![]()

1

Problems of Adolescence

A. HYATT WILLIAMS

Classification is difficult because there are several scales, ranges or dimensions present in each individual. The adolescent is growing up in at least one, and usually several, social groupings. He brings to the multitudinous problems which are centred round puberty the psychosocial problems derived from the other social groupings which complicate the issue of adolescent development. Each action carried out in the present is based upon the past and materially influences the future.

Looking with hindsight as the history unfolds, one can discern the way in which sequences of events could have been forecast without any special ability or omniscience. With experience, how often it appears that such predictions can be made in advance. There is always the unexpected, however, which arises from within the individual, or externally from one social grouping or another. Sometimes it occurs in the wider environmental field and vitally influences the adolescent. An example of the first is when some sudden internal psychic shift takes place and the once-diligent prepubertal pupil becomes the ‘drop-out’ student of the next decade. An example of the second cause is the fatal illness and death of a member of the nuclear family. An example of the third is a catastrophe such as an air-crash, flood, motor accident or even a crime of violence which impinges upon the individual at risk in so massive a way that emotional digestion and metabolism cannot keep pace with the overwhelming stress of the moment.

The child at the end of the latency period is relatively well adapted to his environment. He has become skilled in a whole variety of ways. For example, as a pedestrian in both rural and urban settings he has become remarkably safe and reliable. Formal knowledge is being acquired and a lot of it integrated at a fairly fast rate, although such initiation tests as the eleven-plus sometimes put the latency child into considerable disarray. The prescribed position in which the adolescent finds himself within the family group has usually reached some degree of stability by the end of the latency period. Then with varying degrees of suddenness, puberty with its biological changes breaks and all the secondary turmoil which constitutes the adolescent process follows sequentially in an infinitely variable way. Beneath all this variable super-structure, which at times is confusing to the adolescent himself, and also to the people who have to deal with him, is a substructure of invariability. How do we study the interaction between the variables and the invariables?

Adolescence is the period of experiencing and resolving the turbulence which is set into action by the biological process of puberty. Change in size and status within the home and in the wider environment are not the least of these. Adolescence ends with the beginning of adult life. Adolescence therefore is the consequence of puberty and the extent to which it taxes the adaptive capacities of the young person varies from culture to culture and also depends to some extent upon the biological acuteness of the onset of puberty. The first way of looking at adolescent problems therefore is to see how the individual is put under stress and how his adaptive capacities are able to cope with the various challenges. Sometimes the main difficulties are experienced as being situated at home within the nuclear family, sometimes at school, college, university or place of work, and sometimes elsewhere. Any interactive situation is liable to be designated as the cause of the difficulty, so that the real stress situation may not become clearly discernible until preliminary sorting out has been undertaken. It may well be that some of the sorting out can be conducted by non-medical agencies and this is the value of the counselling services for young people. As in childhood where the help of parents is sought and instant remedies often found possible, so the adolescent seeks for help from authorities including parents, schoolteachers and others. Rarely are such instant remedies and solutions to problems—such as those effective in the former childhood difficulties—possible in the case of adolescent problems. The young person at this juncture often becomes disillusioned and angry with the helping authority, blames it for not helping more, and designates it as being punitive and useless. This is one of the common causes of the alienation of adolescents from even helpful and benign authority and the inevitable drift is towards a peer group for mutual comfort and understanding. Sometimes the peer group is sought for more disturbed and destructive activities such as revenge upon authority or the easy options of drink, drug-taking, etc. Sometimes the peer group is only minimally alienated from society at large and may, in certain respects, be a good deal more constructive and far-sighted than the society against which it is in rebellion. Again there is a spectrum or scale. At the severely disturbed and alienated end there is delinquency, drug-taking and behaviour which seems to be orientated more towards death than life.

So far we have been considering adaptation and the stresses to which the adaptive capacities of the adolescent are subjected. No mention has been made of psychological illness. A point may be reached, however, beyond which, if stresses continue or are increased, adaptive capacities are overwhelmed.

