![]()

INTRODUCTION

Maternal sensitivity: observational studies honoring Mary Ainsworth’s 100th year

Klaus E. Grossmanna, Inge Brethertonb, Everett Watersc and Karin Grossmanna

aDepartment of Psychology, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany; bDepartment of Human Development and Family Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA; cDepartment of Psychology, State University of New York, Stony Brook, NY, USA

This special double issue of Attachment & Human Development celebrates and honors Mary D. Salter Ainsworth and her lifetime achievements on the 100th anniversary of her birth. The papers we have invited focus on maternal sensitivity, broadly construed, and its links to the development of secure and insecure attachment. Mary Ainsworth’s contributions to this important topic have been central and enduring.

Mary Ainsworth spent the years 1949–1953 working with John Bowlby and James Robertson at the Tavistock Institute in London, where one of her tasks was to analyze Robertsons’ field notes in which he had recorded his observations of children who were separated from their families for shorter or longer periods. She described his notes as “the most sensitive and perceptive direct observations I had ever encountered,” but Robertson did not allow her (as a psychologist) to “transgress into direct observations” because she had not been trained (Myers, 1969).

Thus, when Mary Ainsworth moved to Uganda with her husband Leonard, in 1954, she eagerly seized the opportunity to conduct her own home observations of mother–infant interactions in a non-Western culture. She emulated Robertson’s skilful observational methods, but, on the theory side, she was influenced by ethological studies of social bond-formation in animals that John Bowlby had begun to incorporate into this emerging Darwinian approach to infant–mother attachment (Bowlby, 1953). Bowlby’s views persuaded her, once she began observing, to drop the “theory of cupboard love” (that babies love their mother because mothers feeds them).

The Uganda study (Ainsworth, 1967) yielded a number of important insights and findings regarding the development of attachment and the use of the mother as a secure base. She built upon and extended this work in her Baltimore longitudinal study, where she and her research team implemented a much more detailed system for observing mother–infant interactions in real life situations. Observer notes taken during lengthy 3-weekly visits throughout the infant’s first year were translated into audio-recorded narratives and then transcribed. The resulting narrative records allowed Mary Ainsworth to identify four key dimensions of maternal care: sensitivity-insensitivity, cooperation-interference, acceptance rejection and accessibility-ignoring/neglecting and to develop corresponding rating scales (Ainsworth, 1969). Overall ratings of the 9–12 months narrative records turned out to be strong predictors of infant–mother attachment security in the Strange Situation at 1 year of age (Ainsworth, Bell, & Stayton, 1971; Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978).

It often goes unrecognized that Mary Ainsworth’s evaluation of maternal care as adapted to an individual infant’s characteristics was revolutionary. The phylogenetic programme is sufficiently open to allow all babies to become attached to caregivers, even if the quality of care they receive is insensitive or even abusive. Infants’ attachment to the caregiver under these circumstances, however, is likely to be insecure. Sensitivity, hence, is a key to understanding the development of individual differences in attachment relationships. As Mary Ainsworth later said, observational research on maternal sensitivity, broadly construed in ethological terms, was an entirely different paradigm from then current behaviorist notions that sensitive responding amounts to spoiling a baby (Ainsworth & Bell, 1977).

In the late 1960s Klaus Grossmann began to read about John Bowlby’s ethological orientation and the observational studies of preverbal infants by Mary Ainsworth and her research team. In 1973, having acquired a doctorate in ethology, he expressed an interest in learning the new methods, and Mary Ainsworth invited him to her Baltimore lab where she and her research team shared insights and transcripts and demonstrated the Strange Situation. Inspired by Klaus’ reports of his Baltimore visit, Karin Grossmann initiated a 1-year observational pilot study of six mothers and babies in their homes in Bielefeld, Germany. In 1975, with Mary Ainsworth’s encouragement, the Grossmanns began a larger longitudinal study whose methods during the first-year phase were closely modeled on those used in Baltimore. The Bielefeld study confirmed that many detailed findings obtained in Baltimore (Ainsworth et al., 1978) held also in North Germany (K. Grossmann, K. E. Grossmann, Spangler, Suess, & Unzner, 1985). Longitudinal studies in Regensburg followed (K. Grossmann & K. E. Grossmann, 2012; K. Grossmann, K. E. Grossmann, & Kindler, 2005). Throughout this work the Grossmanns were generously helped by Mary Ainsworth and her former graduate students, particularly Mary Main, who classified Strange Situations, and Inge Bretherton, who acted as reliability rater of maternal sensitivity for Bielefeld home visit narratives. In the mid-1970s a number of other influential longitudinal attachment studies were initiated in Minnesota, Berkeley and Israel, demonstrating that Ainsworth’s insights and methods travelled well (see summaries in K. Grossmann, K. E. Grossmann, and Waters, 2005).

