![]() PART 1

PART 1

Film, Video and Multimedia![]()

1

Trevor Jones’s Score for In the Name of the Father

David Cooper

I’ve done a handful of films in my time that I feel are particularly significant. These are films that have commented on, and I believe contributed to, changing people’s perception or understanding of particular subjects. One such film was In The Name of the Father, which, I believe, was screened for the House of Commons and the House of Lords. I feel that this did change the British government’s attitude and their policies at that time with regard to the Irish question. Up to that point we were interviewing Sinn Féin people behind frosted glass and using actors’ voices. I wanted to score this film because I felt I could contribute, in however a small way, to such an important issue. Other such films include Alan Parker’s Mississippi Burning, which looked at the question of racial tension in 1960s America, and Aegis, the Japanese film which raised the question of the North Korean threat to Japan.1

This chapter considers how the various sources, both textual and auditory, can offer insight into the technical processes and musical judgements which go into the creation of a film’s score. It also examines how film may use the meanings encoded in music to support the unfolding of the narrative. It is suggested that Jones’s approach in his score for the film In the Name of the Father, directed by Jim Sheridan, which incorporates songs performed by Bono, Sinéad O’Connor and others, offers an interesting model of an integrated soundtrack employing composite sources in which the composer has moulded and influenced the popular.

Born in Cape Town, South Africa, in 1949, Trevor Jones has an extensive filmography that includes popular mainstream cinema for both Hollywood and independent studios, and work for television. As a postgraduate student at the University of York, his teachers included Wilfrid Mellers (1914–2008) and Elisabeth Lutyens (1906–83), and both of these were influential on his philosophy and approach to film-scoring. Mellers, a man of broad musical tastes that spanned artmusic, jazz and popular music, had established the York Music Department in 1964, and fashioned there a very liberal curriculum and a pedagogical approach that integrated analysis, performance and composition.2 As well as being one of Britain’s most successful women composers, Lutyens had a successful career writing for film with more than 20 pictures to her name. Her modernist language had found a particular home in the British horror genre, and she was able to communicate with Jones both as a serious art-music composer and someone familiar with the professional practice of film production. In her autobiography, Lutyens would remark of media composition that:

Both films and radio music must be written not only quickly but with the presumption that it will only be heard once. Its impact must be immediate. One does not grow gradually to love or understand a film score like a string quartet.3

While it could be argued that changes in technology since the time of Lutyens’ comments have transformed the relationship between film and its audience, and it has become increasingly feasible with media such as video and DVD to develop a fuller understanding of a film score and its relationship to the rest of the film’s narrative elements over time, the importance of immediacy of film music’s impact remains.

Jones completed his studies at York in 1977, and from 1979 his name began to appear in credits as composer or member of the music department for film releases. John Boorman’s Excalibur (1981), which also drew on the music of Richard Wagner and Carl Orff, was an early success for the composer and in the subsequent two decades he became established as a figure who was both versatile and technically sophisticated, scoring a large number of mainstream films. His career has spanned the move from analogue to digital technology, and he is a representative of a generation of composers who are also very competent music technologists, at home with both the symphony orchestra and the electronic studio. At the time of writing, Jones has a list of more than 80 films and has worked for directors such as Jim Henson, Andrei Konchalovsky, Alan Parker, Michael Mann and Ridley Scott.

The Trevor Jones Archive of film music recordings was donated by the composer to the School of Music at the University of Leeds in June 2005. The archive consists of around 400 two-inch reels of 24-track analogue audio and associated paperwork including spotting notes, cue sheets and information about multitrack recording, mixing and effects. It embraces the analogue tapes of the scoring sessions from Jones’s student work at the National Film School through television and advertising work to major movies such as The Dark Crystal (1982), Runaway Train (1985), Labyrinth (1986), Angel Heart (1987), Mississippi Burning (1988), Sea of Love (1989), Arachnophobia (1990), Freejack (1992), Cliffhanger (1993), Richard III (1995), and Brassed Off (1996).4 Jones has also supplied more recent material created and stored digitally.

Session recordings and related documentation offer a rich resource that contains important evidence about the development of the film score. The multitrack recordings include both synthesized mock-ups and final mixes and provide data about balance, orchestration and synchronization, as well as the structure of recording sessions and deliberations made during mixing of the score. While the study of multiple recordings of a single cue can help to identify subtleties in the development of the score, and the examination of recordings of a sequence of cues can shed new light on the development and progression of the scoring process, these materials may also enable greater comprehension of a composer’s overarching musical scheme for a film. Once recording and mixing are completed, the fate of a film score usually leaves the control of the composer, and decisions taken by the director on the dubbing stage can lead to a composer’s carefully crafted musical structures being radically transformed. However, evidence for the putative larger-scale musical organization of a film score can be found in the various session recordings and notated score for a film. Consideration of the composer’s apparent intentions and the influence of other members of the production team as documented in paperwork, such as spotting notes and track sheets, can enable scholars to more precisely contextualize the ‘final’ soundtrack (in as much as it is ever final) in terms of its importance in defining ‘the film score’.

Documentation held in the University of Leeds archive varies from film to film, but includes:

• spotting notes

• ‘sync pop’ placements

• scoring log revisions

• multitrack sheets.

In addition, Jones has given researchers at the University of Leeds access to copies of short and full scores in order to reproduce them photographically. To illustrate the range and content of the archive, some of the materials associated with Jones’s score for Geoff Murphy’s Freejack (1992) are discussed below.

