![]()

Part 1

The economy and economic geography

In this section we present a simple model of the economy around which the rest of the book is constructed. The model also serves to indicate certain themes and issues arising from the geographical study of economies and these are considered against the background of a selection of the diverse literature in the field of economic geography.

![]()

In this book the term ‘economy’ refers to a network of economic decision makers. Such a mechanistic interpretation derives from neoclassical economics as the major source of theory in economic geography. This dependence is misplaced as neo-classical economics hides the fundamental structural relationships between people in the social production of material life beneath its concern with the exchange of commodities considered merely as material objects. However just as economics is breaking free from its neo-classical strait-jacket so too should economic geography. The speed with which it does this is an important determinant of the rate of obsolescence of this book.

Underlying the argument pursued in these pages then, is the neoclassical concept of the economy which, so it seems to us, can only be fully understood when treated as a whole. But economies, as defined here, can exist at any scale. They range from simple subsistence village economies through to those operating at the national or international scale. Yet even at its simplest the economy is a complex phenomenon. The reader may find it useful to consult some of the descriptive case studies of simple village economies written by economists, social anthropologists and geographers (e.g. Firth 1952; Epstein 1962; and Hill 1972). It is not possible to translate their findings from one spatial scale to another, but such studies are useful in that they introduce the concept of the economy by describing, within the context of a small and specific community area, the complex integrated and continually changing interaction of variables affecting economic activity. In this book, however, the approach is to try to simplify the characteristics and operation of economies, at whatever scale, down to common elements and processes. We begin by setting up a very simple model of the economy.

A simple model of the economy

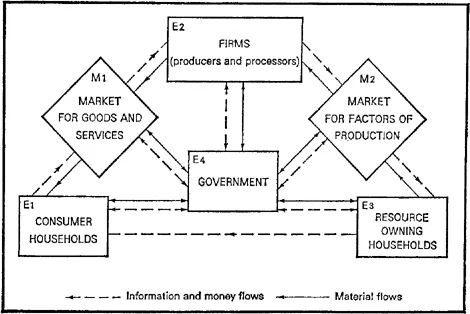

The economy, as revealed in fig. 1.1, may be said to consist of:

1. A set of decision-making elements identified as consumers (E1); firms (E2), often grouped into particular industries or sectors; resource owners (E3); and government (E4).

2. A set of relationships between the elements, shown in fig. 1.1 by the dashed and continuous arrows connecting them, facilitated by the market for goods and services (M1) and the market for factors of production (M2).

3. A set of relationships between these components and the total environment, which may be simply defined as a higher order system within which the economy, or economic system, is but a part.

In this sense economic activity can be said to consist of the actions and interactions of four sets of elements. For a variety of reasons, the most basic of which is self-preservation, consumers (usually measured as consumer-households) generate wants and needs or demands for goods and services. Firms, or the technical and organizational units for production and processing, may respond to this demand by deciding to produce the goods demanded. To do this they need to acquire the resources of land, labour and capital from resource owners (resource-owning households). In other words, firms may generate a demand for resources and may try to attract them by the offer of some form of payment to the owners of the resources. If this offer is satisfactory the resource owners may decide to release at least some of their resources. Firms can then generate productive services (or factors of production) from the input of resources which are used in combination to make goods by the process known as production. The goods, or output produced by firms, can then be offered to the consumers. If the latter are satisfied with the goods and decide to accept them, then the firms receive a return, or payment, in exchange for the utility of the goods. In reality, all economically active households in the economy are both consumers and resource owners; the payment, or income, received from firms by resource owners may in turn be used to purchase goods from firms by the same individuals in their role as consumers. Transfer payments are made via government to those households unable, for reasons of old age, ill health or unemployment, to be economically active; such payments are supposed to enable these households to behave as consumers.

Firms are linked to consumers and resource owners along a network of communications via the market for goods and services and the market for factors of production. A market is a process of communication that enables buyers and sellers to exchange information about actual or latent demands and available or potential supplies, and helps them to organize the sale and purchase of goods and services. This type of activity may take place within well-defined market places which act as commercial foci for buyers and sellers and so are referred to as central places. But not all commodities and information are exchanged at a central place. The market for iron ore, for example, has no places of exchange at which buyers are able to meet and draw upon supplies from a particular market-supply area. Furthermore, the reduction in ore transportation costs is causing formerly discrete supply areas to coalesce, so that any one supplier of iron ore may well serve buyers in spatially separate locations (Manners 1971a). Sometimes the term market is used in a less specific context to include all the intermediate and final destinations of goods or resources being exchanged between buyers and sellers. In chapter 8 we shall devote more attention to the study of market places but our present interest in markets is as the means by which information and goods are exchanged within economies.

