![]()

1

Introduction

Constructing Narratives of (National) Identity within Relocations

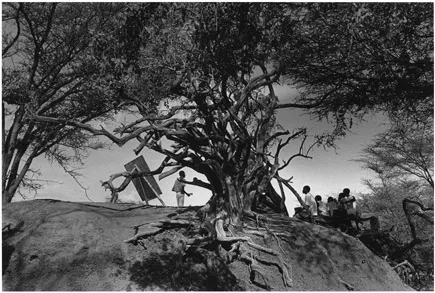

Figure 1.1 Boys learning from their teacher in a refugee camp in Kenya. © Sabastião Salgado. Courtesy of Contact Press Images.

Refugees and displaced persons, unlike migrants, are not dreaming of different lives. They are usually ordinary people—‘innocent civilians,’ in the language of diplomats—going about their lives as farmers or students or housewives until their fates are violently altered by repression or war. Suddenly, along with losing their homes, jobs, and perhaps even some loved ones, they are stripped even of their identity. They become people on the run, faces on television footage or photographs, numbers in refugee camps, long lines awaiting food handouts. It is a cruel contract: in exchange for survival, they must surrender their dignity.

Sebastião Salgado, Migrations: Humanity in Transition

The same is true of those who have been uprooted: once a refugee, always a refugee. He escapes from one place of exile, only to find himself in another: Nowhere is he at home. He never forgets the place he came from; his life is always provisional.

Elie Wiesel, The Time of the Uprooted

Frames of Displacement

Of the many photographs in Sebastiao Salgado’s Migrations: Humanity in Transition, there is one that stands out. Rather than the typical depiction of despair and hunger and tragedy, this photograph depicts boys learning. Spread across two pages, prominent in the picture is a large craggy tree with exposed roots that provides shade for a group of boys and their teacher. The teacher is standing in front of an easel, a striking technology in the midst of Salgado’s other photographs in the collection representing poverty, dust, and people living without shelter. Salgado’s frame provides an interesting narrative given the rest of his portfolio, which depicts mass migration in various locations in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. This photograph stands out in contrast to the written introduction to his book (cited above) where he notes that one’s dignity is often compromised in order to survive. In this photograph, the boys are not being objectified, at least not in the same way as the naked and starving children depicted in other photographs. On the one hand, Salgado’s collection of photographs could be said to recreate “the spectacle” of the trauma of forced migration (Hesford “Documenting Violations” 122) and reify our existing narratives about the hopelessness of the situation, thereby creating a distance between spectator and objects of the photograph. On the other hand, Salgado, like many attending to similar issues, is aware of this juxtaposition and asks, “Can we claim ‘compassion fatigue’ when we show no sign of consumption fatigue? Are we to do nothing in the face of the steady deterioration of our habitat, whether in cities or in nature? Are we to remain indifferent as the values of rich and poor countries alike deepen the divisions in our societies?” (14). The consumption fatigue to which Salgado refers is presumably the consumer culture of the west more generally—the consumption of brown or black bodies suffering malnutrition, war atrocities, and abandonment by their governments and international community. But as I explore in this book, the production and consumption of the displacement narrative by the west—including news reports of atrocities in refugee camps, published autobiographies of lost boys, photographs of lines of people walking across borders—are part of those narratives and feed into the very culture of consumption that Salgado critiques. His lone photograph of boys learning from their teacher in the midst of war and refugee camp living suggests there are other counter narratives worth exploring.

How we frame displacement matters. Displacement narratives do not merely reflect the material conditions of a person’s forced removal or dislocation. The narratives (or “frames,” as Butler would put it) are essential to the “perpetually crafted animus of that material reality” (Frames of War 26). That is, narratives drive the expected story and readers have narrative expectations of what happens in the displacement (or refugee) story. This book, therefore, creates “framing divisions” between local and transnational issues to explore connections between western expectations of displacement narratives and transnational productions of displacement narratives. Using historical, literary, ethnographic, and other cultural archives, this book provides a comparative rhetorical analysis of displacement narratives in the “frames” of the American imaginary.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), more than 67 million people were refugees or internally displaced persons either because of migration, natural disaster, or forcible removal. The sheer numbers of displaced persons and the complexities of social, economic, political, education, and personal issues related to these numbers have led scholars in a variety of disciplines to study factors impacting displaced populations. In disciplines such as rhetorical studies, literary studies, critical ethnic studies, refugee studies, cultural geography, and critical legal studies, among others, scholars are interested in the ways the displaced are represented and in the ways that refugees, migrants, and political dissidents interact with institutions of power. More particularly, scholars who examine these issues in relation to human rights discourses are interested in the ways that the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights has impacted representations of these groups and in turn how these groups represent their human rights-related stories (Hunt, Slaughter, McClennan, Moore, Becker and Werth, Bystrom, Coundouriotis and Goodlad, Guggenheim). Within rhetorical studies, only a few scholars address the rhetorical and narrative qualities of displacement stories (Hesford, Lyon, Lyon and Olson, Bohmer and Shuman, Bystrom, Becker and Werth), attending primarily to human rights issues within specific displacement events. This book extends their work by examining more than one displacement moment at a time. I examine what I call “layered displacements” to account for the rhetorical and narrative qualities of displacement stories across events.

