eBook - ePub

Studies in the Theory of Business Cycles

1933-1939

Michal Kalecki

This is a test

Share book

- 81 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Studies in the Theory of Business Cycles

1933-1939

Michal Kalecki

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume, originally published in 1966, contains essays from the 1930s and is valuable not only in the context of the history of thought. It provides an excellent introduction to the general theory of employment, interest and money and reflect the most essential features of Kalecki's theory of the business cycle.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Studies in the Theory of Business Cycles an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Studies in the Theory of Business Cycles by Michal Kalecki in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Volkswirtschaftslehre & Wirtschaftsgeschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

5. MONEY AND REAL WAGES

PART I (THEORY)

The “Classical” Theory of Wages

1. The assumptions of the “classical” theory of wages may be subdivided into two categories:

(a) The assumption of perfect competition and of the so called “law of increasing marginal cost”. The consequence of this assumption is the association of the rise in employment with a decline in real wages.

(b) The assumption of a given general price level or a given value of the aggregate demand, from which it follows that real wages change in the same direction as money wages.

Now, the cut in money wages being followed by a decline in real wages, and the latter being associated with a rise in employment, the reduction in money wages leads, according to the “classical” theory, to an increase in employment.

Before a critical appreciation of these assumptions we shall describe them in some detail.

2. Let us start from the law of increasing marginal costs and perfect competition. Imagine an establishment with a given capital equipment which produces 100 units of a certain commodity. By increasing employment slightly it may produce 101 units. Now the additional cost of producing the 101st unit, consisting mainly of the cost of raw materials and wages, is called the marginal cost at the level of production equal to 101.

According to the “law of increasing marginal costs”, the marginal cost, i.e. the cost of producing the last unit, rises with the level of output obtained from a given capital equipment. This law will appear to many readers not too plausible and rightly so: whereas in agriculture a disproportionately higher input of fertilizers and labour is required in order to increase the yield, in an industrial establishment the marginal cost starts to rise spectacularly only when maximum utilization of equipment is approached, —which happens to be rather an exception.

We shall examine critically the “law of increasing marginal costs” in the subsequent sections, while at present we shall concentrate on its consequences.

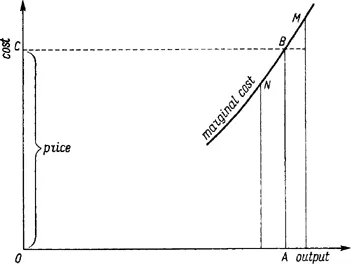

Let us consider a system of perfect competition where a single entrepreneur disregards the fact of “spoiling the market” through his increasing the supply, but considers the price as given. It will be easily seen that the output of an establishment will be pushed up to the point where the marginal cost is equal to the price (on Fig. 5 this level of output is OA).

Indeed, once the entrepreneur increases his output, the marginal cost is higher (according to the “law of increasing marginal costs”) and therefore the cost of production of the last unit exceeds the price (point M is above the straight line CB) and as a result a cut in production will ensue. If, however, the production is below the level at which the price is equal to the marginal cost, the last unit produced yields more than the additional cost involved (point N is situated under the horizontal line CB) and therefore the output will be expanded. The equilibrium is reached when the marginal cost is equal to the price.

FIG. 5

3. Let us now consider a closed economic system. It may be easily shown that if we assume the “law of increasing marginal costs” the aggregate output can expand given the level of wages, only provided that the prices of the commodities produced rise. Indeed, on this assumption the increase in output is associated— given the level of wages and prices of raw materials—with an increase in marginal costs which must be “covered” by the rise in prices. But higher prices of finished goods with given wage rates are tantamount to the fall in real wages which will thus accompany the expansion of output.

We have not taken into consideration so far a factor which will exert an additional pressure on real wages. We assumed the prices of raw materials to be given while in fact with the increase in production, and thus in the demand for raw materials, the prices of the latter will rise in accordance with the “law of increasing marginal costs”. This will affect the prices of finished goods additionally and as a result the reduction in real wages associated with the increase in production will be pro tanto greater.1

On the assumption of the “law of increasing marginal costs” production can increase with a given level of money wages only on the condition that prices rise and thus real wages decline. An increase in production may also ensue if the decline in real wages is the result of a cut in money wages while prices of manufactured goods are unaltered. The marginal costs of these goods at the initial level of output will fall (the curve of marginal costs will shift downwards), and this will encourage the entrepreneurs to expand production up to the point where the marginal cost is equal to the price.

