- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Battling and Managing Disease

About this book

As the world's population expands, so too does the risk of communicable disease and global pandemics. Consequently, healthcare has assumed a greater centrality in the public consciousness both in the United States and around the world. With various national and international organizations dedicated to epidemiological research and disease control, societal welfare has become an increasingly significant aspect of public policy. The historical, legal, and scientific factors that form the basis of public health locally and globally are the subjects of this relevant and revealing volume.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

MedicineSubtopic

EpidemiologyCHAPTER 1

HEALTH AND DISEASE IN SOCIETY: HISTORICAL AND INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES

Health and disease have long been important human concerns. Indeed, preventing disease and prolonging life have formed the basis for the practice of medicine for thousands of years. A major area of interest in human health that has persisted throughout history has been the impact of disease within the context of society. In the modern era, the significance of this relationship is embodied by measures of disease burden within individual communities and countries, as well as globally. Communities that carry a high burden of disease, which entails a high rate of premature mortality, with many people living in poor health, tend to be less economically productive than communities that carry a comparatively low disease burden. As a result, finding ways to control disease is vital in the context of maintaining not only the health of individuals within communities but also the economic productivity and stability of communities and countries.

Public health—which encompasses disease prevention and promotion of physical and mental health, sanitation, personal hygiene, control of infection, and organization of health services—is fundamental in minimizing the impact of disease in society. From the normal human interactions involved in dealing with the many problems of social life, there has emerged a recognition of the importance of community action in the promotion of health and in the prevention and treatment of disease. This is expressed in the concept of public health.

The practice of public health draws heavily on medical science and philosophy, and concentrates especially on manipulating and controlling the environment for the benefit of society. Therefore, it is concerned primarily with housing, water supplies, and food and with ensuring that the necessary resources, including physicians and medicines, are made available to the public. Noxious agents can be introduced into housing and into food and water supplies through farming, fertilizers, inadequate sewage disposal and drainage, construction, defective heating and ventilating systems, machinery, and toxic chemicals. Public health medicine, however, is only one part of the greater enterprise of preserving and improving the health of communities. For example, physicians and therapists cooperate with diverse groups, ranging from architects and builders to sanitary engineers to factory and food inspectors, psychologists and sociologists, chemists, physicists, and toxicologists. Occupational medicine is concerned with the health, safety, and welfare of persons in the workplace. This field may be viewed as a specialized part of public health medicine since its aim is to reduce risks in the work environment.

The venture of preserving, maintaining, and actively promoting public health requires special methods of information-gathering (epidemiology) and corporate arrangements to act upon significant findings and to put them into practice. Statistics collected by epidemiologists attempt to describe and explain the occurrence of disease in a population by correlating factors such as diet, environment, radiation, or cigarette smoking with the incidence and prevalence of disease. The government, through laws and regulations, creates agencies to oversee and formally inspect water supplies, food processing, sewage treatment, drains, air contamination, and pollution. Governments also are concerned with the control of epidemic infections by means of enforced quarantine and isolation—for example, the health control that takes place at seaports and airports in an attempt to assure that infectious diseases are not brought into a country.

Various public health agencies have been established to help control and monitor disease within societies, on both national and international levels. For example, the United Kingdom’s Public Health Act of 1848 established a special public health ministry for England and Wales. In the United States, public health is studied and coordinated on a national level by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Internationally, the World Health Organization (WHO) plays an equivalent role. WHO is especially important in providing assistance for the implementation of organizational and administrative methods of handling problems associated with health and disease in developing countries worldwide. Within these countries, health problems, limitations of resources, education of health personnel, and other factors must be taken into account in designing health service systems.

Advances in science and medicine in developed countries, including the generation of vaccines and antibiotics, have been fundamental in bringing vital aid to countries afflicted by a high burden of disease. Yet, despite the expansion of resources and improvements in the mobilization of these resources to the most severely afflicted areas, the incidence of preventable disease and of neglected tropical disease remains exceptionally high worldwide. Reducing the impact and prevalence of these diseases is a major goal of international public health. The persistence of such diseases in the world, however, serves as an important indication of the difficulties that health organizations and societies continue to confront today.

HISTORY OF PUBLIC HEALTH

A review of the historical development of public health, which began in ancient times, emphasizes how various public health concepts have evolved. Historical public health measures included quarantine of leprosy victims in the Middle Ages and efforts to improve sanitation following the 14th-century plague epidemics. Population increases in Europe brought with them increased awareness of infant deaths and a proliferation of hospitals. These developments, in turn, led to the establishment of modern public health agencies and organizations, designed to control disease within communities and to oversee the availability and distribution of medicines.

