![]()

A Reichenbachian Tense Logic

1.1 Introduction

The semantics of tense and other temporal expressions, involving as it does modification, recursion, contextual dependence, lexical variety, crucial scope relationships, and the interaction of elements in several grammatical categories is perhaps as rich and problematic as any in the field of natural language semantics. Model-theoretic semantics allows precise investigation using fairly simple mathematical techniques, and there is, finally, no lack of very competent work upon which to build. This is, in short, a most attractive field of study.

This work proposes a semantics for the description of temporal expressions inspired largely by Hans Reichenbach's brief remarks on the English tenses, and the insights of a number of contemporary researchers, including Partee (1973), Kuhn (1979), Baeuerle (1979), and Enc (1981), that tenses behave semantically rather like definitely referring (nominal) expressions. In spite of the attention paid to it, the parallel between tense and definite nominal reference, it is argued, has been insufficiently appreciated--both with respect to its extent, and with respect to its consequences.

The semantic theory presented in this first chapter is inspired by Reichenbach (1947), and it employs his three-way distinction among times relevant to semantic interpretation--the well-known speech, event and reference times introduced by Reichenbach. The semantics doesn't simply assume Reichenbach's system, but interprets it (and is somewhat selective about certain inexplicit aspects of his temporal descriptions). In the present interpretation speech, event, and reference times are viewed as times to which deictic reference may be made--effecting the parallelism to definite nominal reference mentioned above.

The proposed semantics is illustrated in Chapter 2 by an extended semantical sketch of German temporal reference. The proposed system for temporal semantics will be tested on an extensive, but necessarily limited range of temporal phenomena--including tense, temporal adverbials and particles, and the inherent temporal structure of verbs (Aktionsarten). All of these expressions are incorporated into a formal fragment (in Generalized Phrase Structure Grammar) in Chapter 3. Chapter 4 presents some semantico-syntactic extensions of the system developed in the first three chapters.

Ultimately, if it is to be adopted, the semantics proposed here must allow cogent analyses of all temporal reference, including not only the phenomena named above, but also temporal clauses, sequence of tense restrictions, and aspect. The system hasn't been tested on these phenomena to-date, though they do not seem to present special difficulties.

1.2 Triple Dependence

Reichenbach is to be credited for introducing the idea that the meaning of some tenses and temporal expressions depends not only on the time of speech, and the time at which an event takes place (or is reported to take place), but also on a third time, the reference time. In this chapter, I suggest a semantical formalization of Reichenbach's triple dependence and outline some further crucial background assumptions to a system using this formalization. Chapter 2 then argues that the semantics of temporal reference in German, in particular that of adverbs, and that of adverbial particles such as schon depends on the employment of reference time as a theoretical tool. (In the treatment proposed, reference time functions as one of three dimensions in a tense logic; it is otherwise the same concept introduced by Reichenbach.)

1.3 What is Reference Timeπ

The concept of reference time has puzzled some researchers. Reichenbach distinguished speech time s, event time e and reference time r. Let us examine these as Reichenbach applied them to the following example:

In 1678 the whole face of things had changed ... eighteen years of misgovernment had made the ... majority desirous to obtain security at any risk. The fury of their returning loyalty had spent itself in its first outbreak. In a very few months they had hanged and half-hanged, quartered and emboweled, enough to satisfy them. The Roundhead party seemed to be not merely overcome, but too much broken and scattered ever to rally again. Then commenced the reflux of public opinion. The nation began to find out to what a man it had entrusted without conditions all its dearest interests, on what a man it had lavished all its fondest affection. (Reichenbach, 1947:288f)

Speech and event time are easily recognizable. Speech time is simply the time of utterance (read here: writing), while the time of the various episodes described constitutes event time. As to reference time, let us note Reichenbach's remarks:

The point of reference is here the year 1678. Events of this year are related in the simple past, such as the commencing of the reflux of public opinion, and the beginning of the discovery concerning the character of the king. The events preceding this time point are given in the past perfect, such as the change in the face of things, the outbreaks of cruelty, the nation's trust in the king. (Reichenbach, 1947:289)

An event is thus seen not only from the vantage point of the speech time: it is also seen from time of reference.1) It is the time of reference which distinguishes the simple past from the past perfect. Each recounts episodes which are prior to speech time, but the episodes relayed in the past perfect are additionally prior to the time of reference. (We will accept Reichenbach's characterization of this distinction, and we try to provide additional support for it in principles for analyzing contextual dependence in 1.6.2.)

A reference time may be explicitly identified, e.g. as 1678 in the passage above, or it may be provided e.g. by a superordinate clause, as in the sentence below:

After he had eaten everything, he said good-bye.

