![]()

1

The Value of Historical Perspective1

Monica H. Green

This chapter looks at the history of global health not as an interdisciplinary field of academic study or an aspect of public policy, but rather as the history of health globally.2 What is to be gained from such a massively encompassing perspective? What does the history of health – or rather, the history of threats to health and those health-seeking behaviours meant to restore it – offer researchers and policy analysts who are faced in the most urgent way with present ill-health and future threats of disease? And what, especially, is to be gained from going into ‘deep history’ rather than simply the past decade or century?

I argue that it offers a sense of scope and a sense of scale, a sense that we are part of a larger narrative whose trajectory we can only partially direct. The past is and will always be with us. Pathogens themselves have histories – coded in their very DNA – and many aspects of disease as it manifests itself in the present-day world have deep roots. Where diseases are found, in which populations, at what levels of prevalence, are factors of the current epidemiological landscape that have been influenced, in many cases, not simply by the accidents of birth or the behavioural choices of living human populations, but by the patterns of migration and cultural developments of humankind over many millennia. What we see in our present-day world (as rapidly changing as it is) are the epiphenomena of evolutionary forces, human culture and sheer accident. Recognizing that we are simply standing at the current peak of an ever-changing landscape in our relations with the microbial world, our habitats and our own genetic makeup is critical to developing realistic agendas for what we can and might dream to do in terms of global public health interventions.

The reasons for ‘going global’ in this analysis are simple: as a species we have been global for millennia, and the diseases to be examined here are (and in many cases, have long been) global in their dissemination. But why ‘think deep’ when much of the international policy and nearly all of the biomedical science driving global health initiatives is itself only a few decades (or even a few years) old? The World Health Organization Fact Sheets for most diseases jump in their narratives from first presentation of the disease to modern therapies: for example, the ‘facts’ for leprosy jump from the first known written reference to leprosy c.600 BCE to the discovery in 1940 of dapsone (the mainstay of the multi-drug therapy used for the disease worldwide) (WHO 2010c).3 Why do we need to know more than the recent narrative, the point at which we could do something about disease?

That question presupposes, first of all, that humans have never done anything about disease or ill-health prior to the invention of modern medicine. That is a patently false assumption; indeed, evolutionary biologists are now asking whether health interventions should be counted among those activities that contributed to hominin development.4 The second, and more important, reason is that diseases have histories far beyond the awareness of modern bioscience. Every disease is a veritable iceberg of history, only the peak of which we can see in our modern scientific and biomedical perceptions.

Consider the case of HIV/AIDS. Typical histories of the disease will start their chronological clock in 1981, when the first case reports were published in the United States Weekly Morbidity and Mortality Report linking a cluster of symptoms found in young adult males in California. The narrative then builds from those early days of epidemiological confusion and public panic to identification of the causative organism in 1983–84, the development of biomedical therapies and public health initiatives in the mid to late 1980s, and so on (for example, Fauci 2008). Yet we know now that HIV’s biological and social history in humans is much longer than that, going back several more decades into the early twentieth century and connecting to patterns of hunting, urbanization, labour migration and changing marital, sexual, and probably medical practices in western Africa. That narrative is also geographically broader than the axes of Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, Haiti and Western Europe that seemed to be epicentres of the disease in early epidemiological conceptions. This deeper historical perspective has been critical not simply to our understanding of the disease as a zoönosis of African origin and considerable genetic diversity (Sharp and Hahn 2008; Worobey et al. 2008),5 but also for our understanding of human social and sexual practices and migratory activities throughout much of the world. In other words, the post-1981 narrative is not wrong, but it is incomplete in ways that, sadly, help explain why the pandemic was at many levels contained in North America and Western Europe by the late 1990s but, until incidence levelled out in 2010, continued to explode in other parts of the world and continued, as of 2011, to devastate sub-Saharan Africa. The metaphor of the iceberg was, in fact, already used by HIV/AIDS researchers by 1985 to warn of the potential epidemiological breadth of the disease’s spread beyond the visible group of extremely ill patients who were already presenting to clinicians (NIH 1985; Fauci 1986). The metaphor works equally well to convey the chronological depth of disease histories. HIV/AIDS’s ‘iceberg’ is relatively shallow in chronological terms: its worldwide presence today owes much more to its emergence in the period of jet travel and its own rapidly evolving nature than to its age as a pathogen in humans. Other diseases, in contrast, have ‘icebergs’ that extend back to our origins as a species. Seeing how huge a historical iceberg lies below the surface of disease entities as they manifest themselves in the present day is humbling, but understanding the depth of the ‘roots’ of disease may transform our sense of the challenge before us.