The problem is very confused and complicated because the overwhelming of the adaptive capacities may result in a definitive illness on the one hand or there may be a character distortion, for example in the direction of delinquency, or there may be a reduction in achievement. Most often, however, there are mixtures of these three and also there are other kinds of response. For example, one fifteen-year-old boy responded to the desertion of the family by his beloved father by poor scholastic performance, by fire-setting and also by turning to very destructive, aggressive and sexual behaviour towards young children of either sex, including his own siblings. He was not a talker but a doer. Eventually, when it was possible to get him to speak he gave as his reason for the behaviour, which utterly disregarded the rights and satisfactory development of a young girl, that he did not care what the effect upon her was although he did not dislike her. When asked to explain why this was so, he said immediately and with much feeling, ‘My father did not think of the effect on me of his leaving home and my never seeing him.’

Adolescent disturbances and breakdown patterns are similar to those of adults in that they take place along the lines of personality cleavage which were laid down during the earlier phases of emotional development. The fixation points referred to in Adolescence, Chapter 1, constitute the weaknesses or cleavage lines which are especially vulnerable to later stress situations. These situations may consist of what is going on in the inner world, that is intraphysically, or in the outer world, that is psychosocially. Or they may be due to disturbances of the body image due to illness or other damage to the body including delusions about the body. What is different about the disturbances of adolescents from those of adults is the instability of the whole situation. Nothing is fixed and all feelings are powerfully represented so that turbulence is maximal. Also there can be rapid shifts from a wise and seemingly adult intellectual understanding to a rage or panic-driven state like that of a young child in a wild tantrum.

Particularly characteristic of disturbed adolescents is the way in which individual distress tends to be expressed in group relationships based upon the extemalisation of blame and responsibility. In this case the goodness is usually ascribed to the adolescent in-group and the badness to the adult world outside. Particularly singled out for hostility, of course, is the police force. In general, adolescent disturbance consists of too much yielding to instincts, acting-out, delinquency, promiscuity, etc. But also there can be too much inhibition of instincts, inactivity, indolence, inability to hold a job, inability to study and the restrictive neurotic disturbances. If the ego structure is too flimsy the adolescent personality seems unable to contain the powerful forces which reside within it. On the other hand, too harsh a superego or persecuting conscience leads not only to inhibition but may lead to a great increase of internal tension and subsequently a major outbreak in the form perhaps of antisocial behaviour or of suicide or suicidal attempt. Much depends upon the identifications. In general, the adolescent may be a conformist and identify with the authority in which case he is likely to be prudish, perhaps arrogant, smug, complacent and in general ‘holier than thou’. On the other hand he may identify with the underdog and the authority becomes designated as the enemy to be torn down however good it is. A third way of dealing with problems is to form part of a delinquent subculture. Sometimes the delinquency constitutes a subculture within the personality of the individual so that at home, at school, at university or even at work, he is a perfect conformist and gives no trouble but at the same time within his peer group leads a secret delinquent life. The recent escalation of drug taking facilitates this kind of split.

One of the greatest difficulties with which the adolescent may have to cope is when the authority figures, parents especially, are corrupt. This means that when, by introjection, projection and reintrojection occurring repeatedly in the formation of the superego, criminal corrupt authorities form important ingredients or constituents of the conscience of the individual. Of course, this kind of happening takes place much earlier in life than adolescence and is important long before puberty is reached. But it is during the adolescent phase that it assumes new importance. This is partly because of the increased stresses acting upon the adolescent and partly because of his greater impact upon his social and cultural environment. He is more mobile and delinquent action is likely to have wider repercussions. The condition of having superego figures who are corrupt is serious because in circumstances in which ordinary people can obtain help and guidance from their moral but not too punitive superegos, corrupt superego figures are unreliable, capricious, sometimes allowing delinquencies and sometimes forbidding arbitrarily non-delinquent behaviour. At worst, there is a sneering at the good side of the adolescent, and the encouragement or the acquiescence over the delinquent side. Sometimes a hostile parent deliberately corrupts or an envious relative encourages the destructive and brutalised aspects of the young person. An example from literature is the way in which Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights corrupted the young Eamshaw, and another example of the opposite kind is in Treasure Island where Long John Silver made no serious attempt to corrupt Jim Hawkins.

