eBook - ePub

The Geography of China

Sacred and Historic Places

Britannica Educational Publishing, Kenneth Pletcher

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Geography of China

Sacred and Historic Places

Britannica Educational Publishing, Kenneth Pletcher

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

With its flourishing metropolises, China has come to be identified with urban life and rapid technological advancement. Yet much of its landscape also boasts communities sustained by wondrous natural resources, which contribute to the scenic and spiritual beauty of the nation as well as its economic productivity. Within these pages, readers are invited to tour China's cities, villages, and countryside. They'll visit the natural and manmade landmarks that reveal as much about the history of this vast nation as its geography.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Geography of China by Britannica Educational Publishing, Kenneth Pletcher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Chinese History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

GEOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW

Within China’s boundaries exists a highly diverse and complex country. Its topography encompasses the highest and one of the lowest places on Earth, and its relief varies from nearly impenetrable mountainous terrain to vast coastal lowlands.

RELIEF

Broadly speaking, the relief of China is high in the west and low in the east; consequently, the direction of flow of the major rivers is generally eastward. The surface may be divided into three steps, or levels. The first level is represented by the Plateau of Tibet, which is located in both the Tibet Autonomous Region and the province of Qinghai and which, with an average elevation of well over 13,000 feet (4,000 m) above sea level, is the loftiest highland area in the world. The western part of this region, the Qiangtang, has an average height of 16,500 feet (5,000 m) and is known as the “roof of the world.”

The second step lies to the north of the Kunlun and Qilian mountains and (farther south) to the east of the Qionglai and Daliang ranges. There the mountains descend sharply to heights of between 6,000 and 3,000 feet (1,800 and 900 m), after which basins intermingle with plateaus. This step includes the Mongolian Plateau, the Tarim Basin, the Loess Plateau (loess is a yellow-gray dust deposited by the wind), the Sichuan Basin, and the Yunnan-Guizhou (Yungui) Plateau.

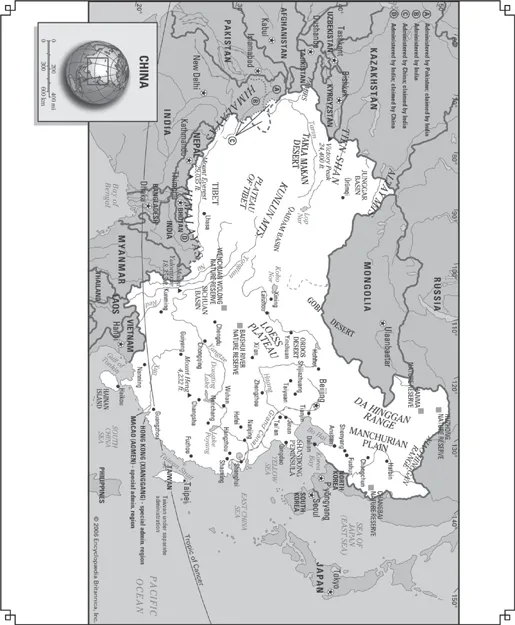

This map shows China and its special administrative regions.

The third step extends from the east of the Dalou, Taihang, and Wu mountain ranges and from the eastern perimeter of the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau to the China Sea. Almost all of this area is made up of hills and plains lying below 1,500 feet (450 m).

The most remarkable feature of China’s relief is the vast extent of its mountain chains; the mountains, indeed, have exerted a tremendous influence on the country’s political, economic, and cultural development. By rough estimate, about one-third of the total area of China consists of mountains. China has some of the world’s tallest mountains and the world’s highest and largest plateau, in addition to possessing extensive coastal plains. The five major landforms—mountain, plateau, hill, plain, and basin—are all well represented. China’s complex natural environment and rich natural resources are closely connected with the varied nature of its relief.

The topography of China is marked by many splendours. Mount Everest (Qomolangma Feng), situated on the border between Tibet and Nepal, is the highest peak in the world, at an elevation of 29,035 feet (8,850 m). By contrast, the lowest part of the Turfan Depression in the Uygur Autonomous Region of Xinjiang—Lake Ayding—is 508 feet (155 m) below sea level. The coast of China contrasts greatly between South and North. To the south of the bay of Hangzhou, the coast is rocky and indented with many harbours and offshore islands. To the north, except along the Shandong and Liaodong peninsulas, the coast is sandy and flat.

