- 282 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Return Migration and Regional Economic Problems

About this book

This book, originally published in 1986, based on extensive original research, presents many findings on the phenomenon of return migration and on its impact on regional economic development. It remains the only study of its kind. International in scope, the book includes chapters on return migration in Italy, Portugal, Greece, Ireland, Jordan, Canada, Jamaica, Algeria and the Middle East.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 RETURN MIGRATION AND REGIONAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT: AN OVERVIEW1

DOI: 10.4324/9781315722306-1

INTRODUCTION: THE DEVELOPMENT OF RETURN MIGRATION LITERATURE

Before the 1960s the literature on migration made little or no reference to the phenomenon of return migration. If return migration was mentioned it was only to lament that so little material existed on it. It is true that Ravenstein, father-figure of migration studies, mentioned ‘counterstreams’ in both of his seminar papers published one hundred years ago (Ravenstein, 1885, p. 187; 1889, p. 387), but there was some confusion over whether the counterflows were mainly returnees or flows of migrants merely moving in the opposite direction to the dominant stream. Neither was this point clarified by Lee (1966) in his reformulation of Ravenstein’s ‘laws’ 80 years later. One indication of the lack of attention paid to return migration by the late 1960s is the extensive migration bibliography compiled by Mangalam (1968) which, in more than 2,000 entries, lists only 10 references on return migration.

The reasons for this lack of acknowledgement of return migration are not hard to see. Return migration has always been one of the more shadowy features of the migration process, principally because of the difficulty of obtaining satisfactory data for this phenomenon. The nets cast out in migration surveys and national censuses usually allow return migration to slip through. It was, therefore, not surprising, though not entirely excusable, that so many studies of migration proceeded as if no returns ever took place.

But return migration’s statistical elusiveness is not the whole story. In explaining the reluctance to come to terms with return migration, there is a lot to be found in the nature of traditional frameworks for analysis used by migration researchers, and in particular in the strong and entrenched ‘rural-urban’ framework (Rhoades, 1979). So often, migration is portrayed as a one-way process that starts in the countryside and terminates in the city. This, and the particular locational and disciplinary perspective of the individual researcher, has influenced the types of migration analyses that have been most common. Prior to the recent interest in returns, three major foci could be identified for migration research. Firstly there were studies of the initial migration decision. These ranged from sometimes highly abstract economic and mathematical models to more individually-focussed behavioural studies, and of course also included the familiar ‘push-pull’ rationales. Second, there have been quite literally thousands of studies of migrant adaptation, assimilation, acculturation, integration (call it what you will) and of migrant-non migrant interaction in the receiving society – nearly always an urban centre. Thirdly, some social scientists have examined the consequences of emigration for the sending communities and regions; these have tended to look at the direct, immediate effects of out-migration, not the impact of returns. These three topics have nearly always been dealt with in isolation from each other. Rarely have they been examined in terms of any systematic whole to which they are all related and in which return migration plays a part.

Amongst the very few major studies of return migration prior to 1965, pride of place must go to Theodore Saloutos’ pioneering study of Greeks returning from the United States – a sensitive and sometimes humorous description of a group of migrants who returned after more than half a lifetime across the Atlantic (Saloutos, 1956). Another important, but lesser-known, early study is the account by Useem and Useem (1955) of the return of the ‘Western-educated man’ to India.

The ‘take-off’ period for the return migration literature was the 1960s when a number of studies appeared under three general areas. The first of these concerned further analyses in the context of the United States’ main suppliers of migrant labour at that time: Italy (Cerase, 1967; Gilkey, 1967; Lopreato, 1967), Puerto Rico (Hernández Alvarez, 1967; Myers and Masnick, 1968) and Mexico (Form and Rivera, 1958; Hernández Alvarez, 1966). The second were the studies of British return migration from Australia (Appleyard, 1962; Richardson, 1968) and Canada (Richmond, 1966 and 1968). The third were the studies of return migration from Britain to the West Indies (Davidson, 1969; Patterson, 1968; Philpott, 1968). The major landmark study of this period was the monograph by Hernández Alvarez (1967) on return migration to Puerto Rico. Like Saloutos’ book it was a model of its type and was much referred to in research published in the ensuing few years.

The flow of return migration literature swelled further in the early 1970s, and it is tempting to suggest that this was due to the onset of world-wide recession which, especially in the West European arena, provoked sudden and marked turnabouts in migratory trends. The threshold of 1973/4 was when countries like France and West Germany stopped admitting large numbers of migrants and pressures mounted for repatriation and return (Kayser, 1977; Lebon and Falchi, 1980; Lohrmann, 1976; Slater, 1979). The last ten years have therefore seen a steady flow of return migration studies, many based on empirical research. This introductory chapter is not an appropriate place to make reference in any complete sense to this work – for a fuller bibliographic listing the reader is referred to King and Strachan (1983). Instead I shall concentrate on the concepts and research findings that refer specifically to regional economic issues.

SOME DEFINITIONS

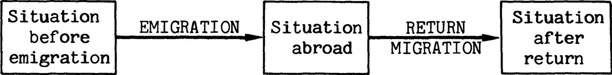

Whilst not wishing to get embroiled in a detailed discussion of the definition and types of migration – a topic of potentially endless debate – it is clear that we must define exactly what is meant by return migration. This is necessary because there is much terminological sloppiness in the return migration literature. The simple schema on Figure 1.1 places return migration in the context of the migratory cycle, which consists of three static stages linked by migration moves out and back. This introductory review is concerned primarily with the last two elements of the schema, viz. the return move itself, and the post-return situation. However, inasmuch as return migration is often largely conditioned by earlier steps in the migration cycle, these are occasionally referred to as well.