This description of economic activity assumes that it is set in motion and controlled by decentralized decision makers whose activities are stimulated by the likelihood of private gain and coordinated through the markets. Although there are good theoretical reasons for such an arrangement the theory is not easily transferred to the real world. Furthermore, when the essentially economic issues of social justice and ecological balance are considered, an economy based upon private decision making is sadly lacking (see pp. 6–10). Alternatively, economic activity can be generated and controlled by a single central decision-making body — the government. All decisions about demands, supplies, the use of resources and the behaviour of the individual elements may be contained in a centrally controlled economic plan and the government, whose interests in economic activity are less private than are those of the individual elements of an economy, may take decisions on an entirely different basis. More common than either of these two extremes is a mixture of decentralized and centralized (private and public) decision making in which the government can influence individual actions; act as a consumer, producer or resource owner; and can outline and implement a coordinated economic plan.

Measuring the flows around the economy

Just as the individual household or firm may record its receipts and expenditures, so too does the economy record its receipt of income and its expenditure upon goods and services. Because economies are most effectively cordoned along a national political boundary, where international economic transactions can be recorded with comparative ease, the most highly developed accounting systems are at a national scale. Regional accounts are sometimes constructed, but regions are far more open to outside influences than are nations and, in any case, do not usually have any effective measuring cordon around them.

One of the most fundamental measures of the size of a national economy is its gross national product (G.N.P.) defined as the total market value of finished goods and services produced by the nation over a year. Defined in this way G.N.P. is the sum of all spending by consumers, investors and government together with net exports — the difference between what is sold and bought abroad. G.N.P., however, can also be considered from the income or cost side which, because of the circular flow of money around the economy, must equal G.N.P. defined in terms of expenditure. In this second sense G.N.P. is the total cost of production and thus represents the sum of all wages, interest, profits, depreciation and sales taxes. G.N.P. minus all income from abroad is known as gross domestic product (G.D.P.). For comparative purposes it is sometimes appropriate to subtract depreciation from G.N.P., leaving net national product (N.N.P.), which is a measure of output excluding that for capital replacement. By subtracting sales tax from N.N.P. we are left with the value of the production of final, usable goods and services, known collectively as national income. By contrast the personal income received by individuals, involves certain additions and subtractions from national income. Thus profits retained by firms, taxes on company profits and compulsory social security payments must be subtracted, whilst interest on government loans and transfer payments must be added to national income in order to arrive at personal income. But, as is all too well-known, personal income does not become disposable income until income taxes have been paid.

The environmental relations of the economy

As pointed out on p. 4, the economy cannot exist in isolation, being but part of the total wider environment. We consider here some of the external social and ecological relations of the economy.

SOCIAL RELATIONS

It can legitimately be argued that a study of the economy as a mere generator of economic activity is both socially irrelevant and conceptually unsound since one of the major problems facing societies, at all levels, is the social implications of the concentration of economic power. This may be defined as the power of economies or their individual elements to influence, by unilateral action, the course of economic events in a lasting or substantive fashion. The international inequalities in economic development are very well-known, one implication being that less than 25% of the world’s population generates over 60% of its output (table 1.1). The remaining 75% of the population is, in consequence, placed at a considerable bargaining disadvantage in attempting to obtain a share of the world economy’s productive capacity and output commensurate with its needs. But some would go further than this and argue that the very process of development in one part of the world has the effect of impoverishing other parts because developed areas operate at higher levels of economic efficiency and so undercut less efficient producers. Furthermore, by offering higher remuneration, developed economies suck in resources from less-developed economies and so increase their own productive potential while decreasing the potential of the source areas. Without an efficient mechanism for redistributing such spatially concentrated wealth, major and increasing inequalities in social well-being develop. On the other hand, in the implementation (or perhaps more correctly imposition) of development programmes it is important not to transfer value systems from one situation to another. It is all too easy, for instance, to assume that the dream of each less-developed country is to become developed. Such a view can easily disregard highly developed local cultures. Self-respect is at least as important a measure of social and economic progress as are increases in urbanization, specialization, long-distance trading connections and material wealth (Adams 1970).

A non-spatial and more frequently publicised example of inequality in economic power is symbolized by the struggle for shares in the wealth created by capitalist production between, on the one hand, the owners and controllers of capital and firms and, on the other, the owners of labour resources. The inequalities in the economic power of these elements are related to the private ownership of capital and the ability of capitalist institutions to make resource-allocation decisions. Thus the distribution of income amongst resource owners, which is determined by the type, amount and firms’ evaluation of their resources and by the organized strength of their bargaining position, is an obvious symptom of their economic power and determinant of their social status and political influence. Clearly, as later chapters will show, the work situation is a fundamental social variable of much wider significance than in the mere production of goods.