Thus from the “law of increasing marginal costs” follows the inverse relation between production and real wages.

4. From this, however, it cannot be concluded that a reduction in money wages leads to an increase in production, since no relation between the changes in money and real wages has been established yet. The “classical” theory, in order to deal with this problem, makes additional assumptions of a different type. It is sometimes assumed that the general level of prices depends on the credit policy of the banks (in particular on that of the Central Bank). Assuming, moreover, that this policy, and thus the general level of prices, is given, the conclusion is arrived at that the reduction in money wages is identical with that of real wages.

Frequently, however, a more sophisticated assumption is made that it is the value of the aggregate demand or—what amounts to the same—the value of the aggregate production that is determined by the credit policy. Once we assume this value as given, the process of the reduction of money wages will be as follows. The cut in money wages results at the initial level of output in a reduction of marginal costs (the curve of which shifts downwards). However, the general price level does not change initially because the aggregate demand is assumed to be stable. Thus prices exceed the marginal costs, which leads to an increase in production. As a result the marginal costs increase and at the same time prices decline, since the same money demand is met by a larger volume of goods. The equilibrium is reached when the marginal costs are equal to the respective prices. This equilibrium is obviously reached at a higher level of production, and at a lower level of real wages than was the case in the initial position. Thus on the assumption of a given aggregate demand, a cut in money wages results in an increase in production accompanied, as follows from the above, by a reduction in real wages.

The assumption of a given general price level or a given aggregate demand is totally unfounded. We know only too well that in the course of the business cycle both magnitudes are subject to violent swings. Why then should we assume that they remain unaltered in the aftermath of a wage reduction? If, however, we reject these assumptions a quite new theoretical construction is required in order to enable us to appreciate the consequences of changes in money wages. We shall deal with this problem in the next section.

The Wage Reduction on the Assumption of Perfect Competition

1. In this section we assume for the time being rising marginal costs and perfect competition in accordance with the “classical” theory. We drop, however, the assumption of the stable general level of prices, or the stable money value of the aggregate demand. We shall assume in addition that the system is closed (we shall introduce foreign trade at a later stage), that it consists only of capitalists (entrepreneurs and rentiers) and workers, and that the workers do not save, but spend their total income on consumption. Before considering the consequences of a wage reduction within such a framework we have to advance some argument of a more general character.

2. The national income in our system may be presented in two ways, namely from the side of incomes and expenditure:

| Income | Expenditure | |

| Income of capitalists | Investment | |

| Wages | Consumption | |

| or | ||

| Income of capitalists | Investment | |

| Capitalists’ consumption | ||

| Wages | Workers’ consumption |

By investment is meant here the purchase of fixed capital (machinery, buildings etc.) and the increase in inventories. Since the workers are assumed to spend all their earnings on consumption, wages and salaries are equal to workers’ consumption. We thus obtain:

Capitalists’ income = Investment + Capitalists’ consumption

This equation is of fundamental importance for our subsequent argument. It enables us to explain the fluctuations of production. Let us consider investment, capitalists’ consumption and workers’ consumption in a certain period. In which of these three items of national income may spontaneous changes occur? It is first obvious that workers’ consumption cannot be subject to such a change. Indeed, it can neither exceed nor fall short of their earnings. But the position is quite different as far as capitalists’ expenditure is concerned. In the next period they may increase their consumption or their outlay on investment above their present income, drawing on bank credits or on reserves of their own. The capitalists also may reduce their expenditure on consumption and investment below their present income, paying off credits or increasing their reserves. Once they have done it, however, the above equation shows clearly that the income of the capitalists as a body will increase or diminish precisely by as much as their expenditure was increased or diminished. The aggregate production is bound to reach the level at which the profits derived from it by the capitalists are equal to their consumption and investment. Since the workers spend on consumption goods as much as they receive in wages, the remainder of the national income, being the share of capitalists, is just equal to their expenditure on consumption and investment goods. Therefore the capitalists as a class determine by their expenditure their profits and in consequence the aggregate production.