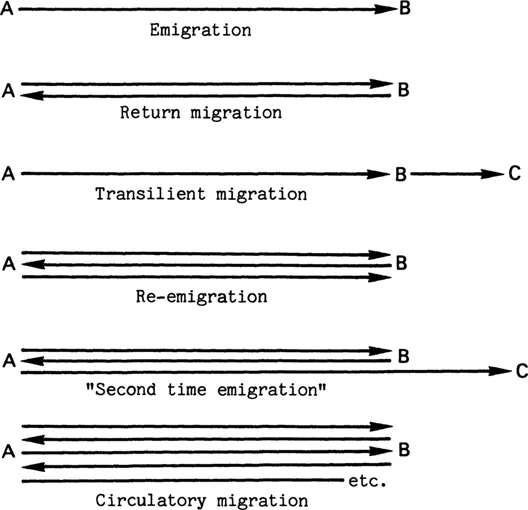

Figure 1.1 is also an oversimplification in that it does not admit a whole range of other possibilities that might stem from an original migration move. Figure 1.2 looks at a range of possible migration paths that could result from an initial emigration. Note that Figure 1.2 portrays the case of international migration – hence the use of the term emigration – but it can easily be applied to internal migratory moves within a single country.

Following Figure 1.2 the following terms can be defined. Return migration is used when people return to their country or region of origin after a significant period abroad or in another region. When people move directly from the first destination B to a second destination C without returning to their home area A, as, for example, an Italian migrant transferring from France to Germany (as many did in the 1960s), then this is termed transilient migration. When people emigrate once again to the same destination B after having returned for the first time, we can call this re-emigration; but when people emigrate to a new destination C after having returned from B, this is termed second-time emigration. When the to-and-fro movements become repetitious, we term this circular migration which may become seasonal migration if the movements are regular, dictated perhaps by climate or the seasonal availability of certain types of work (harvesting, construction in cold climates, holiday industry employment etc.). The term repatriation is used when return is not the initiative of the migrants themselves but is forced on them by political events and authorities, or perhaps by some personal or natural disaster.

TYPES OF RETURN MIGRATION

Just as migration is a highly multifarious phenomenon, return migration too comprises a range of different types. A preliminary typology can be identified with regard to the differing levels of development of the countries involved (King, 1978, p. 175). Three cases may be envisaged. Firstly, there are movements of people between countries of roughly equal standards of living and levels of economic development, but with varying demands and opportunities for labour (e.g. British migration to and from North America and Australia). A second type involves movements of ‘developed country’ migrants back from less developed, often colonial or former colonial territories (e.g. French from Algeria, Belgians from the Congo, British from Kenya, Portuguese from Angola, etc.). The third situation, and numerically by far the most important, is the return migration of workers and their families from the more developed industrial countries to the labour-supply countries (e.g. West Indians from Britain, Puerto Ricans from the USA, Turks from West Germany, etc).

Aside from this ‘developmental’ typology, there are many other types of return migration which need to be mentioned. These ‘marginal’ types of return movement include ‘pilgrimage migration’, circular migration and what may be called ‘ancestral return migration’. Pilgrimage migration is most notable in the case of the haj or pilgrimage to Mecca. Pilgrims heading for Mecca from the countries of West and Sahelian Africa take an average of eight years to complete the journey: five out and three back (Birks, 1975, p. 299). Returning West African pilgrims are a prominent feature of the agricultural labour force of the Sudan (Davies, 1964). Circular migration is also predominantly African. Although circular movement by definition embraces repeated returns, these are often not identified as an object of separate study: hence the marginality of circular migration to a study of return migration. The circular migration of African wage labourers between their villages of origin and their places of work in the towns is normally a domestic movement which takes place within a single culture area (Gmelch, 1980). Although there are obvious differences between life in the villages and urban society and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1. RETURN MIGRATION AND REGIONAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT: AN OVERVIEW

- 2. GASTARBEITER GO HOME: RETURN MIGRATION AND ECONOMIC CHANGE IN THE ITALIAN MEZZOGIORNO

- 3. THE OCCUPATIONAL RESETTLEMENT OF RETURNING MIGRANTS AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT: THE CASE OF FRIULI-VENEZIA GIULIA, ITALY

- 4. LAND TENURE, RETURN MIGRATION AND RURAL CHANGE IN THE ITALIAN PROVINCE OF CHIETI

- 5. THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF RETURN MIGRATION IN CENTRAL PORTUGAL

- 6. RETURN MIGRATION AND REGIONAL CHARACTERISTICS: THE CASE OF GREECE

- 7. THE READJUSTMENT OF RETURN MIGRANTS IN WESTERN IRELAND

- 8. RETURN MIGRATION AND URBAN CHANGE: A JORDANIAN CASE STUDY

- 9. THE IMPACT OF RETURN MIGRATION IN RURAL NEWFOUNDLAND

- 10. IMPLICATIONS OF RETURN MIGRATION FROM THE UNITED KINGDOM FOR URBAN EMPLOYMENT IN KINGSTON, JAMAICA

- 11. RETURN MIGRATION TO ALGERIA: THE IMPACT OF STATE INTERVENTION

- 12. BRIDGING THE GULF: THE ECONOMIC SIGNIFICANCE OF SOUTH ASIAN MIGRATION TO AND FROM THE MIDDLE EAST

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Return Migration and Regional Economic Problems by Russell King in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.