eBook - ePub

The Middle East

A Geographical Study, Second Edition

- 638 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Middle East

A Geographical Study, Second Edition

About this book

This book, first published in 1976 and in this second edition in 1988, combines an examination of the political, cultural and economic geography of the Middle East with a detailed study of the region's landscape features, natural resources, environmental conditions and ecological evolution. The Middle East, with its extremes of climate and terrain, has long fascinated those interested in the fine balance between man and his environment, and now its economic and political importance in world affairs has brought the region to the attention of everybody.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

Relief, Geology, Geomorphology and Soils

1.1 Relief

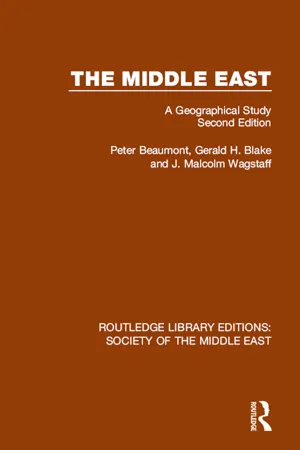

In a region as large and diverse as the Middle East, it is difficult to describe topographical conditions in a simple way. However, relief factors have played an important and often directly controlling role on the human occupancy of the region, and it is, therefore, essential that at least a brief sketch is given of the major features. For convenience the region can be divided into a northern mountainous belt, comprising the states of Turkey and Iran, and a southern zone made up largely of plains and dissected plateaus (Figure 1.1).

In Turkey, two major, though not continuous, mountain belts are usually recognized. The Pontus Mountains are an interrupted chain of highlands paralleling the Black Sea coast. They rise in altitude in an easterly direction to heights of more than 3000m south of Rize. Inland from the southern coast of Turkey is the much more formidable range of the Taurus Mountains. Being less dissected by river systems than their northern counterparts, these uplands have always presented a considerable barrier to human movement, so focusing routes through passes such as the Cilisian Gates, to the northwest of Adana. Between the two ranges the central or Anatolian Plateau lies sandwiched. This is almost every-where above 500m in height and relatively isolated from the coastal regions.

In eastern Turkey the Pontus and Taurus ranges coalesce in a complex upland massif near Mount Ararat (5165 m) where crest elevations surpass 3000m. From here eastwards into Iran the mountain chains divide once more. In the north along the southern shore of the Caspian Sea are the Elburz Mountains, which in Mount Damavand (5610m) contain the highest peak of the region. Although these uplands are relatively narrow in a north to south direction, they present the greatest barrier to human movement anywhere in the Middle East. Southwards from Mount Ararat, overlooking the Tigris–Euphrates lowlands and the Gulf, stretch the broad Zagros Mountains. They attain a maximum height of 4548m in Zard Kuh. These parallel ranges with their wide upland valleys have never presented the same degree of difficulty of movement as the Elburz.

In eastern Iran, on the borders of Afghanistan, a very complex pattern of mountain ranges, usually described as the Eastern Iranian Highlands, are found. These are lower than both the Elburz and Zagros Mountains, attaining only 2500m in altitude. Surrounded by these highlands is the Central Plateau of Iran. This, like the Anatolian Plateau, is almost everywhere above 500m in height, and is subdivided into two major basins both of inland drainage. The Dasht-e-Kavir forms a huge salt desert in the north, while the term Dasht-e-Lut is used for the southern basin.

Figure 1.1 Major relief features of the Middle East and North Africa

In the southern region of plains and dissected plateaus a useful east/west division can be made along the line of the Red Sea and the Suez Canal. In eastern Egypt the Red Sea Hills are the major upland area, while the Nile delta forms the major lowland. To the west, a relatively simple topographical picture can be drawn, with narrow lowlands along the coast rising inland to upland plateaus along the southern margins of Libya and Egypt. Even on these interior plateaus heights of more than 1000m are rarely surpassed. Large sand seas form important landscape features in this zone. An important exception to this general description is the existence of a small upland zone, the Jebel el Akhdar, in northeast Libya. Although only some 1000m in height this region has played an important role in the human settlement of the region.

To the east of the Red Sea the highest land in this zone is found at the south-western corner of the Arabian peninsula. Here in Yemen altitudes of more than 3700m are attained. Highland also occurs along the whole of the western part of Arabia, with the general level of the land declining to the north and east. In central Arabia, characteristic features of the relief are a series of westward facing escarpments, in arc-like form around the main highland mass of the west coast. Although none of these landforms are particularly high they have concentrated the routes across the peninsula towards the regions of most easy access. In the Levant, upland areas are found in proximity to the coast, with a gradual decline in altitude towards the interior. Heights here too can be considerable, reaching almost 3000m at Mount Hermōn. The pattern of relief in this region is complicated by the existence of the north-south fault zone of the Dead Sea Lowlands, which has dissected the upland belt to form a trough-like region descending to 300m below sea level.