The Grossmanns’ longitudinal research, and that by others too numerous to cite here, showed that parental sensitivity can be observed well beyond infancy. They found that sensitive parents not only respond with prompt and appropriate behavior, but interpret and give words to their children’s feelings and experiences. They serve as translators between child and environment, and between the child and her peers or other adults, and for this reason caregiver sensitivity has become pivotal to attachment-based clinical interventions with troubled families.

Over and above responding to an infant’s or child’s needs for protection and affection, sensitivity, as conceptualized in Mary Ainsworth’s scales, also involves respect for the child as a valuable person with autonomous feelings, needs, wishes, goals and a mind of her own. To the child, a caregiver’s sensitivity means that her or his communications are understood, worthy of attention, and appropriately and promptly responded to. In addition, a caregiver’s sensitive responses foster the child’s competence.

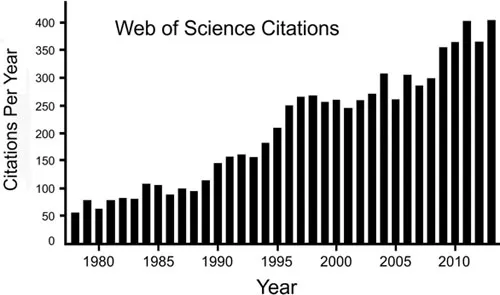

Given the complexity of the sensitivity construct, however, the scientific assessment of caregiver sensitivity remains a challenge. One problem has been the availability of the four scales. Only the text of the Sensitivity-Insensitivity scale has been published in full (Ainsworth, Bell, & Stayton, 1974). Although the complete instructions for the full set of four scales have long been available in mimeographed form and online (Ainsworth, 1969), the whole set will appear in print for the first time in a new edition of Ainsworth et al.’s classic volume, Patterns of Attachment, scheduled for 2014. In the 100th year after Mary Ainsworth’s birth, and almost exactly 60 years after the beginning of the Baltimore Study in 1964, it is clear that her work on maternal sensitivity and infant attachment is more relevant than ever. Her observations and insights have generated an entire new field of study and, as noted by Howard Steele, “this journal would not exist without her” (personal communication, July 2013). Moreover, as Figure 1 documents, interest in Mary Ainsworth’s work over the years has only increased.

Figure 1. Number of citations per year of Mary Ainsworth’s publications. (Web of Science 1978–2013).

Mary Ainsworth’s productive influence is also evident in the contributions to this Special Issue by eminent researchers who have creatively extended and elaborated the construct of caregiver sensitivity-insensitivity and its relation to secure and various insecure forms of attachment.

We open this special double issue of Attachment & Human Development with Mary Ainsworth’s own account of her life, work and career. Although her 1983 autobiographical essay is not widely known, it conveys both her commitment to her work and her concern for children and mothers. It is followed by two reviews. In the first review, Inge Bretherton provides a thoroughgoing summary and analysis of the complete corpus of work by Ainsworth and her Baltimore research team that relates to the sensitivity construct, the scales and the link between maternal sensitivity and infant security. In the second review, Judi Mesman and Rosanneke Emmen describe and analyze eight of the most commonly used global assessments of caregiver sensitivity. The remaining contributions illustrate various new applications of the sensitivity construct. Kristin Bernard, E. B. Meade and Mary Dozier show how assessment of sensitivity in distress and non-distress situations can be used in vivo during clinical interventions with troubled families. Elizabeth Meins documents how sensitivity manifests itself in a mother’s ability to empathize with her infant’s feelings and internal states, revealed by appropriate versus inappropriate mind-minded verbalizations during interactions with a preverbal infant. David Oppenheim and Nina Koren-Karie demonstrate how facets of sensitivity are revealed in mothers’ talk about the relationship with their child as they respond to questions about a video-taped interaction with their child. Karlen Lyons-Ruth and her colleagues report that, in high risk groups, maternal withdrawal – a neglected facet of insensitivity – predicts D-secure patterns of attachment in infancy, controlling-caregiving attachment in middle childhood and adolescent psychopathology as well as maternal role confusion at age 20. Beatrice Beebe and Miriam Steele show that derailed dyadic communication processes, observed micro-analytically during brief mother–infant face-to-face interactions at 4 months, already foreshadow the infant’s disorganized attachment classification at 1 year. Along very different lines, Alexandra Voorthuis and colleagues assessed sensitivity in female college students who were asked to provide care to a standard “difficult baby” (simulated by a programmable robotic doll). Sensitivity scores were stable across settings and related to positive affect while caring for the doll. Joan Stevenson-Hinde, Rebecca Chico, Anne Shouldice and Camilla Hinde showed that multiple assessments of sensitivity in different contexts provide stronger predictions of attachment security than single assessments and mediate the link between maternal anxiety and security in a study of preschoolers. German Posada assessed maternal sensitivity in several contexts (home, hospital, and playground) in infants and preschoolers. Sensitivity ratings in different situations were correlated with each other and children’s secure base behavior. He demonstrates the validity of the sensitivity construct in Latin America, even when assessed ethnographically. Finally, Gottfried Spangler presents evidence that some potentially deleterious gene polymorphisms associated with emotion regulation have an adverse developmental effect primarily under conditions of maternal insensitivity. Also notable, several authors were able to go beyond the secure/insecure dichotomy and document that specific aspects of insensitivity predicted insecure-avoidant, -resistant, and -disorganized attachment patterns. The epilogue for the Special Issue by Everett Waters and co-authors indicates that there is a great deal of work ahead and ample opportunities to make significant contributions built upon Mary Ainsworth’s work.

