This is a test

- 300 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Dickens and Popular Entertainment

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First published in 1985. Dickens was a vigorous champion of the right of all men and women to carefree amusements and dedicated himself to the creation of imaginative pleasure. This book represents the first extended study of this vital aspect of Dickens' life and work, exploring how he channelled his love of entertainment into his artistry. This study offers a challenging reassessment of Nicholas Nickleby, The Old Curiosity Shop and Hard Times. It shows the importance of entertainment to Dickens' journalism and presents an illuminating perspective on the public readings which dominated the last twelve years of his life. This book will be of interest to students of literature.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Dickens and Popular Entertainment by Paul Schlicke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literatur & Britisches Drama. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Dickens and the Changing Patterns of Popular Entertainment

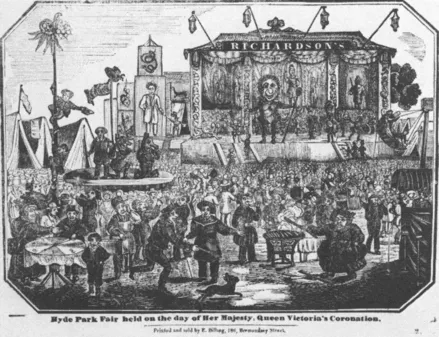

The fair in Hyde Park - which covered some fifty acres of ground - swarmed with an eager, busy crowd from morning until night. There were booths of all kinds and sizes, from Richardson's Theatre, which is always the largest, to the canvas residences of the giants, which are always the smallest; and exhibitions of all sorts, from tragedy to tumbling ...

This part of the amusements of the people, on the occasion of the Coronation, is particularly worthy of notice, not only as being a very pleasant and agreeable scene, but as affording a strong and additional proof, if proof were necessary, that the many are at least as capable of decent enjoyment as the few. There were no thimble-rig men, who are plentiful at racecourses, as at Epsom, where only gold can be staked; no gambling tents, roulette tables, hazard booths, or dice shops. There was beer drinking, no doubt, such beer drinking as Hogarth has embodied in his happy, hearty picture, and there were faces as jovial as ever he could paint. These may be, and are, sore sights to the bleared eyes of bigotry and gloom, but to all right-thinking men who possess any sympathy with, or regard for, those whom fortune has placed beneath them, they will afford long and lasting ground of pleasurable recollection - first, that they should have occurred at all; and, secondly, that by their whole progress and result, at a time of general holiday and universal excitement, they should have yielded so unanswerable a refutation of the crude and narrow statements of those who, deducing their facts from the proceedings of the very worst members of society, let loose on the very worst opportunities, and under the most disadvantageous circumstances, would apply their inferences to the whole mass of the people.1

On 28 June 1838, England celebrated the coronation of its young

Dickens visited the Coronation Fair held on 28 June 1838 and found it 'particularly worthy of notice' as proof that 'the many are at least as capable of decent enjoyment as the few'.

queen, but not all eyes were on the pomp of the official ceremonies. Her Majesty's most famous novelist, breaking off a characteristically energetic holiday in Twickenham and interrupting work on two, novels in progress (he was writing both Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby at the time, as well as editing Bentley's Miscellany), went instead to Hyde Park to witness the festivities of the common people. His brief account of the great fair, which lasted for nine days and 'attracted all the great exhibitions in the country with a whole army of minor showmen', appeared as the tail piece to an article on the coronation in the Examiner.2 Although what Dickens wrote consists of no more than a few lines of unsigned journalism, the lines which I have quoted above reveal plainly the fervour of his convictions about popular entertainment. His delight in the fair is abundantly clear, and he is stout in his support of the ordinary men and women who participate in the national occasion. He writes as a fascinated observer, with a ready eye for absurdity (the residences of the giants are 'the smallest') and an obvious familiarity with his subject (the residences of the giants are 'always the smallest'). He recognizes the vulgarity of the scene but compares it favourably to more 'respectable' amusements and invokes the tradition of hearty English enjoyment, as recorded by Hogarth, as evidence of its time-honoured value. It is also apparent that he feels a distinct need to come to the defence of these popular celebrations. His attacks on the 'bleared eyes of bigotry and gloom' and his appeal to 'all right-thinking men' indicate the contentious nature of his subject and signal his readiness to enter the fray. In the early days of his career, at the very outset of the Victorian era, the amusements of the people were under attack from many directions, and Dickens, the great popular entertainer, was their champion.