Seduction during childhood can influence maladjustment at adolescence. Freud made reference to the seduction in childhood of both a real and a fantasy nature and concluded that although actual seduction was common, a great deal was contributed by the fantasies of the child. Nevertheless, seductions do take place and these can be seen to fall roughly into the categories of threats to life and threats to the integrity of the body. The other kind of traumatic event is the seduction which is frightening but stimulating. Whether seduction occurs with excitement and cruelty or whether it occurs with excitement and kindness, the result seems to be little different. The excitement and cruelty seems to trigger off a tendency in the person who was seduced as a child to do actively to other people representing himself as he then was what he or she experienced passively in childhood. Excitement linked with kindness tends to perpetuate the distortion involved in the original seductive relationship; for example, to perpetuate a homosexual object choice or various sexually perverse practices. Whichever way we look upon the problem, it is certainly true to say that the basic pattern of behaviour, of personality development and of attitude to life, is laid down early on in personal development. It would be fair to say that constitution and heredity are basic but that the actual events of life and actual experiences also contribute a great deal. An example of the effects of trauma during a state of persecutory anxiety would be a relatively minor seduction which is experienced by the individual child as an extraordinary, malevolent, cruel and destructive event leaving an indelible effect upon him and causing him to live from then on with a sense of grievance and to feel that, having been wronged, he is quite entitled to perpetuate wrongs wherever he goes for the rest of his life.

In trying to understand the perplexing morass of adolescent turbulence it is important to look for guide lines. Some of these were described in Adolescence, Chapter 1. They will be recapitulated briefly and slightly differently here. According to the theories of Klein and her co-workers, the emotional development of the infant was stated to proceed from a phase dominated by persecutory anxiety which consists of a fear of attack, even to the point of annihilation, by malevolent agencies, experienced at this phase as part-objects. This means that the infant experiences a persecutory breast, not a bad mother. The depressive position is described by Klein as that phase which is initiated by the recognition by the baby of the mother as a person, rather than as a collection of parts. The hostile feelings which the baby had experienced and expressed towards the bad breast (a part-object) and the loving and grateful feelings felt towards the good gratifying breast (still part-object) come together in relationship to a whole mother, with both kinds of attributes. Depressive anxiety arises due to concern for the good object and of fear lest the hostile destructive feelings should be more powerful than the loving ones. On that account, there is a risk that the whole mother will be driven away or destroyed. This experience constitutes a change and a development. Depressive anxiety involves feelings of concern and responsibility. Persecutory anxiety involves only feelings of fear and aggrievedness. If the depressive position is worked through to some extent in infancy, the baby is able to extend and deepen its relationships. These relationships are first with its mother, experienced as a whole person, and then with father and then with other people. Normally there is some negotiation of the depressive position and it may be some time before an inadequate negotiation of the depressive position is recognised. The signs of this will be shown in various intrapsychic and psychosocial difficulties in the course of the development of the young child. In all people, however, there are constant relapses into states dominated by persecutory anxiety, however well the depressive position has been negotiated in infancy. At the end of the scale which is dominated by depressive anxiety, there can be growth, development and a capacity for the unconscious adaptive process known as sublimation. People, represented intrapsychically by images (often called internal objects in this book) are tolerated and there is an on-going relationship with them. The intrapsychic or inner world of the individual and the interpersonal or social world with other people can be kept in some sort of working relationship and for short periods of time even in harmony. In favourable states which are dominated by depressive anxiety, a good deal of unconscious psychic work is done. This means that the inner world of fantasy of the individual is used as a valuable testing-out ground, and valuable steps in integration and maturation. Violent turning away from the breast, from the mother, and from all other persons who are felt to be frustrating is characteristic of the paranoid/schizoid phase of emotional development. This is the phase which is dominated by persecutory anxiety. The persecutory response to the deprivation of weaning is characterised by a violent turning away from the breast or bottle. It usually lays down a pattern of behaviour which is repeated on every occasion in life where there is a loss or separation from either good objects or those gratifications which are felt to be necessary by the individual. I feel that the influence of early infancy on later maladjustment cannot be overstated:

- The kind of turning away from the breast or bottle is likely to be typical of later responses to frustration or deprivation.

- The more violent the turning away from the primal object, i.e. breast-bottle and later mother, the more unlikely it is that there was much success in reaching and working through the depressive position, and individuals of this kind tend to express their difficulties and distress in deeds rather than being able to do the work within their minds until the situation has, to some extent, been improved.

- It is the latter category of people from whom mal-adjusted individuals, criminals and delinquents are largely recruited.