China is prone to intense seismic activity throughout much of the country. The main source of this geologic instability is the result of the constant northward movement of the Indian tectonic plate beneath southern Asia, which has thrust up the towering mountains and high plateaus of the Chinese southwest. Throughout its history China has experienced hundreds of massive earthquakes that collectively have killed millions of people. Two in the 20th century alone—in eastern Gansu province (1920) and in the city of Tangshan, eastern Hebei province (1976)—caused some 250,000 deaths each, and a quake in east-central Sichuan province in 2008 killed tens of thousands and devastated a wide area.

China’s physical relief has dictated its development in many respects. The civilization of Han Chinese originated in the southern part of the Loess Plateau, and from there it extended outward until it encountered the combined barriers of relief and climate. The long, protruding strip of land, commonly known as the Gansu, or Hexi, Corridor, illustrates this fact. South of the corridor is the Plateau of Tibet, which was too high and too cold for the Chinese to gain a foothold. North of the corridor is the Gobi Desert, which also formed a barrier. Consequently, Chinese civilization was forced to spread along the corridor, where melting snow and ice in the Qilian Mountains provided water for oasis farming. The westward extremities of the corridor became the meeting place of the ancient East and West.

Thus, for a long time the ancient political centre of China was located along the lower reaches of the Huang He (Yellow River). Because of topographical barriers, however, it was difficult for the central government to gain complete control over the entire country, except when an unusually strong dynasty was in power. In many instances the Sichuan Basin—an isolated region in southwestern China, about twice the size of Scotland, that is well protected by high mountains and self-sufficient in agricultural products—became an independent kingdom. A comparable situation often arose in the Tarim Basin in the northwest. Linked to the rest of China only by the Gansu Corridor, this basin is even remoter than the Sichuan, and, when the central government was unable to exert its influence, oasis states were established; only the three strong dynasties—the Han (206 BCE—220 CE), the Tang (618–907 CE), and the Qing, or Manchu (1644–1911/12)—were capable of controlling the region.

Apart from the three elevation zones already mentioned, it is possible—on the basis of geologic structure, climatic conditions, and differences in geomorphologic development—to divide China into three major topographic regions: the eastern, southwestern, and northwestern zones.

THE EASTERN REGION

The eastern zone is shaped by the rivers, which have eroded landforms in some parts and have deposited alluvial plains in others; its climate is monsoonal (characterized by seasonal rain-bearing winds). Topographically the most complex of the three regions, it can be subdivided into ten second-order geographic divisions.

THE NORTHEAST PLAIN

The Northeast Plain (also known as the Manchurian Plain and the Sung-liao Plain) is located in China’s Northeast, the region formerly known as Manchuria. It is bordered to the west and north by the Da Hinggan (Greater Khingan) Range and to the east by the Xiao Hinggan (Lesser Khingan) Range. An undulating plain split into northern and southern halves by a low divide rising from 500 to 850 feet (150 to 260 m), it is drained in its northern part by the Sungari River and tributaries and in its southern part by the Liao River. Most of the area has an erosional rather than a depositional surface, but it is covered with a deep soil. The plain has an area of about 135,000 square miles (350,000 square kilometres). Its basic landscapes are forest-steppe, steppe, meadow-steppe, and cultivated land; its soils are rich and black, and it is a famous agricultural region. The river valleys are wide and flat with a series of terraces formed by deposits of silt. During the flood season the rivers inundate extensive areas.

Da Hinggan (Greater Khingan) Range, southeast of Hailar, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China. Richard Harrington/Miller Services Ltd.