His love of entertainment dated from childhood, and it was a lifelong commitment. From his schoolboy production of The Miller and His Men in a toy theatre, through the novels, amateur theatricals and public readings of his adulthood, Dickens devoted himself to providing entertainment for others. His friend and biographer John Forster noted a 'native capacity for humorous enjoyment' as one of his distinctive characteristics, and the eagerness with which he sought amusement is attested by the restless curiosity with which he wandered the streets of London, the avid frequency of his theatre-going, the urgent appeals to friends to join him in some new delight. His daughter Mamie wrote that, despite the delicacy and illness which afflicted Dickens as a youth, in his manhood sports were a 'passion' with him; he participated in bar-leaping, bowling and quoits, enjoyed cricket 'intensely' as a spectator, and organized field sports for local villagers in a meadow at the back of Gad's Hill Place.3 The forms of entertainment which he enjoyed most were essentially popular. He responded with unashamed pleasure to the circus and the pantomime, to sensational melodrama and the Punch and Judy show. Such entertainment, as distinct from élitist culture which demanded education, wealth and social position, was broad-based in its appeal, inexpensive and widely available.4 As a journalist he watched it observantly; as a social reformer he applauded its benefits for the people; as a popular artist he shared its aims; and as a participant he wholeheartedly entered into the fun.

Entertainment was a subject Dickens wrote about often and, as we shall see in chapters which follow, it assumes central structural and thematic importance in three of his novels. More fundamentally, entertainment is linked inextricably with the nature of his art. His earliest fiction began in conscious imitation of popular literature of the day, and Pickwick became the publishing sensation of the nineteenth century. He was the most widely popular English writer since Shakespeare, and even as his artistry matured in depth and complexity he never abandoned the basic intention of providing his audience with amusement. His repeated advice to fellow-novelists was to take seriously the need to entertain readers; the avowed intention of his journalism was to transcend 'grim realities' by showing that 'in all familiar things. . . there is Romance enough, if we will find it out'. This declaration, like the command to his subeditor W. H. Wills 'KEEP HOUSEHOLD WORDS IMAGINATIVE!' - stressed the appeal to man's innate sense of wonder and curiosity which it is the entertainer's purpose to arouse.5 He made this appeal most directly when, in the final twelve years of his life, he turned largely away from fiction and journalism to appear in public as a reader of his work. Central to his role as an artist, integral with his social convictions, rooted in his deepest values, and a source of lifelong delight, popular entertainment reaches to the core of Dickens's life and work.

During the formative early years of his life, English popular entertainment was in a process of radical transformation. The old rural pastimes of the people, which had been benignly tolerated by the gentry as integral to a social stability based on traditional life-styles, were increasingly eroded, and by the 1830s very little had emerged to take their place. The great urban fairs, having long since lost their commercial function, were susceptible to determined efforts to suppress them, and the greatest of them, Bartholomew Fair, was effectively put down by civic fiat in 1840. Rapid urbanization and population explosion eliminated open spaces which had formerly been used for leisure activities and gave the public house vital importance as a social centre. The rise of the factory system introduced a fundamental change in the conception of work, away from the variety of seasonal occupation to a regimented, mechanical system, even as the vast pool of cheap labour ensured that men, rather than machines, performed most of the tasks that were done. The hours and conditions of work were a source of seething discontent among the labouring poor, particularly in the industrial North, and legislative proposals for dealing with labour problems were put before Parliament year after year. There were a few gains: violent sports such as bull-baiting and cock-throwing had virtually dis-appeared by the 1820s, and the rise of railways in the 1830s made it increasingly possible for people to travel to permanent exhibitions and resort areas. Metropolitan exhibition-halls and minor theatres flourished, but not until after mid-century did music-halls, organized sports, public recreation facilities, Saturday half-holidays, and other possibilities for urban amusement arise. Most modern historians are convinced that the nadir of English popular culture was reached during the 1830s, the very time Dickens began writing about it.6

The decline of older forms of popular entertainment was only one aspect of the alteration of English society, which was entering a particularly dynamic phase in the 1830s. During these years England changed from a rural, agrarian-based economy to an urban, industrialized state, a shift most dramatically symbolized by the railway boom. Between the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in 1830 and the time Dickens was writing The Old Curiosity Shop in 1840, nearly 1,500 miles of track had been built in the United Kingdom and over 2,500 miles sanctioned, unavoidable evidence of the speed, power, size and disruption the new heavy industries were bringing.7 Commerce and industry became heavily capitalized as never before; parliamentary life was altered by the Reform Act of 1832, and there was a host of new social legislation, most notably the Factory Act of 1833 and the New Poor Law of 1834. Ferment in religion (the Oxford Movement), in politics (Chartism), in economics (Mill's Essays, not published until 1844, were written around 1830), in social philosophy and history (Carlyle wrote Sartor Resartus, The French Revolution and Chartism in this decade) indicates only some of the pressures during this era. By the time Victoria came to the throne in 1837, a revaluation of manners, morals, thought and feeling was in full flood.