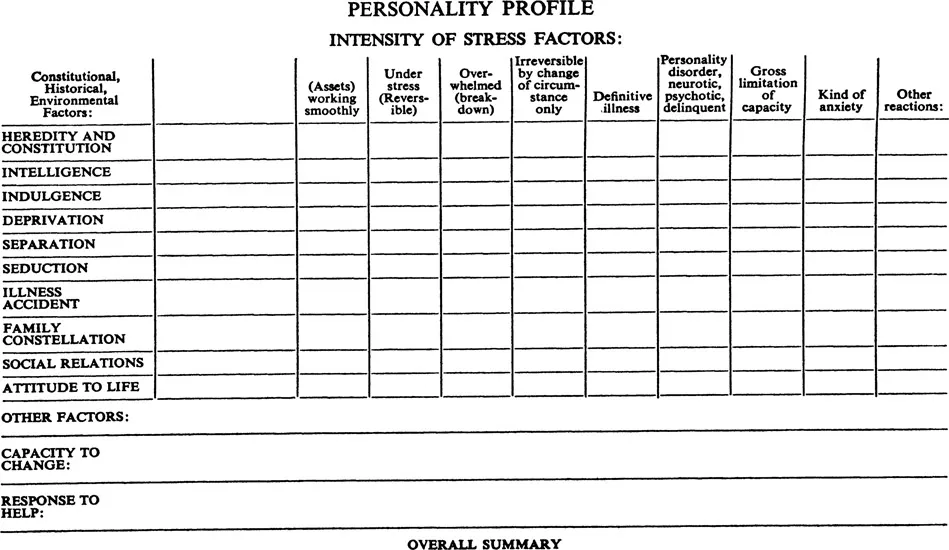

A Way of Assessing Adolescent Problems: The Personality Profile

As has been stated already, breakdowns and illnesses which occur during the period of adolescence are difficult to classify as they are due to an interplay of factors and usually, therefore, cannot be regarded as disease entities. Possibly a more useful way of assessing the adolescent who is referred for one reason or another to the health or the other caring services would be to look at the disturbance in the setting of the total personality of the individual, and then to consider the individual in his various social settings, beginning with the nuclear family and continuing with the school, university or work setting, etc. In this way a personality profile can be looked at and the areas of disability evaluated. There can be a classification without loss of the overall integrative picture of the whole individual.

With the aim of facilitating the study of the disturbed adolescent who has been referred or who has brought himself or herself for help of one kind or another, a diagrammatic chart or grid has been drawn out. The one which is given at the end of this chapter is crude, may not be suitable, and certainly needs modification by individual workers who are attempting to look at adolescent persons who have to be seen in a meaningful way. The principles involved in such a scheme are simple. The aim is to present graphically the kinds of disturbance, the areas and phases of development from whence they stem, their significance in the total picture of the personality of the individual involved, their intensity, and their relationship to the contemporary functioning of the individual. In addition it will be quite clear when the schema is looked at that it will not be filled in completely for every

adolescent referral. The schema acts as an aide-mémoire so that important areas of the personality are not neglected and can be run over by the worker so that no major factor is omitted.

The vertical categories deal with heredity and environmental factors and then go on to later impositions such as separation, illness and various traumatic happenings. The horizontal column denotes mainly intensity and the way in which the various stress factors have been dealt with or woven into distortions and disabilities of character. I would suggest that a five-point index of quantity or intensity be used, either 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 or A, B, C, D, E, but there is no reason why a descriptive word or phrase should not be put in any given box. There are spaces for the inclusion of special individual factors. Finally there is space at the end for short summaries involving a sentence or two. It must be stressed that the schema has nothing particularly magical about it and it should be modified, cast aside or totally replaced by something which works bètter for the individual who wishes to use this kind of schema. If we try to use the grid for one or two actual patients, the point of it might become clearer.

P.L. was a sixteen-year-old, well-built boy from a tropical country, whose parents referred him in collaboration with the school where he was a boarder, on account of his academic failure and apparent boredom. The scale will show how the trouble can be located in the area of intellectual capacity and traced to birth trauma consisting of rather prolonged anoxia. The mother was asked about the birth of her son, who was her eldest child, and stated that she had been in labour for three days and then had to have an emergency Caesarean operation. The doctors at the time were concerned about the prolonged anoxia and thought it must have a profoundly deleterious effect upon the intelligence and future development of the baby. The other children in that particular family were all of very high intelligence. The boredom of P.L. was explained as a withdrawal, partly defensive, against very primitive anxieties and partly becaus...