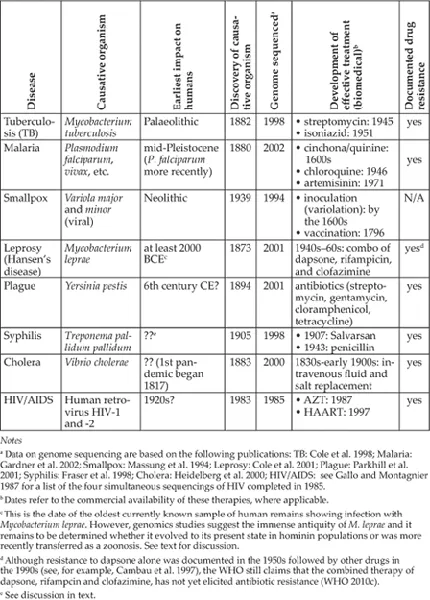

A Framework for Analysis

The present chapter summarizes the perspectives on the global history of health that I, a historian of medicine, and a colleague, Rachel Scott, a bioarchaeologist, have developed in a course we teach at Arizona State University. The course is designed to offer a framework for thinking about the global history of human health by using two analytical approaches simultaneously. First, we frame the course chronologically and conceptually around the notion of the three epidemiological transitions: major shifts in the types and prevalence of diseases due to changes in human social and cultural practices. This is a concept formulated by the medical anthropologist and epidemiologist George Armelagos and a series of colleagues over the course of the past two decades (Armelagos 1990; Barrett et al. 1998; Armelagos et al. 2005; Harper and Armelagos 2010). Building on the concept of a single epidemiological transition first proposed in 1971 (for distinctly different purposes) by Abdel R. Omran (Omran 1971; cf. Weisz and Olszynko-Gryn 2010), Armelagos suggests that the modern history of the human species can be seen as turning on three key points of transition between the late Pleistocene and the present day. Second, to fill in that broad chronological canvas we chose eight ‘paradigmatic diseases’: infectious diseases whose biological character, historical accidents and evidentiary records made them exemplary of larger trends in human history. In some cases, these are diseases distinctive for the high mortality or morbidity they have caused (tuberculosis (TB), malaria, smallpox, cholera and, perhaps the greatest killer of all, plague); in others, for the larger effects they have had on social practices and institutions, and the development of notions of stigma (leprosy, syphilis and HIV/AIDS). Wherever they originated, these eight diseases sooner or later impacted all inhabited parts of the globe. Table 1.1 summarizes the key characteristics and chronologies of each of them. With the exception of HIV/AIDS, all of these diseases have woven in and out of the narrative of human history multiple times. And with the exception of smallpox, all are still with us. Together, therefore, the framework of the epidemiological transitions and the dramatis personae of our eight diseases allow us to encompass the entire global history of human health.

Framing Human Time and Culture

The first epidemiological transition is identified with the beginnings of human agriculture and settled society, starting around 10,000 years ago. Humans were subject to diseases before the transition to agriculture, of course. In tracking Homo sapiens sapiens out of Africa and into Asia, the Pacific and the western hemisphere, Armelagos uses the concepts of ‘heirloom’ diseases, those passed down from generation to generation of humans (and in some cases, earlier hominins), and ‘souvenir’ diseases, those acquired on travels into new ecological niches. The transition to agricultural, settled society obviously happened at different times to different human populations – or not at all, in the case of those hunter-gatherer societies that have kept their traditional ways of living up to the modern period.6 The commonality for settled populations, of course, was the ability for diseases to flourish in human hosts in ways they had never done before because (a) changes in nutrition due to reliance on domesticated crops probably lessened populations’ resistance to infectious diseases; (b) sedentism meant not simply more closely confined living arrangements, but also greater transmission of those diseases that were acquired because people lived in their own waste instead of migrating seasonally to new, clean grounds; and (c) the domestication of animals allowed the transmission of zoönoses with a new regularity.

Table 1.1 Eight paradigmatic infectious diseases

Most of the history of human populations from the beginnings of sedentism up through the nineteenth century falls into this long phase of the First Epidemiological Transition. Although both malaria (or at least certain kinds of it) and tuberculosis infections afflicted human populations long before the transition to agriculture, both diseases flourished with new effectiveness in these larger, settled populations. As large urban societies developed beginning in the third millennium BCE, we find our first evidence of the new ‘crowd’ disease of smallpox. Leprosy and plague both seem (in our current understanding) to have their origins in Asia, and become the emblematic ‘medieval’ diseases because of the unification of Eurasia by regularized trade that tied the urban cultures of East and Southeast Asia to those of the Middle East and, increasingly, Western Europe and sub-Saharan Africa. With the Columbian Exchange and the move into the colonial empires, we get not simply the well-studied spread of smallpox into the New World, but apparently the first global impact of syphilis, leprosy and cholera, whose pre-global histories are still not well understood. Even malaria is likely to have become ‘global’ only in this period.7