THE CHANGBAI MOUNTAINS

To the southeast of the Northeast Plain is a series of ranges comprising the Changbai, Zhangguangcai, and Wanda mountains, which in Chinese are collectively known as the Changbai Shan, or “Forever White Mountains.” Broken by occasional open valleys, they reach elevations mostly between 1,500 and 3,000 feet (450 and 900 m). In some parts the scenery is characterized by rugged peaks and precipitous cliffs. The highest peak is the volcanic cone of Mount Baitou (9,003 feet [2,744 m]), which has a beautiful crater lake at its snow-covered summit. As one of the major forest areas of China, the region is the source of many valuable furs and famous medicinal herbs. Cultivation is generally limited to the valley floors.

THE NORTH CHINA PLAIN

Comparable in size to the Northeast Plain, most of the North China Plain lies at elevations below 160 feet (50 m), and the relief is monotonously flat. It was formed by enormous sedimentary deposits brought down by the Huang He and Huai River from the Loess Plateau; the Quaternary deposits alone (i.e., those from the past 2.6 million years) reach thicknesses of 2,500 to 3,000 feet (760 to 900 m). The river channels, which are higher than the surrounding locality, form local water divides, and the areas between the channels are depressions in which lakes and swamps are found. In particularly low and flat areas, the underground water table often fluctuates from 5 to 6.5 feet (1.5 to 2 m), forming meadow swamps and, in some places, resulting in saline soils. A densely populated area that has long been under settlement, the North China Plain has the highest proportion of land under cultivation of any region in China.

THE LOESS PLATEAU

The Loess Plateau is a vast 154,000 square miles (400,000 square km) and forms a unique region of hills clad in loess (dry, powdery, wind-blown soil) and barren mountains between the North China Plain and the deserts of the west. In the north the Great Wall of China forms the boundary, while the southern limit is the Qin Mountains in Shaanxi province. The average surface elevation is roughly 4,000 feet (1,200 m), but individual ranges of bedrock are higher, reaching 9,825 feet (2,995 m) in the Liupan Mountains. Most of the plateau is covered with loess to thicknesses of 165 to 260 feet (50 to 80 m). In northern Shaanxi and eastern Gansu provinces, the loess may reach much greater thicknesses. The loess is particularly susceptible to erosion by water, and ravines and gorges crisscross the plateau. It has been estimated that ravines cover approximately half the entire region, with erosion reaching depths of 300 to 650 feet (90 to 200 m).

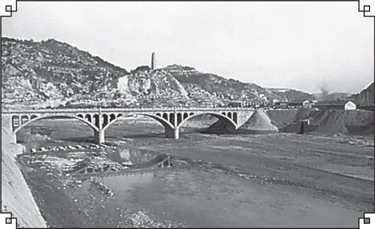

The Yan River at Yan’an, Shaanxi province, China, in the eastern portion of the Loess Plateau. A. Topping—Rapho/Photo Researchers

THE SHANDONG HILLS

The Shandong Hills are basically composed of extremely ancient crystalline shales and granites of early Precambrian age (i.e., older than about 2.5 billion years) and of somewhat younger sedimentary rocks dating to about 540–420 million years ago. Faults have played a major role in creating the present relief, and, as a result, many hills are horsts (blocks of Earth’s crust uplifted along faults), while the valleys have been formed by grabens (blocks of Earth’s crust that have been thrust down along faults). The Jiaolai Plain divides this region into two parts. The eastern part is lower, lying at elevations averaging below 1,500 feet (450 m), with only certain peaks and ridges rising to 2,500 feet and (rarely) to 3,000 feet (900 m); the highest point, Mount Lao, reaches 3,714 feet (1,132 m). The western part is slightly higher, rising to 5,000 feet (1,524 m) at Mount Tai, one of China’s most sacred mountains. The Shandong Hills meet the sea along a rocky and indented shoreline.

THE QIN MOUNTAINS

The Qin (conventional Tsinling) Mountains in Shaanxi province are the greatest chain of mountains east of the Plateau of Tibet. The mountain chain consists of a high and rugged barrier extending from Gansu to Henan; geographers use a line between the chain and the Huai River to divide China proper into two parts—North and South. The elevation of the mountains varies from 3,000 to 10,000 feet (900 to 3,000 m). The western part is higher, with the highest peak, Mount Taibai, rising to 12,359 feet (3,767 m). The Qin Mountains consist of a series of parallel ridges, all running roughly west-east, separated by a maze of ramifying valleys whose canyon walls often rise sheer to a height of 1,000 feet (300 m) above the valley streams.

