- 303 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Focus, Coherence and Emphasis

About this book

First published in 1984, this book examines a number of questions on the boundary of competence and performance — whose solutions have implications for linguistic theory in general. In particular, the form of grammatical statements, the relationship between various rules of grammar, the interaction between sentence in a sequence, and the inferences to be drawn from linguistic behaviour to linguistic knowledge. The author argues that many grammatical processes, inadequately handled by conventional sentence-grammars, require a text grammar in which the basic constitutive processes of information and deixis can be specified. They ago further to investigate the novel hypothesis that emphatic structure provides a crucial condition for the application of transformational rules, paying particular attention to the 'movement-rules' using mostly data culled from actual usage.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

Introduction: Bringing Things into Focus

1.1 The field of scrutiny

- 1.(a) Most people enjoy brandy after dinner(b) Most people ENJOY [brandy] after [dinner](c) [Brandy] is [enjoyed] by most people after dinner(d) It's BRANDY that [most] people [enjoy] after [dinner](e) What MOST people [enjoy] after [dinner] is BRANDY(f) [Brandy], most people enjoy after dinner

- 2.(a) *Have a brandy she DID(b) *JOHN, the FISH(c) *You'll find it BEHIND(d) *PUT it

- a. where there is a syntactic infelicity of some kind, that is, a sequence which cannot be generated in a standard grammar; examples include unorthodox word-orders such as (2a), and deviant complementisation as in (2c,d)

- b. where there is an information-gap of some kind: particularly the zero-anaphora type of example, as in (2b), but also to a lesser extent, the indeterminate pronoun, as in (2c,d). The latter type presents problems of interpretation rather than derivation.

- 3. (a) The Russians invaded Afghanistan - @Most people enjoy brandy after dinner(b) George enjoys malt whisky after dinner -@[Most] people ENJOY [brandy] after [dinner](c) What do people like to drink after dinner? - @[Brandy] is [enjoyed] by most people after dinner(d) Most people enjoy brandy with their breakfast- @It's BRANDY that [most] people [enjoy] after [dinner](e) Most people enjoy brandy with their breakfast - @What MOST people [enjoy] after [dinner] is BRANDY(f) Tell me about people's drinking habits here — @(Brandy], most people enjoy after dinner

- 4. (a) You know Mrs. Goldstein said she was going to have a brandy? Well, [have] a [brandy] she DID(b) George, you bring the soup. JOHN, the FISHor: George ordered the steak; JOHN, the FISH(c) Don't try looking for the artist's signature on the front of the painting. You'll [find] it BEHIND(d) Do you want me to throw the parcel on to the table or put it there? - PUT it

- 5. (a) Tell me about people's drinking habits here - Well, most people enjoy brandy after dinner

- (b) You don't have to FORCE that Remy Martin down you. After all, most people ENJOY [brandy] after [dinner](c) The brandy-producers have recently sponsored a market survey of their product. Apparently, [brandy] is [enjoyed] by most people after dinner(d) Really? I heard there'd been a change to VODKA - No, no: it's BRANDY that [most] people [enjoy] after [dinner](e) And I've also read somewhere that after dinner, cocoa is gaining in popularity. - Nevertheless, what MOST people [enjoy] after [dinner] is still BRANDY(f) Do Belgians drink a lot of brandy? —[Brandy], most people here [enjoy] after dinner

- 6. (a) The Russians invaded Afghanistan. They claimed to have been invited in by the regine(b) George enjoys malt whiskey after dinner. Most people [enjoy] BRANDY after [dinner](c) Most people enjoy brandy after dinner However, rising prices are preventing them from INDULGING in this luxury(d) Most people enjoy brandy with their breakfast- That's not true: what MOST people [have] with their [breakfast] is COFFEE(e) Most people enjoy brandy with their breakfast - No, it's DINNER that [most] people [enjoy] [brandy] with(f) Tell me about people's drinking habits here Most people enjoy brandy after dinner

- phonetic/phonological (e.g. stress, intonation)

- syntactic (structural variation)

- semantic (information-structure, reference, deixis)

- pragmatic (interaction, implicature).

1.2 A programme

1.21 What do we know about texts?

- - Sequences of utterances (and the sentence-sequences underlying them) are not simply random collections.

- - They display connections which are both syntactic and semantic-pragmatic in nature.

- - They occur in relation to practical situations.

1.22 What do we need to find out?

- - For sequentiality: how compatible is text -linguistics with sentence-linguistics?

- - For connectivity: what are the principles of sentence-connectedness; and what is the machinery of this relationship?

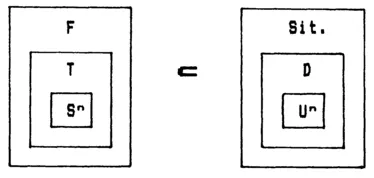

- - For contextuality: what are the principles and mechanisms of the text/frame interface?

1.3 Defining terms

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- List of Contents

- Dedication

- List of figures and table

- Preface and acknowledgment

- 1. INTRODUCTION: BRINGING THINGS INTO FOCUS

- 2. DISCOURSE

- 3. CONTEXT

- 4. CONNECTIVITY

- 5. THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS: SHARPENING THE FOCUS

- 6. EMPHASIS

- 7. CONTRAST

- 8. ANAPHORIC CONNECTIVITY

- 9. SYNTACTIC VARIATION: GETTING MOVEMENT INTO FOCUS

- 10. CONCLUSIONS

- BIBLIOGRAPHY AND AUTHOR-INDEX

- SUBJECT-INDEX

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app