BEGINNINGS IN ANTIQUITY

Most of the world’s primitive people have practiced cleanliness and personal hygiene, often for religious reasons, including, apparently, a wish to be pure in the eyes of their gods. The Old Testament, for example, has many adjurations and prohibitions about clean and unclean living. Religion, law, and custom were inextricably interwoven. For thousands of years primitive societies looked upon epidemics as divine judgments on the wickedness of humankind. The idea that pestilence is due to natural causes, such as climate and physical environment, developed gradually. This great advance in thought took place in Greece during the 5th and 4th centuries BCE and represented the first attempt at a rational, scientific theory of disease causation. The association between malaria and swamps, for example, was established very early (503–403 BCE), even though the reasons for the association were obscure. In the book Airs, Waters, and Places, thought to have been written by Greek physician Hippocrates in the 5th or 4th century BCE, the first systematic attempt was made to set forth a causal relationship between human diseases and the environment. Until the new sciences of bacteriology and immunology emerged well into the 19th century, this book provided a theoretical basis for the comprehension of endemic disease (that persisting in a particular locality) and epidemic disease (that affecting a number of people within a relatively short period).

THE MIDDLE AGES

In terms of disease, the Middle Ages can be regarded as beginning with the plague of 542 and ending with the Black Death (bubonic plague) of 1348. Diseases in epidemic proportions included leprosy, bubonic plague, smallpox, tuberculosis, scabies, erysipelas, anthrax, trachoma, sweating sickness, and dancing mania. The isolation of persons with communicable diseases first arose in response to the spread of leprosy. This disease became a serious problem in the Middle Ages and particularly in the 13th and 14th centuries.

The Black Death reached the shores of southern Europe from the Middle East in 1348 and in three years swept throughout Europe. The chief method of combating plague was to isolate known or suspected cases as well as persons who had been in contact with them. The period of isolation at first was about 14 days and gradually was increased to 40 days. Stirred by the Black Death, public officials created a system of sanitary control to combat contagious diseases, using observation stations, isolation hospitals, and disinfection procedures. Major efforts to improve sanitation included the development of pure water supplies, garbage and sewage disposal, and food inspection. These efforts were especially important in the cities, where people lived in crowded conditions in a rural manner with many animals around their homes.

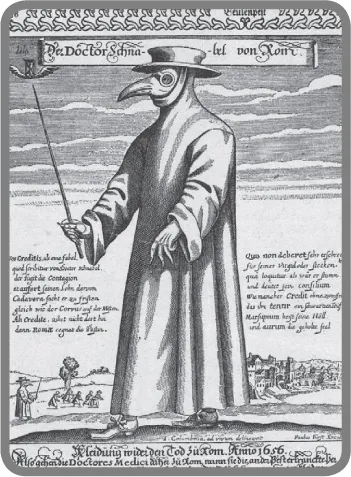

During the Medieval period and the Renaissance, plague doctors often wore protective clothing like this outfit. The beak mask held spices thought to purify air; the wand was used to avoid touching patients. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

During the Middle Ages a number of first steps in public health were made: attempts to cope with the unsanitary conditions of the cities and, by means of quarantine, to limit the spread of disease; the establishment of hospitals; and provision of medical care and social assistance.

THE RENAISSANCE

Centuries of technological advance culminated in the 16th and 17th centuries in a number of scientific accomplishments. Educated leaders of the time recognized that the political and economic strength of the state required that the population maintain good health. No national health policies were developed in England or on the Continent, however, because the government lacked the knowledge and administrative machinery to carry out such policies. As a result, public health problems continued to be handled on a local community basis, as they had been in medieval times.

Scientific advances of the 16th and 17th centuries laid the foundations of anatomy and physiology. Observation and classification made possible the more precise recognition of diseases. The idea that microscopic organisms might cause communicable diseases had begun to take shape.

Among the early pioneers in public health medicine was John Graunt, who in 1662 published a book of statistics, which had been compiled by parish and municipal councils, that gave numbers for deaths and sometimes suggested their causes. Inevitably the numbers were inaccurate but a start was made in epidemiology.