Freejack Musical Documentation

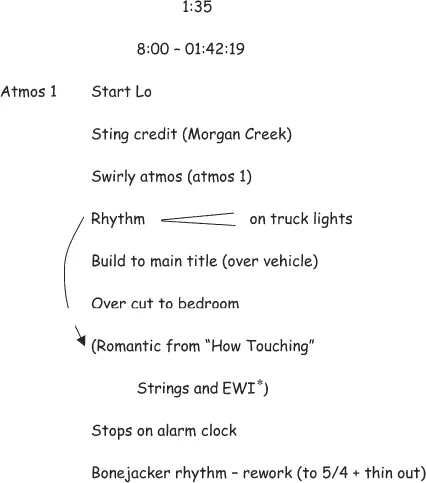

Music Spotting Notes of 11/10/91 (US Date Format)

Spotting notes derive from the post-production discussions held between the composer and senior figures involved with the production (generally the director). They indicate the position and length of scenes within a reel of film for which music is to be provided, as well as contextual information (for example, a description of the action or the kind of music expected) and are differentiated by a series of cue number codes. The numbering system generally adopted for cues indicates: first, the reel of film; second, the fact that it is a music cue; and, third, the cue number within the reel. Some cues also terminate with the letter ‘S’ to indicate a ‘source’ cue – in other words, one involving existing, rather than specially written, music.

The spotting notes for Freejack consist of 17 typescript pages numbered from 1 to 18, the fourth page being missing. It appears from the content of the remaining pages that page 4 was probably blank and separated the first three pages (which are titled ‘underscore’ and contain a list of cue numbers, titles, durations and very brief narrative descriptions) from the final 14 pages which have one or two pages of information per reel and include detailed typed notes about the narrative and the potential musical content. The first and fifth pages have the note ‘Roger’s copy’ in biro, a reference to Jones’s synthesizer programmer, Roger King. Pages 5 to 18 comprise very detailed handwritten information relating to cue locations, synthesizer patches, timings and general musical characteristics.

Cue 1M1 (Main Title) from page 5 is indicative of the approach. The descriptive text reads:

MAIN TITLE. ENIGMATIC “TOOL KIT” CUE STARTS IN BLACK AT TOP OF SHOW AND CONTINUES OVER FADE UP TO EERIE LANDSCAPE AS BIZARRE CONVOY APPEARS ON SMOKE SHROUDED HIGHWAY. MAIN TITLE CARD WILL FOLLOW MUSHROOM SHAPED LAB TRUCK BREAKING THRU FOG. THREAD OF CUE SHOULD CONTINUE ACROSS SCENE IN JULIE’S APARTMENT: A SLOW PAN ACROSS MANTLE LADEN WITH PERSONAL EFFECTS TO REVEAL JULIE AND ALEX IN BED. THIS SCENE IS STILL TO BE CUT, BUT GEOFF [Murphy the director] SAID THAT IT SHOULD BE “EMOTIONALLY BRIGHT”. ALARM CLOCK GOES OFF AND MUSIC IS OUT. NOTE: TIMING IS APPROXIMATE.

In the margins of the typewritten notes, a number of handwritten comments have been added in biro:

At the end of the notes for each cue, a very brief indication of the underlying expressive or affective content has been provided in a different hand to the notes on the left-hand side of the pages. Examples of these descriptions include: ‘enigmatic, intriguing, towards ominous’ (1M1), ‘tension building suspended after chord’ (1M5), ‘disorientation – action’ (2M2), ‘celestial’ (3M2), ‘exotic’ (3M3S), ‘poignant – sad’ (5M3) and ‘melancholy’ (6M3S).

‘Sync Pop’ Placements

These two pages consist of handwritten information faxed from ‘Freejack editorial’ on 17 and 19 December 1991. They involve a list of cue numbers, film position timings in both feet and frames, SMPTE timecode and a brief description of the visuals for the start-point of each cue. For example, the fifth item in the list sent on 19 December is given as follows:

5M2 248+8 02:45:19 A. [Alex] up stairs

The ‘pops’, ‘pips’ or ‘beeps’ listed on this chart indicate the placement of a brief burst (1/15th second) of 1000Hz tone which is used to synchronize (or lock together) sound and picture during editing.

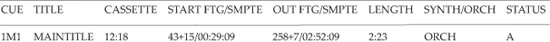

Scoring Log 12/19 Revision

A two-page scoring log (or session report) is dated 19 December [1991]. This consists of a table of cues running from 1M1 to 12M4. For each cue in the table, the following information is supplied: cue number, title, audio cassette, start footage and timecode position, out footage and timecode position, length, synth/orch, status. For example, the first field appears as follows:

Multitrack Track Sheets

This figure has intentionally been removed for copyright reasons.

To view this image, please refer to the printed version of this book.

Figure 1.1 Multitrack sheet for cue 3M1

Each cue has an individual track sheet associated with it (see Fig. 1.1 for cue 3M1); these identify the names of the composer (Trevor Jones), the engineers (Roger King and John Richards) and technical/musical information. Many of the multitrack notes provide technical synchronization information (for example, in 1M3 the position of the ‘sync pip’ is given). However, others present more detailed expressive data, especially those found in relation to cues 3M1 (‘Switchboard Ambience’), 3M2 (‘Nun with a Gun’) and 4M1 (‘Brad’s Place’). Tracks 1 and 3 of cue 3M1, are noted to contain the ‘spiritual switchboard atmosphere’, and 4 and 6 a sting occurring on McCandless’s disappearance. In the notes, the cue is defined as providing a ‘gossamer atmos’. The spotting notes for 3M2 report that the ‘cue may be ecclesiastical but should not be mistaken for source organ’, and this is reinforced by the multitrack notes which indicate that ‘although not meant to sound like an organ source cue we are trying for an ethereal/celestial feel’.

The use by Jones of ‘toolkits’ of what he describes as atmospheres created on the Synclavier in some of his film work is of particular interest. The composer described the process to Ian Sapiro as follows:

The idea of ‘toolkits...