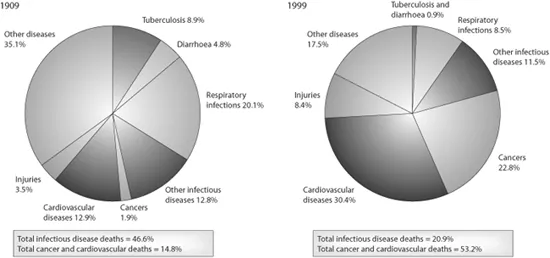

The second epidemiological transition (essentially identical to the one Omran first sketched) is the shift between the nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries from infectious diseases as being the leading causes of death to chronic or ‘lifestyle’ diseases: heart disease, diabetes, cancer and so on. (Figure 1.1 gives a summary of these shifts in Chile.) An important part of our narrative is that almost all the ‘old’ infectious diseases became far worse in their impact before the Second Transition. They not only affected naïve indigenous populations for the first time (smallpox, leprosy and probably new strains of TB), but even the European metropoles were more grievously afflicted than they had ever been in the past, both by the frequent waves of the ‘emergent’ disease of cholera and by rising incidence of TB. (Plague had disappeared from Western Europe by 1722 and leprosy had retracted to Europe’s northern periphery.) Even smallpox, despite dissemination of inoculation techniques from the early eighteenth century and then at century’s end Jennerian vaccination, increased its spread in this period.

Jennerian vaccination did eventually lead to containment of smallpox in many parts of the industrializing world by the late nineteenth century, though the most important element in the arrest of infectious disease was surely the sanitation measures implemented by western governments in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Germ theory (a product of the late nineteenth century) was more important in aiding those sanitation efforts than, at least initially, in providing effective medicines, although one should not discount the role of biomedical techniques to test for disease, which played a vital role in developing public health policies.8 Like the first epidemiological transition, the second came to different societies at different times, and many of the world’s societies have still not experienced a period where controlled systems of water supply, waste disposal and housing reform – along with the benefits gained by widespread vaccination practices and (to a lesser degree) the impact of antibiotics and other therapeutic interventions – have brought about a shift to ‘lifestyle’ and genetic diseases as major causes of death.

Figure 1.1 Proportions of total deaths from major cause-of-death categories, 1909 and 1999, in Chile.

Source: Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: R.A. Weiss and A.J. McMichael, (2004), ‘Social and environmental risk factors in the emergence of infectious diseases’, Nature Medicine 10, S70–S76.

The third epidemiological transition, as defined by Armelagos and his colleagues, has followed the second very quickly, and we are in the midst of it now. This period is characterized by new, emerging infectious diseases (HIV/AIDS, Ebola, SARS, avian flu and so on); re-emerging infectious diseases (most especially TB and malaria, heightened in their lethality by HIV co-infection); and the development of widespread antibiotic resistance by almost all the major pathogens. The third epidemiological transition has six principal contributing factors: ecological changes; human demographics and behaviour; increasingly rapid international travel and commerce; technology and industry; microbial adaptation and change; and the breakdown in public health measures that had been so instrumental in the Second Transition.

A Multi-Disciplinary Approach: Taking the Materiality of Disease Seriously

The theory of the three epidemiological transitions is useful to us primarily as a way of identifying the structural commonalities of various human cultures and disease environments across time and space. But what really makes our narrative ‘global’ is that each of our paradigmatic diseases does indeed have a global history. In contrast to most approaches to the history of medicine, where historians (myself included) have largely eschewed what we call ‘retrospective diagnosis’, in this course we start from the premise that we know what the disease is biologically and that its biological character is essential to our understanding of its historical impact. In this respect, the diseases (or rather the pathogens that cause them) function as ‘historical actors’ – not rational ones, of course, but ones with distinctive ‘personalities’ that help us understand the timing, environmental circumstances and material phenomena (including visible symptoms) that humans would have faced in dealing with them. In fact, we ourselves reject traditional types of retrospective diagnosis for the same reasons as most historians of medicine: because they have for the most part been based on the interpretation of words used to describe disease in written records from the past (Arrizabalaga 2002). Those words are reflective less of some permanent physical reality than of the intellectual concepts of disease categorization prevailing at a given historical moment in a particular cultural context. Hence, retrospective diagnosis has often been little more than a parlour game concerned to get a diagnosis of past disease ‘right’ within the categories used by biomedicine at the moment the historian is writing.

Rather, we approach our eight paradigmatic diseases from a belief in their biological reality and from a belief that there are scientific methods that can assess that reality in the past, including evolutionary change over time, in ways that obviate reliance on verbal traces alone. The genomics revolution is one of the developments that allows us to think differently now about the history of disease. The first virus was sequenced in 1975, followed in 1995 by the first complete sequencing of an independently living pathogen.9 Most of the pathogens known to afflict humans, including all eight of our paradigmatic diseases, have now been sequenced (see Table 1.1). In every case, a whole new world of genomic investigation has opened up owing to the development of polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which allows continual multiplication of genetic material, and to high-throughp...