Stretching from northern Iraq to the coast of the Indian Ocean in Oman is the largest lowland belt of the region. In Iraq it is crossed by the large rivers Tigris and Euphrates and in the southern parts relief is minimal. Some of the oldest human settlement in the world is found here. The lowland belt continues as an attenuated zone along the western shore of the Gulf to broaden into an extensive plain in southeastern Arabia. In this latter zone the largest sand sea in the world, the Rub’al Khālī, is situated. Here some of the dunes are more than 200m in height. At the easternmost tip of Arabia, a belt of uplands, also called Jebel al Akhdar (‘Green Mountain’) reach a maximum height of more than 3000m. This region has always been an extremely isolated part of the region cut off by both sand and water from adjacent areas.

1.2 Geology

In recent decades our knowledge of the evolution of the continental masses has increased tremendously owing to detailed geological and geophysical investigations in many parts of the world. As a result of this work new theories of sea floor spreading and plate tectonics have been put forward, and widely accepted by most earth scientists.1 The basic idea of these theories is that the continental masses are embedded in huge plates which move over the denser material beneath the earth’s crust. These plates, and the continents on top of them, travel across the surface of the earth probably as the result of convectional currents acting deep within the earth. This movement can lead to the plates coming into contact with one another, so producing crush zones, or mountain ranges. In such contact zones, parts of one or other of the colliding plates are dragged down towards the centre of the earth, along what are termed Benioff or subduction zones. In contrast, where two plates are moving away from one another, upwelling of magma occurs usually beneath the ocean floors, to produce sea floor spreading.

Geologically speaking, the Middle East and North Africa is a particularly complex region, as a number of different continental plates have come into contact here. North Africa and Arabia represent the remnants of an ancient continental landmass in the southern hemisphere known as Gondwanaland. During the Mesozoic period this landmass, composed mainly of Palaeozoic and older rocks, began to split up and drift northwards. Eventually these moving continental plates made contact with a similar landmass in the northern hemisphere, known as Laurasia. When this occurred, probably during the Tertiary period, the younger sediments which had formed between and overlapped onto the ancient and stable continental platforms in the Tethyan Sea, buckled and contorted as the result of compressive stresses to produce the mountain ranges which stretch through the region from the Alps to the Himalayas. Although this simple picture of events gives a reasonable idea of what happened, a glance at a detailed geological map illustrates just how complex the real situation is. Indeed, it is still true to say that the exact inter-relationships of the different continental plates in the region are not known with any degree of certainty.

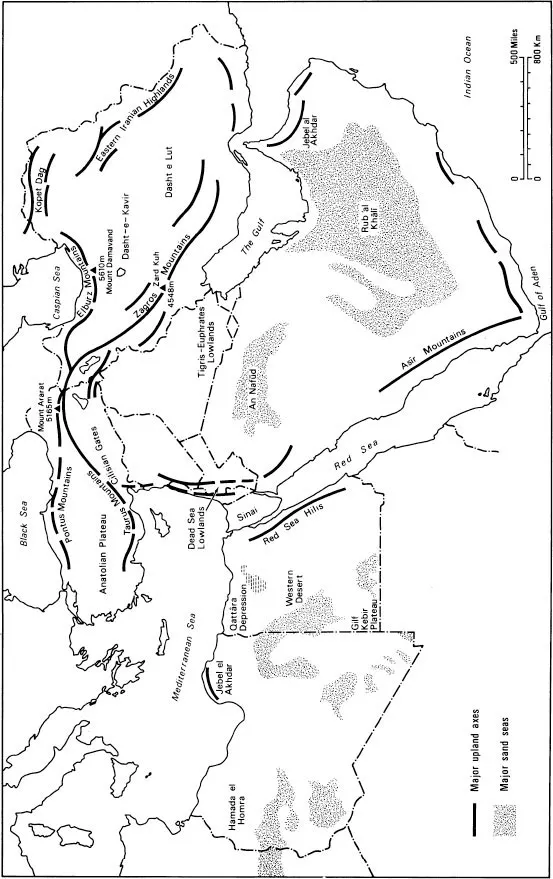

In the Mediterranean and Middle Eastern region three major plates can be identified. These are the African, Eurasian and Arabian plates, and the boundaries between them are the Azores–Gibraltar ridge and its extension across North Africa, the Red Sea, and the Alpide zone of Iran (Figure 1.2).2 Seismic activity in Yugoslavia, Greece and Turkey is much more pronounced than in the western Mediterranean. The reason for this appears to be the existence of two small, but rapidly moving plates, named the Aegean and Turkish plates respectively. Observations reveal that the Aegean plate is moving towards the southwest relative to both the European and African plates. As a result of its motion, it is overthrusting the Mediterranean Sea floor south of the Cretan arc and thus causing it to sink beneath the Aegean Sea.