We wish to express our deepest thanks to all contributors who participated in the arduous and exciting effort to produce this Special Issue. In addition, we gratefully acknowledge the unstinting and responsive support by the editor of Attachment & Human Development, Howard Steele. We also thank Taylor & Francis who contributed in many ways to making this Special Issue possible.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1967). Infancy in Uganda: Infant care and the growth of love. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1969). Scales for home visits. Retrievable as “Sensitivity scales” from http://www.psychology.sunysb.edu/attachment/measures/content/ainsworth_scales.html. Also available from the Harvard Dataverse Network (Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Attachment 1963-1967).

Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Bell, S. M. (1977). Infant crying and maternal responsiveness: A rejoinder to Gewirtz and Boyd. Child Development, 48, 1208–1216.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Bell, S. M., & Stayton, D. J. (1971). Individual differences in Strange Situation behaviour of one-year-olds. In H. R. Schaffer (Ed.), The origins of human social relations (pp. 17–57). London: Academic Press.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Bell, S. M., & Stayton, D. J. (1974). Infant-mother attachment and social development: “Socialization” as a product of reciprocal responsiveness to signals. In P. M. Richards (Ed.), The integration of a child into a social world (pp. 99–135). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the Strange Situation. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bowlby, J. (1953). The contributions of studies of animal behavior. In J. M. Tanner (Ed.), Prospects in psychiatric research (pp. 80–108). Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications.

Grossmann, K., & Grossmann, K. E. (2012). Bindungen - Das Gefüge psychischer Sicherheit [Attachments - The framework of psychological security] (5th ed.). Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta.

Grossmann, K., Grossmann, K. E., & Kindler, H. (2005). Early care and the roots of attachment and partnership representation in the Bielefeld and Regensburg Longitudinal studies. In K. E. Grossmann, K. Grossmann, & E. Waters (Eds.), Attachment from infancy to adulthood: The major longitudinal studies (pp. 98–136). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Grossmann, K., Grossmann, K. E., Spangler, G., Suess, G., & Unzner, L. (1985). Maternal sensitivity and newborns’ orientation responses as related to quality of attachment in northern Germany. In I. Bretherton & E. Waters (Eds.), Growing points in attachment theory and research. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50 (1-2, Serial No. 209), 233–256.

Grossmann, K. E., Grossmann, K., & Waters, E. (Eds.). (2005). Attachment from infancy to adulthood: The major longitudinal studies. New York, NY: Guilford.

Myers, R. (1969). Interview of Mary Ainsworth. Oral history of psychology in Canada. Retrieved from www.feministvoices.commary-ainsworth

![]()

Mary D. Salter Ainsworth: an autobiographical sketch

Reprinted from: O’Connell, A. N., & Russo, N. F. (Eds.). (1983) Models of achievement: Reflections of eminent women in psychology (pp. 200–219). New York: Columbia University Press.

© 1987 Agnes N. O’Connell, Nancy Felipe Russo. Reproduced with permission of Nancy Felipe Russo.

If this were a clinical history rather than a brief sketch of a career, it would begin with my family, and continue to discuss in detail my relationships with my parents and two younger sisters as they changed in the course of my development. Except for stating that we were a close-knit family with a not unusual mixture of warmth and tensions and deficiencies, I shall confine myself to a few bare facts.

My parents were Pennsylvanians, both graduates of Dickinson College, where my father earned a Master’s degree in history before he went to work for a large manufacturing firm in its Cincinnati office. My mother groped for a vocation after her graduation, tried teaching, began nursing training, then was called home because of her mother’s illness. Five years after her graduation she married my father, and henceforward had no thought of a career other than homemaking. I was born late in 1913, and my sisters two and seven years later, respectively. In 1918 the family moved to Toronto, my father having been transferred to a Canadian branch of his company. Later the foreign branches split from the parent company, and in due course he became president of his branch. Realizing that he was committed to a career in Canada, he became a naturalized citizen, as did I as a minor.

From the beginning it was assumed that we girls wo...