![]()

Part 1

A Russian Communist

Who I Am and What I Believe

This material was written and published between late 1993 and the presidential elections of June–July 1996. Included here are two major components: Zyuganov’s autobiographical sketch (1996) and fifteen topical commentaries compiled from different published sources, including an op-ed article from The New York Times. Together, these essays summarize Zyuganov’s “red-white” credo, which combines socialist ideas and Russian nationalism. According to Zyuganov, Russians have always associated socialism with traditional concepts of community that are deeply rooted in their unique national mentality.

—V.M.

About Myself

I am Russian by blood and spirit and love my Native Land.

I was born in 1944 in a place that has a special meaning for Russia. When a rooster crows in our village of Mymrino, he can be heard in three adjacent regions: our own Orel Region and the neighboring regions of Briansk and Kaluga. This juncture lies on the border of the steppe and the forest between the Oka and Volga Rivers, which is the birthplace of the Russian nation.

I come from a family that has produced three generations of teachers. Although some family members were and others were not communists, they all shared these two characteristics: working hard from morning until evening and, almost without exception, fighting for their country. Many did not return from the last big war. My father, Andrei, lost his leg in the battle for Sevastopol.

I had my first job while still in high school, and, after graduating with distinction, I worked for a year in my school as a teaching assistant. Then my village collective sent me to a teacher’s college in Orel. I consider teaching to be a profession worthy of respect and esteem. In my family virtually everyone teaches, either in school or at the college level. Together, we could educate a young person under one roof, so to speak. Among us are mathematicians, physicists, literary scholars, and historians. By the way, my own first teacher was my mother, Marfa, who taught elementary school for forty years. I remember that in my four years as her pupil I only once called her “mother” in class; she was strict and demanding.

During my sophomore year in college, I was drafted into the army. I served in a radiation and biochemical reconnaissance unit (in East Germany), which was not something to be envied. Of my three years of military service, one year was spent wearing a gas mask and a protective rubber suit; I burned three pairs of boots saturated with radiation.

In 1966, while serving in the army, I joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), believing that the communist idea, which is over two thousand years old, most profoundly expresses people’s needs and hopes. It is in accord with the Russian traditions of communality and collectivism, which meet the fundamental interests of my country.

Upon being discharged from the military, I completed my studies in physics and mathematics at Orel Teacher’s College, went on to do graduate work at the Academy of Social Sciences in Moscow, and defended my dissertation in philosophy. This enabled me later to teach higher mathematics and philosophy at the college level.

I have been married to my wife, Nadezhda, for over thirty years. We have two grown-up children—a son, Andrei, and a daughter, Tatiana—both of whom are married and are pursuing their professional careers. We have two grandsons, Leonid and Mikhail. At this time, three generations of our family, including my widowed mother, our daughter, and her husband, share one apartment in Moscow.

As for my career in the Party apparatus, I tried my hand at virtually every single rung of the CPSU Central Committee on Old Square in Moscow. As part of my duties there, I traveled extensively over the entire country, from its western borders to Sakhalin Island and from the Baltic Sea to Central Asia. During my last ten years at the Central Committee, as one of the handful of party officials assigned to the special “War Contingency File,” I personally investigated every social upheaval in the country, thus gaining first-hand experience in dealing with emerging major problems.

In my capacity as a deputy chief of the CPSU Ideological Department working on Russian problems, I actively supported the idea of creating a separate Russian Communist Party as a party that would protect Russia’s national state interests within the CPSU. This idea was opposed by Mikhail Gorbachev and his crew, who at that time, rather than debate our arguments, mounted a vicious propaganda campaign trying to discredit me and other Russian communist leaders.1

I have much to repent. First of all, I blame myself for not finding the time and the opportunity to expose fully the mafia-like political structure of the CPSU, at the very top level of which I worked. I have much to repent because already in the late 1980s my colleagues and I working on Central Asia had evidence that a blood bath, which could have cost some 100,000 lives, was in the making in Tajikistan.2 By the same token, my colleagues and I who were involved with the Caucasus warned the Georgian leadership and others that if their unchecked rush for sovereignty were to spill over the borders, they would face the same situation that had existed some two hundred years earlier, before the treaty that voluntarily joined the area with Russia.3 I also worked on the issue of rising crime in the country, unsuccessfully trying to put it on the agenda of the Politburo. The top political leaders likewise preferred not to deal with problems in the Armed Forces and with the situation in the Baltics. All warning signals, like mine, were swept under the rug and ignored.

As a communist who joined the Party for ideological reasons, I wholeheartedly welcomed perestroika and did my best to expedite its advent. The Soviet model of socialism was in urgent need of a qualitative change. But during the past decade our country has been twice deceived and betrayed: first by Mikhail Gorbachev and his immediate cohorts, who, while promising needed reforms, destroyed the Soviet Union and all its structures; and then by Boris Yeltsin, who finished the job under the cover of idle talk about “democracy” and a “market economy.”