The Turkish plate is moving almost due westwards with respect to the Eurasian and African plates. Its northern boundary is the North Anatolian fault, but the southern limit is not fully defined. The existence of these two small plates and the role they play in the regional tectonics is possibly explained by differences in behaviour between continental and oceanic lithosphere. Material forming the continents is light in density and, therefore, cannot be drawn down into the denser mantle of the earth. When two plates of such material come into contact tremendous energy has to be expended against gravitational forces to thicken the continental crust and so permit crustal shortening. In contrast, the same end result can be achieved and much less energy expended if oceanic lithosphere, composed of denser material, can be consumed by being dragged down into the mantle. This latter is indeed what appears to be happening with the Aegean and Turkish plates, for their motion is such that further overthrusting of continental material is avoided in Turkey, and, instead, Mediterranean Sea floor is consumed in front of the Cretan arc.3 In this way the observed movements of the Aegean and Turkish plates are such as to minimize the work which must be done to move the African plate towards the Eurasian one.

Figure 1.2 Structural units in the Middle East (modified by permission of Nature 1970, 1970)

Further south in the region it has been discovered that three plates also meet towards the southern end of the Red Sea. These are the African, Arabian and Somalian plates.4 In this area it would seem that all the plates are moving away from each other, and that the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden have been formed as the result of sea floor spreading as Arabia moved away from Africa. The rate of movement is thought to be about 1 cm/yr on each side of the rift. Detailed work in the Dead Sea lowlands has revealed that there has been about 100 km left lateral movement on the Dead Sea Fault system since Miocene times.5 What seems to have occurred here is that the Arabian plate has moved northward relative to the small and apparently fixed Sinai plate.6

In Iran it would appear that the northwards motion of Arabia towards Eurasia has been accomplished by widespread overthrusting in a belt from southern Iran to the central Caspian. The net result has been to thicken the continental crust over large areas. Iran can be divided into two regions: the Zagros folded belt, and the rest of the country. In the Zagros region continuous sedimentation under tranquil conditions has occurred from Cambrian to late Tertiary times, when the sediments were folded into a series of parallel anticlines and synclines.7 In contrast, the rest of Iran has suffered more severe epeirogenic movements, as well as considerable igneous and metamorphic activity. Three provinces can be identified in this latter region. The first, the Reza’īyeh–Eşfandegheh orogenic belt runs parallel with the Zagros mountains and unites with the Taurus orogenic belt of Turkey. It is separated from the Zagros Mountains by the Zagros crush zone, which is an area of thrusting and faulting. Centred and eastern Iran, a fault bounded, roughly triangular shaped region with its apex in the south, forms the second province. The Elburz Mountains of northern Iran and the parallel region to the south of them make up the final division of the country.

The northward movement of Africa and Arabia during the Mesozoic caused a reduction in width of the Tethyan Sea. This was achieved by a subduction zone which consumed oceanic crust. Eventually at some time during the late Cretaceous all the oceanic crust disappeared into the mantle and the leading edges of the African and Arabian plates reached the subduction zone. When this occurred ophiolites were emplaced along the Zagros crush zone at the leading margin of the Arabian plate.8 The Zagr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Relief, Geology, Geomorphology and Soils

- 2. Climate and Water Resources

- 3. Landscape Evolution

- 4. Rural Land Use: Patterns and Systems

- 5. Population

- 6. Towns and Cities

- 7. Problems of Economic Development

- 8. Industry, Trade and Finance

- 9. Petroleum

- 10. The Political Map

- 11. Tradition and Change in Arabia

- 12. Iraq – A Study of Man, Land and Water in an Alluvial Environment

- 13. Agricultural Expansion in Syria

- 14. Religion, Community and Conflict in Lebanon

- 15. Jordan – The Struggle for Economic Survival

- 16. Israel and the Occupied Areas: Jewish colonization

- 17. The Industrialization of Turkey

- 18. Iran – Agriculture and Its Modernization

- 19. Egypt – Population Growth and Agricultural Development

- 20. Libya – Oil Revenues and Revolution

- 21. Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Middle East by Peter Beaumont,Gerald Blake,J. Malcolm Wagstaff, Peter Beaumont,G.H. Blake,J. Malcolm Wagstaff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Regional Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.