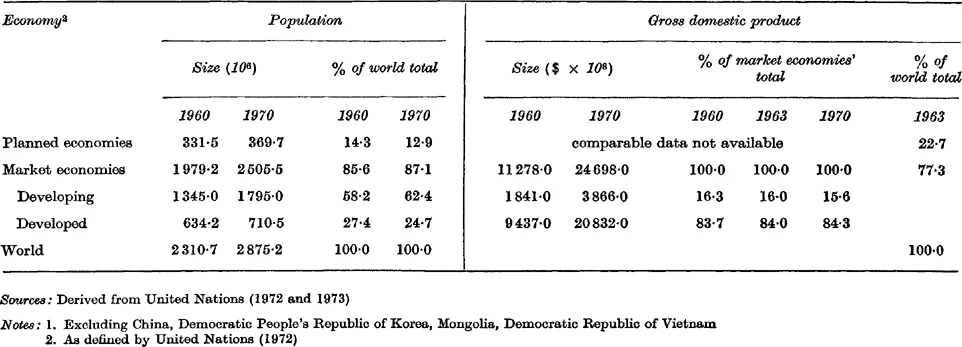

TABLE 1.1 World1 population and economic output 1960–70

ECOLOGICAL RELATIONS

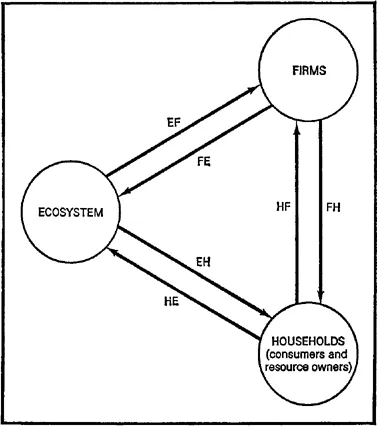

It has been frequently brought to public notice in recent years that economic activities are taking an increasing toll of balanced interactions within the life-giving ecosystem. The links between the economy and its ecologic environment are shown schematically in fig. 1.2. A circular, physical flow of materials can be traced out of the ecosystem through the economy and back into the ecosystem. This flow suggests that a crude policy of economic growth attacks the ecosystem in two ways: (i) by increasing flows of EF it depletes the natural resource base and feeds the flows of FE and HE which (ii) pollute the ecosystem with their waste and often toxic substances. It is now widely felt that the ability of the ecosystem to withstand this two-pronged attack is limited and that the effects of damaging withdrawals and additions are often intensified as they make themselves felt throughout the system as a whole.

1.2 The economy and the ecosystem. (Source: Coddington 1970.)

The demands made upon the ecosystem by the economy are increasing for two main reasons. First, the continued and increasing expansion of world population creates new demands upon the productive capabilities of economies and is partly responsible for the ever more widespread use of ecologically dangerous technology, especially chemical technology, in the short-term interest of increasing the output of goods. Secondly, the increasing standard of living of the members of advanced industrial economies results in an expanding range of sophisticated consumer tastes, especially for personal mobility which is threatening remote, ecologically fragile stretches of wilderness, congesting and polluting urban areas, and consuming vast quantities of non-renewable petroleum reserves. Increases in the flows within an economy automatically lead to increased demands upon the ecosystem, the cost of which can only be measured by the extension of conventional accounting systems adept at recording flows of HF and FH to include EF, FE, EH and HE (fig. 1.2).

The interaction of the economy with its higher order society and ecosystem illustrates the general problem posed by the boundaries and environment of a system under analysis: which elements are within the boundaries of the system, and which are in the environment and judged not to have any relevance for the analysis? While our emphasis in these pages is very much upon the economy per se, it is important to bear in mind the crucial links which exist between the economy, society and the ecosystem.

The spatial structure of the economy

A similar problem of delimitation faces the spatial analyst of the economy. Where does it end and where begin? Firms, for example, may sell goods to local, regional, national or international groups of consumers and may acquire resources, especially of capital equipment, from an equally wide distribution of resource owners. How can the economic geographer delimit the economy to which the firm belongs? The simple answer is that he cannot. The world economy may be considered closed, but any attempt to delimit a sub-world economy in either spatial or sectoral terms must accept that the economy, so defined, is more or less open to interaction with other spatial units or sectors. This point is taken up again later on when dealing with economic interaction in chapter 7.

The spatial structure of an economy consists of the two-dimensional spread of the aspatial, fu...