'The event time of the subordinate clause is the time at which he ate. The reference time of this same clause is provided by the event time of the main clause: it is the time of his saying good-bye. Note that event time is prior to reference time here, and that the past perfect his used, just as it was in main cluases in Reichenbach's example. The configuration of speech, event and reference times is crucial, not syntactic structure. (Cf. 1.7.2.)

Reference time may be neither explicit nor provided by superordinate clauses, but given only by the context, as Reichenbach noted. He commented that in the sentence Peter had gone:

...it is not clear which time point is used as the point of reference. This determination is rather given by the context of speech. In a story, for instance, the series of events recounted determines the point of reference, which in this case is in the past, seen from the point of speech; some individual events lying outside this point are then referred, not directly to the point of speech, but to this point of reference determined by the story. (Reichenbach (1947:288))

Two aspects of Reichenbach's proposal will be exploited below. First, reference time is subject to pragmatic influence. Second, and more specifically, reference time may be given by the previous discourse.

Given this rough characterization of the notions of speech, event and reference times, we note that it was Reichenbach's strategy to ascribe one configuration of these times to each tense. For example, he lists the following (p.297):

| Past Perfect | E - R - S |

| Simple Past | R,E - S |

| Present Perfect | E - S,R |

| Present | S,E,R |

| Simple Future | S,R - E |

| Future Perfect | S - E - R |

E, R, and S stand for speech, event and reference times. A comma between two times stands for simultaneity, while the hyphen means that the left time temporally precedes the right.

Implicit in Reichenbach is surely the position that no more than three times are involved in the interpretations of any tense. I shall accept a slightly more general version of this position:

Maximally Triple Dependence: No more than three times are involved in the interpretation of any temporal expression.

The generalization is from "tense" to "temporal expression." The notion "times" is admittedly still vague above. It may be made precise in 1.4 through the notion "temporal index," and Maximally Triple Dependence will be seen to follow as a trivial consequence of the position that tense logic for natural language are three dimensional.

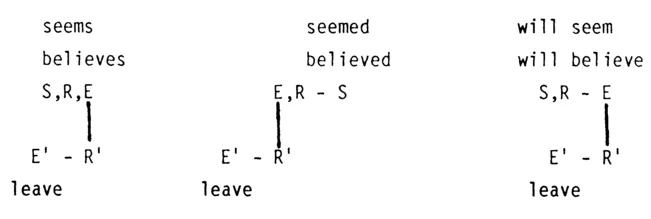

There is some reason, however, to reject other positions which also seem implicit in Reichenbach's analyses. Returning to the tense schemata above, it is perhaps remarkable that every tense specifies a linear configuration of all three times: in no case is a tense regarded as specifying a relation among less than three times, and never does it appear to have seemed necessary to Reichenbach to resort to nonlinear configurations of S, E, and R. On the contrary, however, the Perfect infinitive seems to require only that E precede R, and is indifferent to speech time, as the sentences below might suggest:

| He seems to have left | She believes him to have left |

| He seemed to have left | She believed him to have left |

| He will seem to have left | She'll believe him to have left |

This isn't the point at which one even could argue for any semantic rule in detail; we've simply developed too little of the overall apparatus for any rule to be justified in detail. But if we accepted Reichenbach's specification of the Present, Simple Past and Simple Future tenses (for the purposes of this illustration), then it might be seen that the only relationship with which the Perfect Infinitive may consistently be associated is that of the event time (of the VP to which it is attached) preceding reference time. The following schemata illustrate how the Perfect Infinitive specifies its times:

At least in the complements of the verbs seem and believe, the event time of the matrix clause is used as reference time in the complement. The Perfect Infinitive then marks the time at which the episode reported in the complement clause takes place--regardless of speech time.

The remarks above cannot be construed as defended analysis of the temporal import of the Perfect Infinitive--but only as an indication of the possible wisdom of allowing temporal elements to specify less than an exhaustive relation among speech, event, and reference times.

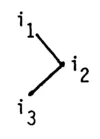

Similarly, there are tenses which seem to specify a nonlinear relation among the speech, event and reference times. This is perhaps a bit surprising. Relations are linear, of course, iff they are transitive, irreflexive, and connex. Clearly the points of time are ordered linearly under '<_,' so that it may be surprising that some tense specify times in a nonlinear fashion. The key is connexity. Recall that a relation R is connex in a set S iff

∀i1ϵS∨i2ϵS(i1Ri2 ∨ i2Ri1 ∨ i1=i2)

The connexity axiom disallows then situations such as the following:

where i...