![]()

1 Opening

Protesting the Results

In the days immediately following the June 12, 2009 Iranian presidential election, in which the incumbent Mahmoud Ahmadinejad won by a controversial landslide victory over the reformist candidate Mir-Hossein Mousavi, protests erupted in Tehran over alleged vote-rigging and election irregularities.1 Although initially peaceful, these demonstrations quickly turned violent as clashes broke out between police and protesters, leading to numerous arrests and casualties. With the protests intensifying, the headlines on reports coming out of Tehran from major U.S. or global news outlets might have read: Tehran Erupts in Protest or Shades of ’79 as Demonstrators Challenge Contested Election Results. Accompanying those reports would have been global press agency images of amassing demonstrators clad in green and their clashes in the streets with police and Basij paramilitary forces. Others might have captured the bloodied faces of protesters, some of them young women in headscarves, perhaps a few burning Basiji trucks. Global media outlets’ televised news broadcasts and online reports on the Iranian protests might have featured satellite video framed by standup reports from on-the-scene reporters soundtracked with protesters’ chants and backdropped crowds amassing in Tehran’s Azadi [Freedom] Square.

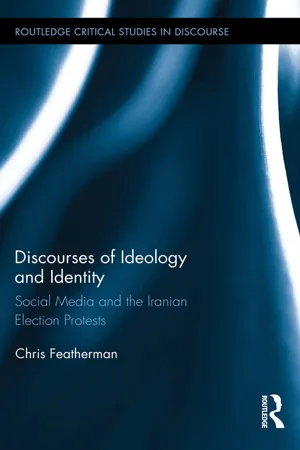

But in the early stages of the 2009 Iranian presidential election protests, which would come to captivate a global audience and arguably presage the Arab Spring of 2011, those headlines, images, and videos did not readily appear. Following a tense election run-up, the Iranian government banned foreign media, and when the protests broke out, they instituted a communication blockade to prevent news of the protests from being disseminated outside the country. But Iranian activists using web-based social media eluded the government censors, and some of the first reports of the crisis to reach a global audience were tweets, or posts, such as the one shown in Figure 1.1, to the microblogging service Twitter.

With a cultural status rivaling that of the social networking service Face-book and its ubiquitous embedding in legacy online news media, Twitter is now a popularly well-known form of social media.2 A microblogging service, Twitter allows users to write and share with followers posts of 140 characters or less. Because of its brevity, Twitter is especially suited to use on mobile devices, such as smartphones, whose availability and popularity, at least for the global elite, have paralleled Twitter’s spectacular growth.3 Since being launched for public use, Twitter has grown from approximately 1,000 active accounts in 2006 to more than 255,000,000 as of June 2014.4 Prior to 2009, however, Twitter, in all its brevity, was widely seen as little more than a regularly updated commentary on users’ everyday lives, with some early critics calling it ‘fatuous’ and ‘banal’ while dismissing its value as an application (Arceneaux & Schmitz Weiss, 2010). Even as Twitter gained more popularity (primarily through its adoption by young entertainment celebrities and professional athletes), many, including the mainstream legacy press, continued to view it skeptically. As with the advent of text messaging, or Short Message Service (SMS), some critics even suggested that Twitter’s constraints would negatively influence the trajectory of language change and, like other forms of social media, prove harmful to young people’s communicative practices (Thurlow, 2006).

Figure 1.1 Iranian activist’s tweet from the 2009 protests.

By the time of the 2009 Iranian presidential election protests, however, Twitter had not only grown exponentially; it had also begun to shed some of these negative cultural perceptions, surpassing what Grewal (2008) has called the threshold of visibility, or the point when a network grows large enough to appeal to what had been non-users. As numerous mainstream journalists began to recognize the advantages of microblogging’s instantaneous updates through mobile phones, the adoption and use of Twitter by legacy media reporters helped reshape news gathering and distribution. Twitter also started playing a notable role in political elections, including the 2008 U.S. presidential contest, in which, on election night, before appearing on national television, Barack Obama famously announced victory on Twitter to the hundreds of thousands of followers he had acquired during his campaign.5 And arguably presaging its use by Iranian activists during the June 2009 crisis, Twitter had become a critical tool for communication and organization during political protests, including the civil unrest that gripped Moldova in April 2009 (Miller, 2010; Morozov, 2011).

When news, then, of the Iranian election crisis broke, reports that activists were using Twitter and other forms of social media became part of the news frame. Seizing this kairotic moment in full, prominent blogger Andrew Sullivan (2009), then writing on June 13 for The Atlantic, quickly dubbed the movement ‘The Twitter Revolution,’ citing the microblogging service as “a critical tool for organizing resistance” (n.p.). Although most mainstream news reports rejected Sullivan’s epithet as cliché, they did extend the election news frame to accommodate the social media micronarrative and consider its possible relevance within the context of the election crisis. A series of reports in legacy media outlets in the United States, including the Washington Post and the New York Times, examined the role of web-based new media in both the election campaigns and the protests that followed. In his book The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of the Internet, Evgeny Morozov (2011) has countered Sullivan’s—and many others’—moment of jubilant cyber-utopianism, along with the somewhat more tepid conjecture in the initial legacy media reports, with a strong dose of skepticism about the potentially liberatory and democracy-promoting capabilities of social media which, coincidentally, happen to originate in the U.S., arguing:

the irrational exuberance that marked the Western interpretation of what was happening in Iran suggests that the green-clad youngsters tweeting in the name of freedom nicely fit into preexisting mental schema that left little room for nuanced interpretation, let alone skepticism about the actual role that the internet played at the time. (p. 5)