THE SICHUAN BASIN

The Sichuan Basin is one of the most attractive geographical regions of China. It is surrounded by mountains, which are higher in the west and north. Protected against the penetration of cold northern winds, the basin is much warmer in the winter than are the more southerly plains of southeast China. Except for the Chengdu Plain, the region is hilly. The relief of the basin’s eastern half consists of numerous folds, forming a series of ridges and valleys that trend northeast to southwest. The lack of arable land has obliged farmers to cultivate the slopes of the hills, on which they have built terraces that frequently cover the slopes from top to bottom. The terracing has slowed down the process of erosion and has made it possible to cultivate additional areas by using the steeper slopes—some of which have grades up to 45° or more.

THE SOUTHEASTERN MOUNTAINS

Southeastern China is bordered by a rocky shoreline backed by picturesque mountains. In general, there is a distinct structural and topographic trend from northeast to southwest. The higher peaks may reach elevations of some 5,000 to 6,500 feet (1,500 to 2,000 m). The rivers are short and fast-flowing and have cut steep-sided valleys. The chief areas of settlement are on narrow strips of coastal plain where rice is produced. Along the coast there are numerous islands, where the fishing industry is well developed.

PLAINS OF THE MIDDLE AND LOWER YANGTZE

East of Yichang, in Hubei province, a series of plains of uneven width are found along the Yangtze River (Chang Jiang). The plains are particularly wide in the delta area and in places where the Yangtze receives its major tributaries—including large areas of lowlands around Dongting, Poyang, Tai, and Hongze lakes, which are all hydrologically linked with the Yangtze. The region is an alluvial plain, the accumulation of sediment laid down by the rivers throughout long ages. There are a few isolated hills, but in general the land is level, lying mostly below 160 feet (50 m). Rivers, canals, and lakes form a dense network of waterways. The surface of the plain has been converted into a system of flat terraces, which descend in steps along the slopes of the valleys.

THE NAN MOUNTAINS

The Nan Mountains (Nan Ling) are composed of many ranges of mountains running from northeast to southwest. These ranges form the watershed between the Yangtze to the north and the Pearl (Zhu) River to the south. The main peaks along the watershed are above 5,000 feet (1,500 m), and some are more than 6,500 feet (2,000 m). But a large part of the land to the south of the Nan Mountains is also hilly; flatland does not exceed 10 percent of the total area. The Pearl River Delta is the only extensive plain in this region and is also the richest part of South China. The coastline is rugged and irregular, and there are many promontories and protected bays, including those of Hong Kong and Macau. The principal river is the Xi River, which rises in the highlands of eastern Yunnan and southern Guizhou.

THE SOUTHWESTERN REGION

The southwest is a cold, lofty, and mountainous region containing intermontane plateaus and inland lakes. It can be subdivided into two second-order geographic divisions.

THE YUNNAN-GUIZHOU PLATEAU

The Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau region comprises the northern part of Yunnan and the western part of Guizhou; its edge is highly dissected. Yunnan is more distinctly a plateau and contains larger areas of rolling uplands than Guizhou, but both parts are distinguished by canyonlike valleys and precipitous mountains. The highest elevations lie in the west, where Mount Diancang (also called Cang Shan) rises to 13,524 feet (4,122 m). In the valley...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Geographic Overview

- Chapter 2: Human Interactions with China’s Environment

- Chapter 3: Major Chinese Physical Features

- Chapter 4: Spotlight on China’s World Heritage Sites and Other Notable Locations

- Chapter 5: Beijing

- Chapter 6: The Major Cities of Northern China

- Chapter 7: The Three Great Cities of Southeastern China

- Chapter 8: Other Major Cities of Southeastern China

- Chapter 9: The Major Cities of Southern and Western China

- Chapter 10: Special Administrative Regions

- Chapter 11: Selected Autonomous Regions

- Chapter 12: Selected Provinces

- Appendix: Statistical Summary

- Glossary

- For Further Reading

- Index