This result is likely to appear paradoxical to many readers. Therefore it will not be out of place to shed some light on it from a somewhat different angle.

We shall represent our system schematically as composed of three departments: production of investment goods, production of capitalists’ consumer goods and workers’ consumer goods or wage goods. The latter are partly consumed by workers who produce them, while the surplus is bought by the workers employed in the other two departments. This surplus is the profit derived from the production of wage goods. (Indeed, the value of the remainder is equal to the wages earned in this department). If for instance the value of the production of wage goods is 10 mld. zlotys and the workers employed in their production received 6 mld. zl. in wages, then the respective profits are 4 mld. zl. But as 6 mld. zl. earned in wages in the department of wage goods are spent on these goods, the surplus equal to 10 – 6 = 4 mld. zl. is bought by workers of the two other departments: the department of capitalists’ consumer goods and the department of investment goods. Thus the wages in the two departments as well as the profits in the third department are equal to 4 mld. zlotys. If employment and aggregate wages in the capitalists’ consumer goods and investment goods industries increase, the demand for wage goods increases as well and their production is bound to be stepped up to the point where the profits, i.e. the surplus of the value of production over wages in this department, would be equal to the increase of aggregate wages in the other two departments.

Next, the value of production of capitalists’ consumer goods and investment goods is, of course, equal to the sum of profits and wages in the corresponding departments. However, the wages in these two departments are equal to the profits in the third one; thus the total profits are equal to the value of capitalists’ consumption and investment. Let us suppose, for instance, that the value of production of these two categories is 7 mld. zl., out of which 3 mld. are profits and 4 mld. wages. As profits in the department of wage goods are equal to the wages in the other two departments, the former amount to 4 mld. Aggregate profits 3 + 4 = 7 mid. zl. are equal to the capitalists’ consumption and investment.

3. As will be seen, the fluctuations in production and profits depend on the fluctuations in capitalists’ consumption and investment. If at some moment, for instance, the entrepreneurs are in a more optimistic frame of mind, their investment activity will expand and employment in construction, machine industry etc. will increase. The resulting rise in the consumption of workers will in turn be followed by an increase in production of wage good industries. As was shown above, the aggregate production will expand to the point where profits will be higher by an amount equal to the value of additional investment—if it is assumed that capitalists’ consumption remains unchanged.

If, however, the latter increases as well, owing to higher capitalists’ incomes, the increase in profits will be correspondingly enhanced. In any case production will be finally pushed up to the point where the increase in profits will be equal to the increase in expenditure on investment and capitalists’ consumption.

The question is frequently asked about the “wherewithal” for financing the increase in investment if capitalists’ consumption does not decrease simultaneously and does not “release” some purchasing power for investment. It may sound paradoxical, but according to the above, investment is “financed by itself”.

If, for instance, an entrepreneur is gradually drawing on his bank deposit for construction of plat, he is increasing by the same amount (on the assumption of stable capitalists’ consumption) profits of other entrepreneurs (through an increase in the production), and as a result, along with the dwindling of his bank deposit the deposits of other entrepreneurs are rising pro tanto and therefore the banks are not forced to reduce credits. Here, however, an important reservation should be made: in line with the increased turnover the demand for cash in circulation rises. Consequently the bank deposits would diminish and thus the banks would lose a part of their cash reserves. This in its turn would cause an increase in the rate of interest which would adversely affect investment activity. For it is, indeed, the difference between the expected rate of profit and rate of interest that stimulates investment. However, the situation is relieved by the expansion of credits of the Central Bank which increases the quantity of money in circulation and in this way either prevents any rise in the rate of interest or at least limits its scope. One could, of course, envisage a banking policy which is designed to keep the aggregate demand at a constant level and, therefore, prevents production from either expanding or shrinking. (This is the assumption of the “classical” theory mentioned in the preceding chapter). In fact, however, the changes in the rate of interest are in general much too weak to halt an incipient upswing resulting from an increase in investment or to prevent a depression brought about by its collapse.

An important part is undoubtedly played here by a certain factor of a special nature. As we have just seen, an increase in the r...