NATIONAL DEVELOPMENTS IN THE 18TH AND 19TH CENTURIES

Nineteenth-century movements to improve sanitation occurred simultaneously in several European countries and were built upon foundations laid in the period between 1750 and 1830. From about 1750 the population of Europe increased rapidly, and with this increase came a heightened awareness of the large numbers of infant deaths and of the unsavoury conditions in prisons and in mental institutions.

This period also witnessed the beginning and the rapid growth of hospitals. Hospitals founded in the United Kingdom, as the result of voluntary efforts by private citizens, helped to create a pattern that was to become familiar in public health services. First, a social evil is recognized and studies are undertaken through individual initiative. These efforts mold public opinion and attract governmental attention. Finally, such agitation leads to governmental action.

This era was also characterized by efforts to educate people in health matters. In 1852 British physician Sir John Pringle published a book that discussed ventilation in barracks and the provision of latrines. Two years earlier he had written about jail fever (now thought to be typhus), and again he emphasized the same needs as well as personal hygiene. In 1754 James Lind, who had worked as a surgeon in the British Navy, published a treatise on scurvy, a disease caused by a lack of vitamin C.

As the Industrial Revolution developed, the health and welfare of the workers deteriorated. In England, where the Industrial Revolution and its bad effects on health were first experienced, there arose in the 19th century a movement toward sanitary reform that finally led to the establishment of public health institutions. Between 1801 and 1841 the population of London doubled, while that of Leeds nearly tripled. With such growth there also came rising death rates. Between 1831 and 1844 the death rate per thousand increased in Birmingham from 14.6 to 27.2; in Bristol, from 16.9 to 31; and in Liverpool, from 21 to 34.8. These figures were the result of an increase in the urban population that far exceeded available housing and of the subsequent development of conditions that led to widespread disease and poor health.

Around the beginning of the 19th century humanitarians and philanthropists in England worked to educate the population and the government on problems associated with population growth, poverty, and epidemics. In 1798 English economist and demographer Thomas Malthus wrote about population growth, its dependence on food supply, and the control of breeding by contraceptive methods. The utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham propounded the idea of the greatest good of the greatest number as a yardstick against which the morality of certain actions might be judged. British physician Thomas Southwood Smith founded the Health of Towns Association in 1839, and by 1848 he served as a member of the new government department, then called the General Board of Health. He published reports on quarantine, cholera, yellow fever, and the benefits of sanitary improvements.

The Poor Law Commission, created in 1834, explored problems of community health and suggested means for solving them. Its report, in 1838, argued that “the expenditures necessary to the adoption and maintenance of measures of prevention would ultimately amount to less than the cost of the disease now constantly engendered.” Sanitary surveys proved that a relationship exists between communicable disease and filth in the environment, and it was said that safeguarding public health is the province of the engineer rather than of the physician.

The Public Health Act of 1848 established a General Board of Health to furnish guidance and aid in sanitary matters to local authorities, whose earlier efforts had been impeded by lack of a central authority. The board had authority to establish local boards of health and to investigate sanitary conditions in particular districts. Since this time several public health acts have been passed to regulate sewage and refuse disposal, the housing of animals, the water supply, prevention and control of disease, registration and inspection of private nursing homes and hospitals, the notification of births, and the provision of maternity and child welfare services.

Advances in public health in England had a strong influence in the United States, where one of the basic problems, as in England, was the need to create effective administrative mechanisms for the supervision and regulation of community health. In America recurrent epidemics of yellow fever, cholera, smallpox, typhoid, and typhus made the need for effective public health administration a matter of urgency. The so-called Shattuck report, published in 1850 by the Massachusetts Sanitary Commission, reviewed the serious health problems and grossly unsatisfactory living conditions in Boston. Its recommendations included an outline for a sound...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Health and Disease in Society: Historical and International Perspectives

- Chapter 2: Public Health in Developed and Developing Countries

- Chapter 3: Health Care in Society

- Chapter 4: Legal Aspects of Health Care

- Chapter 5: Defining Health and Disease: Noncommunicable Disease

- Chapter 6: Defining Health and Disease: Communicable Disease

- Chapter 7: Major Diseases of Concern in Modern Society

- Chapter 8: Occupational Disease

- Chapter 9: Medicine and Research in the Health of Society

- Chapter 10: Disease Prevention and Progress in Public Health

- Conclusion

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Battling and Managing Disease by Britannica Educational Publishing, Kara Rogers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Epidemiology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.