracles, and such may have been the pattern when there was no clear successor. Dissent and conflict are suppressed from public sources. From the Late period (664–332 BC), when sources are more diverse and patterns less rigid, numerous usurpations and interruptions to the succession are known. They probably had many forerunners.

The king’s position changed gradually from that of an absolute monarch at the centre of a small ruling group made up mostly of his kin to that of the head of a bureaucratic state—in which his rule was still absolute—based on officeholding and, in theory, on free competition and merit. By the 5th dynasty, fixed institutions had been added to the force of tradition and the regulation of personal contact as brakes on autocracy, but the charismatic and superhuman power of the king remained vital.

The elite of administrative office-holders received their positions and commissions from the king, whose general role as judge over humanity they put into effect. They commemorated their own justice and concern for others, especially their inferiors, and recorded their own exploits and ideal conduct of life in inscriptions for others to see. Thus, the position of the elite was affirmed by reference to the king, to their prestige among their peers, and to their conduct toward their subordinates, justifying to some extent the fact that they—and still more the king—appropriated much of the country’s production.

These attitudes and their potential dissemination through society counterbalanced inequality, but how far they were accepted cannot be known. The core group of wealthy officeholders numbered at most a few hundred, and the administrative class of minor officials and scribes, most of whom could not afford to leave memorials or inscriptions, perhaps 5,000. With their dependents, these two groups formed perhaps 5 percent of the early population. Monuments and inscriptions commemorated no more than one in a thousand people.

According to royal ideology, the king appointed the elite on the basis of merit, and in ancient conditions of high mortality the elite had to be open to recruits from outside. There was, however, also an ideal that a son should succeed his father. In periods of weak central control this principle predominated, and in the Late period the whole society became more rigid and stratified.

Writing was a major instrument in the centralization of the Egyptian state and its self-presentation. The two basic types of writing—hieroglyphs, which were used for monuments and display, and the cursive form known as hieratic—were invented at much the same time in late predynastic Egypt (c. 3000 BC). Writing was chiefly used for administration, and until about 2650 BC no continuous texts are preserved; the only extant literary texts written before the early Middle Kingdom (c. 1950 BC) seem to have been lists of important traditional information and possibly medical treatises. The use and potential of writing were restricted both by the rate of literacy, which was probably well below 1 percent, and by expectations of what writing might do.

Hieroglyphic writing was publicly identified with Egypt. Perhaps because of this association with a single powerful state, its language, and its culture, Egyptian writing was seldom adapted to write other languages; in this it contrasts with the cuneiform script of the relatively uncentralized, multilingual Mesopotamia. Nonetheless, Egyptian hieroglyphs probably served in the middle of the 2nd millennium BC as the model from which the alphabet, ultimately the most widespread of all writing systems, evolved.

The dominant visible legacy of ancient Egypt is in works of architecture and representational art. Until the Middle Kingdom, most of these were mortuary, namely royal tomb complexes, including pyramids and mortuary temples, and private tombs. There were also temples dedicated to the cult of the gods throughout the country, but most of these were modest structures. From the beginning of the New Kingdom, temples of the gods became the principal monuments. Royal palaces and private houses, which are very little known, were less important.

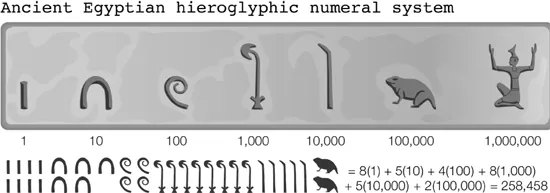

Egyptian hieroglyphic numerals. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

Temples and tombs were ideally executed in stone with relief decoration on their walls and were filled with stone and wooden statuary, inscribed and decorate...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Study of Ancient Egypt

- Chapter 2: The Early Period

- Chapter 3: The Old and Middle Kingdoms

- Chapter 4: The New Kingdom and the Third Intermediate Period

- Chapter 5: The Late Period and Beyond

- Chapter 6: Roman and Byzantine Egypt

- Chapter 7: Egyptian Religion

- Chapter 8: Egyptian Language and Writing

- Chapter 9: Egyptian Art and Architecture

- Chapter 10: Egyptomania

- Appendix: Selected Sites

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index