It was against this tragic background that I became one of the leaders of the opposition. Early in 1996,1 accepted the nomination to run for the presidency of Russia as the candidate of the National Patriotic coalition, which includes the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF). Unfortunately, I did not win, although approximately 30 million people—more than 40 percent of those who voted—cast their ballots for me.

At present, I serve concurrently as chairman of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation and of the National Patriotic Union “Russia,” which is the new name of our united opposition movement. I am also the leader of the CPRF faction in the State Duma.

About Socialism

The entire history of humankind in the twentieth century demonstrates that we should move forward to socialism. And in doing so, we should not discard the positive experience of the past but rather thoroughly analyze it and adopt what was good in it.

The goal of a society of social fairness emerged long before Marxism, and the realization of that ideal has enlisted followers of different ideologies, from Christian socialists to anarchists. The socialism that was built in the USSR and a number of other countries was, of course, far from perfect. But it exhibited some historic achievements. The socialist system enabled us to create a powerful state with a developed national economy. We were the first to venture into the cosmos. Our culture reached unprecedented heights. We were justly proud of our achievements in science, theater, film, education, music, ballet, literature, and the visual arts. Much was done to develop physical culture, sports, and folk arts. Every citizen of the USSR had the right to work, free education and medical care, and a secure childhood and old age. Appropriate budgetary allocations subsidized housing and provided for the needs of children. People were sure of their tomorrow. A workable alternative to capitalism was created in our own country and in other socialist countries. This was the concrete historical justification of the socialist path of development.

Not even our ideological opponents can understand why we ourselves destroyed that which in many ways was working so well. Today we are calling for a renovated socialism free of deformities and fatal errors and mindful of everything modern and progressive that humankind has created.

Why Did Soviet Socialism Fail?

I believe that our people have never rejected socialism. They were simply deceived by demagoguery and false promises. Remember Gorbachev’s and Yakovlev’s vocabulary during the past ten years?4 They used to say “More democracy—more socialism,” “For socialism with a human, democratic face,” “Perestroika is continuing what was started by the Great October Revolution,” “Reforms are taking Russia’s socialism to the level of modern civilization,” and so forth. Everything that was being done in the name of these and similar slogans was taken by the people at large to mean not the destruction but the improvement of socialism. After all, these slogans were proclaimed by persons commanding the respect of the Party and the nation. They were the highest-ranking leaders in the country, whose honesty was taken for granted.

A majority of the people, under the stress of events, mistook populist demagoguery for the expression of national consensus. By the mid-1980s, there was much disappointment with the slow economic development and the stiffening bureaucratization of the Party and the state administration. Millions of citizens felt alienated from state affairs because the Party monopolized power and minimized the role of the soviets [elected councils].

It is clear now that a decisive role in the destruction of the country was played by a subjective factor—the weakness and incompetence of the leaders then in power. Those people displayed personal cowardice, which later turned them into traitors and led to a degeneration of a part of the ruling elite.

On active military duty in East Germany.

Zyuganov (left) with his graduating class.

In younger days.

A visit to Red Square. From left: uncle, father, son Andrei, mother, Zyuganov (man at right unidentified).

Dancing with daughter Tatiana.

At the summer house.

Zyuganov helping his daughter and his mother at the kitchen table.

A picnic.

With daughter Tatiana, wife Nadezhda, and cat (Basil).

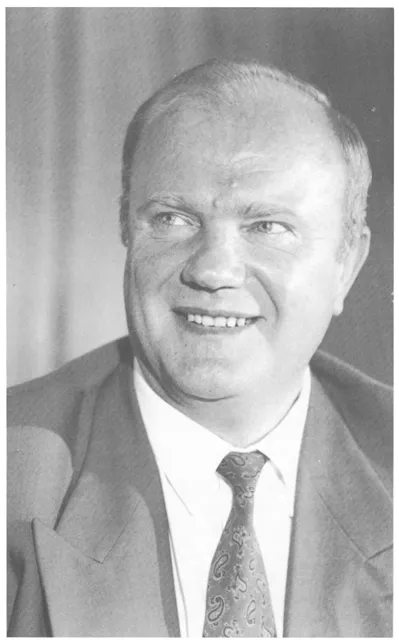

The candidate.

It is widely agreed that the crisis, caused by a power struggle at the top, was cleverly used by foreign intelligence services and centers of ideological warfare.

Objective reasons contributed to the defeat of socialism. Socialism had failed to realize its full potential in such important areas as labor productivity, the well-being of average workers, and the involvement of broad masses of the people in the creative process. Russia had been drawn into an exhausting arms race, and, in trying to catch up economically with the West, we fell into imitating Western values and observing Western priorities.

On Reforms

The radical reforms started in January 19925 have brought catastrophic results. Today it is clear that the real goal of the “reformers” was the destruction of Russia’s economy under the slogan “The state must be removed from managing the national economy.” The country has been deeply damaged by th...