For Morozov, these interpretations reflected both a triumphalism and sense of Western superiority that has existed since the fall of communism in 1989. Viewed from perhaps an even wider perspective, we might also see how they index the ways in which globalization, power, knowledge, and ideology are caught up in what Mittelman (2004) has called a vortex of struggle. In that struggle, I argue, we can see the contingent links between knowledge and political conditions—particularly, in this case, the discourses of democracy and cyber-rhetoric together with those of modernity and tradition that have shaped Western perspectives of Iran and other Islamic countries (Rajaee, 2007). At the nexus of these discourses are, among other notions, ideology, identity, and the ways in which social actors can generate both communication power and counterpower, particularly in relation to language and technology.

Twitter was not the only social media service that activists and social movement participants used to coordinate and document collective actions. Photo- and video-sharing services, such as Flickr and YouTube, were also used to disseminate, respectively, images and video clips, often taken with mobile phone cameras and shared through mobile applications. Networks of activists and followers could then share these images—frequently using hyperlinks embedded in tweets and SMSs—to circulate images such as those in Figures 1.2 and 1.3. Doing so not only helped elude government censorship and spread news of the crisis beyond Iran’s borders, but it arguably also helped expand the social movement across new nodes, or connection points in a network, which can create new possibilities for collective action.

Figure 1.2 Mass demonstration in Azadi Square, June 15, 2009.

Discursive practices such as these show the important role of mobile technologies in facilitating the circulation of news and information. They also highlight the ubiquitous, linguistic, and increasingly mobile and visual character of the Internet and information and communication technologies (ICTs) in contemporary society, although predominantly for the global elite (Crack, 2008; Norris, 2001). As part of the mobile turn in communication, such practices have also helped shape the everyday production of culture (Caron & Caronia, 2007). With language infused in this complex and mobile fabric of relations (Urry, 2010), Internet-based mobile communications, particularly social media, have helped further liberate users from many of the temporal and spatial constraints that govern their lives (Giddens, 1991). Across global networks, transcultural flows of images and information cross borders nearly instantaneously, bringing distant places in contact and helping form sociomental bonds and translocal loyalties across borders (Chayko, 2002). As a result, it is argued that social relations become disembedded, or lifted out, from their contexts and restructured across spans of time-space, producing a rescaling of social activity that can work to enact forms of identity in discourse (Benwell & Stokoe, 2006; Castells, 1997; Fairclough, 2006; Giddens, 1990). The resulting deterritorialization can decouple community from place, removing the primacy of locality in sociocultural meaning and allowing, through collective imagination, social life to be a site for multiple, coexisting worlds (Albrow, 1997; Appadurai, 1996). As a dialectical phenomenon, however, this interlacing of social relations at a distance with local contexts also allows for the competing interpenetration of contexts (Robertson, 1995), novel forms of localization and global identification (Pennycook, 2007), and the mobility of sociolinguistic resources of indexical distinction across scale levels (Blommaert, 2010).

Figure 1.3 Cellphone video capture uploaded to YouTube.

Yet, despite this capacity to restructure social links and events and reformulate possible meanings, global technologies should not be viewed through the lenses of technological determinism at the expense of other processes (Chadwick, 2006; Hopper, 2007). As sociologist Manuel Castells (2009) has explained, “network technology and networking organization are only means to enact the trends inscribed in social structure” (p. 24). To examine, then, the effect of instantaneous communicability over space on language practices, we should draw our attention not strictly to networks and ICTs, but to the novel and diverse spaces which have opened up within global networks (Harvey, 1989). Across these sets of interconnected nodes, in which information, more than capital or labor, is the vital source of value, identifications become social actors’ primary source of meaning (Castells, 1996, 2000). And in a network society, communication is a source of both power and counterpower (Castells, 2009). In the view that power is not absolute but negotiated, the struggle for power today is ultimately the battle to control minds, the struggle over the way people think (Castells, 2010). With respect to the media, this means, as has been widely argued through the critical studies of legacy news media discourse, that both national and global media outlets have a hegemonic power to confirm ideologies. But when used tactically, ICTs and social media can grant social actors a form of counterpower, a capacity to challenge dominant ideologies and resist institutional control over the flow of information (Castells, 2009; Renzi, 2008). And it is in the context of these dynamic processes that I explore, in this project, the way that ideologies and identities can be discursively constructed, in both ‘old’ and ‘new’ media and during times of crises such as the 2009 Iranian election protests.

Contexts: Globalization and New Media as Frameworks for Sociolinguistic Research

The complex, multifarious, and intrinsic connections between language and the processes of globalization have been well established in recent sociological and sociolinguistic research (Block & Cameron, 2002; Blommaert, 2010; Giddens, 1990; Tomlinson, 1999). So, too, has been the analysis of legacy news media discourse, including its roles in the construction of ideologies (Fowler, 1979, 1991), the establishing of sociopolitical agendas (Fairclough, 1995), the production of cultural identifications (Hall, 1996), the geopolitics of representations (Mody, 2010), and the global cultural flows disseminated through ICTs (Appadurai, 1996; Castells, 2000). Also well established i...