Popular amusements were inevitably caught up in the general movement of change. In the long term, there was a decisive shift away from gregarious, participatory activities towards large-scale spectator entertainments such as music-hall and professional sport. The most striking instance of this trend, which historians have referred to as the 'commercialisation ofleisure', is the circus.8 Philip Astley opened his circus at Westminster Bridge in 1769 with a modest show of horsemanship exercises, and during the nineteenth century his enterprise grew phenomenally in scope and grandeur, culminating late in the century under 'Lord' George Sanger's direction with extravaganzas such as Gulliver's Travels, which Sanger himself in all modesty described as

... the biggest thing ever attempted by any theatrical or circus manager before or since. In the big scene there were on the stage at the time three hundred girls, two hundred men, two hundred children, thirteen elephants, nine camels, and fifty-two horses, in addition to ostriches, emus, pelicans, deer of all kinds, kangaroos, Indian buffaloes, Brahmin bulls, and, to crown the picture, two living lions led by the collar and chain into the centre of the group.9

Jerry's dogs in The Old Curiosity Shop pale rather, in comparison. Sanger himself provides the archetypal example of the commercialization of entertainment, graduating from a boy's exhibition of six white mice to his later orchestration of massive productions like the one described above. Inspired by Astley's, other circuses sprang up, consisting initially of little more than a few routines on horseback. The shows gradually became more elaborate and various, but wild beast acts were included only from the late 1830s and elaborate feats of daring after mid-century. A few modest circuses soldiered on until the end of the century, but the trend, in circus, in music-hall and in sport, was towards size and expense, culminating in the birth of the mass-entertainment industry in the early years of the twentieth century.

Transition, then, was the keynote during Dickens's lifetime. His writing registers the decline of old patterns and the difficulty of establishing new ones. He is concerned with the replacement of traditional kinds of leisure activities by new forms and, more centrally, with changing attitudes to entertainment. He is staunch in his resistance to pressures antagonistic to amusement, but he is also warmly supportive of forces for improvement. For example, he was an intimate adviser at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, during its management by his friend William Charles Macready, who endeavoured to improve the environment of the theatre by banishing prostitutes from it, and to raise the level of performance by insisting on proper rehearsals. Dickens's association with Macready's celebrated 1838 production of King Lear had direct consequences for his fiction.10 He published articles in his journals circumstantially praising Madame Tussaud's waxwork museum for having become a 'national institution'; others noticing the worthy efforts of musical clubs to provide 'an emollient for brutal tastes', extolling the benefits of opening Kew Gardens and the British Museum to the public, comparing the licentiousness and riot of ancient May Days with the exhilarating May Day 1851, when British industry made possible a structure more wonderful than the palace Aladdin raised with his lamp, the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park.11 Above all, his own career gives clear evidence of his positive response to trends of the day: he kept scrupulous watch on the financial value and audience appeal of his writings, and his decision to embark on the public readings which dominated his last years, under the management of a professional theatrical agency, represented a fulfilment of his earliest aspirations within the context of the emerging commercial circumstances.

But the fundamental point about Dickens's attitudes to popular entertainment, the fact which deeply colours his relationship to it, is that his attachment is rooted in the traditions of the past. There are two principal reasons why this is so. First, the values which he associates with entertainment have less to do with its increasing scale and commercialism than with the old communal patterns. For Dickens, entertainment was a locus for the spontaneity, selflessness and fellow-feeling which lay at the heart of his moral convictions. The human enjoyment by family and friends of shared amusements had meaning for him far above the aesthetic accomplishment of the professional entertainer impersonally exhibiting his skills before an anonymous audience. He was well aware of the vast difference in quality between entertainments, and both in his own work and in his response to that of others he strove determinedly for excellence. Nevertheless, it is abundantly clear from the evidence of his life and work that he found ample cause for delight in simple, lowly or even absurd entertainments; whether he laughed with or at the showmen, what mattered was that they provided amusement. In his writing he focused largely on the humble aspirations of individual showmen, earning their honest penny by bringing colour, novelty and amusement into people's lives; on the fraternal feelings of entertainment troupes, giving pleasure to themselves as they offered it to others; and especially on the needs of the solitary individual, struggling to alleviate the burdens of his or her life in imaginative release. Even when he deals with commercial entertainment, such as Crummles's strollers or Sleary's equestrians, Dickens concentrates less on the economic basis of their enterprises than on the feelings which motivate their work; he happily records the gusto and dedication with which they perform, he takes us offstage to glimpse the quality of their lives, and he singles out knots of spectators eager for gregarious pleasure. As a writer he cultivated a strong sense of personal relationship with his readers, and his public readings were motivated not only by the attraction of financial gain but also by the opportunity they provided for an even closer intimacy with his audience. His emphasis lay on par...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Preface

- List of Illustrations

- References and Abbreviations

- CHAPTER 1 Introduction: Dickens and the Changing Patterns of Popular Entertainment

- CHAPTER 2 Popular Entertainment and Childhood

- CHAPTER 3 Nicholas Nickleby The Novel as Popular Entertainment

- CHAPTER 4 The Old Curiosity Shop The Assessment of Popular Entertainment

- CHAPTER 5 Hard Times The Necessity of Popular Entertainment

- CHAPTER 6 Popular Entertainment in Dickens's Journalism

- CHAPTER 7 Dickens's Public Readings: the Abiding Commitment

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Index