- 306 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This title, first published in 1985, is the result of a cross-linguistic, comparative study of reflexives, with a major role played by syntactic conditions on reflexivization rules. The basic definitions outlined in the book lead to a discussion of morphological types, discussions about syntax, and speculations on the historical origins and destinies of the various kinds of reflexives. This title will be of interest to students of language and linguistics.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER I

What are Reflexives?

Before settling in to an examination of a phenomenon in many different languages, it is necessary to have some language-independent idea of what that phenomenon is, so that we know what to begin to look for. The tern reflexive must therefore be provided with some universal content. However, to give an airtight definition of the term at the outset would defeat the purpose of the whole investigation; we expect languages to differ amongst themselves in ways not predictable until the study is completed, and we hope to understand and explain these differences. Moreover, even within a single language the range of phenomena to be regarded as cases of reflexivization may be unclear. Consider, for example, the following English sentences:

(1) John saw himself in the mirror.

(2) John killed himself.

(3) John was pleased when a picture of himself appeared in the morning newspaper.

(4) This book was written by John and myself.

(5) John cooked supper by himself.

(6) John himself cooked supper.

(7) John cooked supper himself.

Obviously, reflexivization in English involves words like himself and myself, but are all of the sentences (1)–(7) to be considered cases of reflexives? In private discussions, sentences of all these types were suggested to me by various people as worthy objects of study in connec of the grammar of words like himself would indeed be interesting not only in itself, but for the light it would shed on the process of reflexivization in English at least, if not in language in general. On the other hand, the range of syntactic and semantic contexts illustrated in (1)–(7) cannot be used to define reflexivization universally, if only because, in contrast to English, other languages do not handle them in a uniform way. For example, .Japanese uses different patterns to translate (1) and (2).

(8) John wa kagami de zibun o mita

John TOP mirror LOC REFL ACC see+PAST

(9) John wa zisatu-sita.

John TOP commit-suicide+PAST

In (8), the reflexive pronoun zibun is used, but in (9) a special lexical item absorbs the reflexive. As another example, Russian uses different morphemes for the “emphatic” reflexive in (6) and for the object pronoun reflexive in (1):

(10) Džon uvidelsebja v zerkale.

John+NOM see+PERF+PAST REFL+ACC in mirror+PREP

(11) sam Džon prigotovil obed

“self” John+NOM prepare+PERF+PAST dinner+ACC

Conversely, there are contexts in which English uses an ordinary nonreflexive pronoun but another language will use what we will want to call a reflexive form. Such a case is the German sentence

(12) John sah eine Schlange neben sich/*ihm.

John see+PAST a snake near REFL/3MSG+DAT

which requires the use of the reflexive pronoun slch (the nonreflexive ihm is grammatical if it is not intended to be coreferent with John, of course) in contrast to the English equivalent:

(13) John saw a snake near him/?*himself.

which is most natural with a nonreflexive pronoun, even when that pronoun is intended to be coreferent with John.

We could of course just collect all the contexts that are handled by reflexives in at least one language and then claim that the universal process of reflexivization is defined by that set of contexts. Then we would say that in (13) English requires a nonreflexive pronoun for this particular reflexive context, or, that in Japanese, the reflexive is lexicalized in (9). However, in order to collect these reflexive contexts, we have to have a place to start. For example, how do we know that the German pronoun sich, whose required presence in (12) was interpreted as signalling a reflexive context, is in fact a reflexive pronoun?

My approach will be to give an archetypical reflexive context which can be examined in any language. This context will provide the starting point for deciding what grammatical devices will be considered reflexives in the language in question.

Specifically, I assume that, given any language, we can isolate a class of simple clauses expressing a two-argument predication, the arguments being a human agent or experiencer on the one hand and a patient on the other. Such clauses will consist of a verb, denoting the predicate, two noun phrases, referring to the arguments, and any tense-aspect, modal, agreement, or other grammatical material required by the syntax. (Of course, one or both of the noun phrases may be reduced to a pronoun or deleted entirely (depending on the language) if the reference is anaphoric, deictic, or unspecified.) Now, if the language has a grammatical device which specifically indicates that the agent/experiencer and the patient in such clauses are in fact the same referent,1 then that grammatical device will he called the primary reflexive strategy of that language.

Let us take English as a straightforward example, and, to keep things simple, consider only clauses with the main verb see, such as:

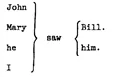

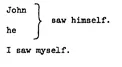

The subject and object noun phrases2 are coreferent if and only if the object noun phrase consists of one of the words myself, ourselves, yourself, yourselves, himself, herself, itself, oneself, or themselves. In traditional transformational grammar this has been described by saying that a rule of reflexivization changes the object noun phrase into the appropriate reflexive pronoun if it is coreferent with the subject.3 The presence of these reflexive pronouns in object position to mark coreference with the subject thus constitutes the primary reflexive strategy for English.

Just to illustrate a reflexive with a somewhat different surface appearance, let us look at some sentences in Lakhota, a Siouan SOV language:

| (16) | John thiobleca aeyokas’in. | “John peeked at the tent.” |

| (John tent peek-at) | ||

| John Mary aeyokas’in. | “John peeked at Mary.” | |

| John aeyomakas1 in. | “John peeked at me.” | |

| John aeyowakas’in. | “I peeked at John.” | |

| aeyomayakas’in. | “You peeked at me.” |

| (17) | John aeyoic’ikas’in. | “John peeked at himself.” |

| aeyomic’ikas’in. | “I peeked at myself.” |

In this language, non-third-person subject and object pronouns appear as prefixes or infixes on the verb. Several of these are illustrated in (16). However, just in case the subject and object referents are identical, an infix -ic’i- is inserted, together with a non-third-person pronoun, if necessary, as in (17). This reflexive infix is...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Table of Contents

- Chapter I: What are Reflexives?

- Chapter II: The Morphology of Reflexives

- Chapter III: The Syntax of Reflexives

- Chapter IV: How Reflexives Change

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Reflexivization by Leonard M. Faltz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Grammar & Punctuation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.