In order to explore narratives of displacement, then, I discuss three different types of displacement in three very different geographical locations. I begin with the United States, examining several eminent domain cases and Hurricane Katrina. I then turn to two different transnational cases—the civil war in Sudan, and the tsunami and civil war in Sri Lanka—to understand the ways the west’s expectations of displacement narratives influence the way these texts are read. At first glance, it may seem a major leap to move from several groups of Americans losing their homes to conservation development, natural disaster, and eminent domain to vastly different groups from different national, cultural, and linguistic traditions. However, examining legal, political, and individual narratives from places whose histories are intricately intertwined with American understandings of displacement reveals the systematic and routine ways that American discourses of eminent domain intersect with transnational discourses of resettlement, civil unrest, and natural disaster. Identity and Power in Narratives of Displacement shows how notions of human rights and the “public good” are often at odds with individual well-being and result in powerful intersections between discourses of power and discourses of identity. Indeed, it is precisely the seemingly disparate nature of the case studies that makes their similarities intriguing from a rhetorical point of view. Given the ever-increasing numbers of displaced persons across the globe, this study sheds light on the resources of rhetoric as means of survival and resistance during the globally common experience of displacement. This book brings together these seemingly disparate events and locations by focusing on the rhetorical strategies similar in each that point to normative discourses operating across events. As a study that contributes rhetorical understanding to the existing literature on the experiences of displacement, these case studies reveal the interesting ways that displacement narratives function within, among, and across disparate events and yet speak back to normative discourses in critical ways.

Methodologies: Limits, Interiority, and Revealing Contemplations

The existing literature relevant to this topic is vast: studies of the refugee, the diaspora, exiles, migrants, and asylum seekers are all pertinent to the discussions in this book. Indeed much of the scholarship in these areas has been critical to my understanding of what it means to be a displaced person. Therefore, I create here an integrative approach, one that draws on relevant studies, but also one that takes up multiple displacement narratives from a rhetorical point of view. Throughout the chapters, whether discussing U.S., Sudanese, or Sri Lankan narratives, I examine the rhetorical similarities among them, and point to the ways some resist accepted constructions of displacement. Informed by “situated individual identity articulations” (Blommeart), “moving bodies” (Hawhee), and “scattered hegemonies” (Grewal and Kaplan), this project challenges our understanding of rhetorical renderings of moving identities. To do this I combine autobiography, genre, narrative, and displacement theories to speak to works across disciplines that have discussed displacement from cultural anthropological, psycho-social, and geographical perspectives.1 The social and psychological dimensions of refugee and migration experiences have exploded in postcolonial and feminist studies. However, issues of representation and the limits of language in representing these social phenomena are relatively unexamined from a rhetorical point of view. I therefore use a transdisciplinary and transnational approach, informed by feminist and queer epistemologies of abjection and vulnerability, to bring these discourses together.

This mixture of methodologies is also informed by feminist rhetorical practices. Primarily I use narrative and rhetorical analytical methods, with the assumption that rhetoric is “an embodied social experience” (Royster and Kirsch 131). As a result, the narratives discussed in this book are examined for the material contexts in which people put pen or pencil to paper, or fingers to keyboards, or speak into microphones. By doing so, I create an integrative framework of interpreting human rights discourses and formulate a new analytical paradigm for understanding the ways that human rights are configured rhetorically across a spread of historical and geographical locations. This transnational, feminist approach seeks to span and link timeframes and seemingly disparate events to determine if and how rhetoric functions across these varied material contexts. This framework also works from the assumption that “the rhetoric of narrative is inextricably bound to cultures out of which particular narratives are constructed” (Journet et al. 4) is are ethically and ideologically charged (Phelan).

As an embodied social experience steeped in ideology, then, narratives of identity are linked to narratives of power with social constructions of subjectivity (Foucault). As “creative means of exploring and describing realities” (Andrews et. al.),2 narratives are also temporal (Ricoeur) and reflect the socially situated, materially contextual moment in which the narrative was written or spoken. Representations of identities within those narratives, then, are “always producing [themselves] through the combined processes of being and becoming” (Yuval-Davis 201). In order to examine displacement narratives that challenge dominant narratives of displaced individuals, I follow the lead of scholars such as Joseph Slaughter in Human Rights, Inc. and Elizabeth Anker in Fictions of Dignity, who place narrative as a central way of examining human rights, migration, and refugee law. In addition, I place genres alongside one another to examine transnational influences of displacement narratives, creating a “pastiche of methodologies” (Kaplan 6) to highlight the ways that representation, cultural production, and framing are crucial components of moving identities. In this way I hope to challenge the ways we understand displacement narratives, and in turn inform our understanding of the material functionality of eminent domain, condemnation, and resettlement laws. I work toward using the principles of “diffractive methodology” (Barad 88) to underscore the labeling distinctions on one place over another and the limits and gains of doing so, together with Royster and Kirsch’s notion of strategic contemplation, to keep at the forefront the social and personal systems at work in interpretation. The analyses in this book, therefore, take all these issues into account, not attempting to occupy or discover what is in the texts (Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies), but rather to expose systems of order and power and to reveal and understand the processes of constructing identities within them.

Of the many examples of displacement available for analysis, I choose these specific eminent domain, natural disaster, and civil unrest cases because of the ways that readers have interacted both with media representations of the events and with the ways that their international contexts inform our understanding of national contexts. I therefore examine multiple kinds of texts, including documentary film, media coverage, oral histories, legislation, refugee intake interviews, novels, and memoirs, attending to the ways genre expectations merge with identity representations. These seemingly different contexts and genres are placed together because of their emphasis on individual stories, their connections to human rights discourses, and the questions of invention and rhetorical construction that each raise.

By examining multiple kinds of displacement at once, Identity and Power in Narratives of Displacement interrogates western audiences’ conceptions of what constitutes a legitimate displacement narrative. I therefore begin with cases in the United States, examining several eminent domain cases and Hurricane Katrina’s residual resettlement and rebuilding laws. Understanding the United States’ history with displacement, particularly its laws regulating land use and citizenry, reveals an emergent pattern in displacement narratives as the displaced speak back to institutions of power. With explication of several significant eminent domain cases, such as the formation of Shenandoah National Park in Virginia and the intersections of natural disaster and eminent domain law in New...