![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

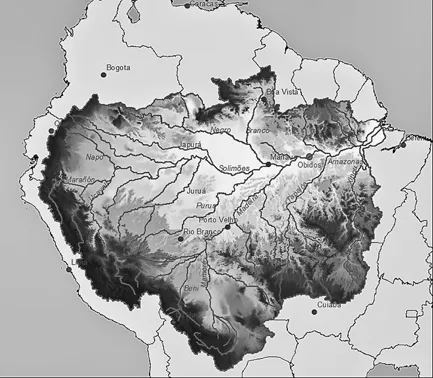

The Amazon basin is a jewel of the natural world. It is the largest drainage basin on Earth, occupying an area estimated to be 6,869,000 square kilometers or roughly 40 percent of the South American continent (see Figure 1.1). It encompasses parts of the territories of nine countries: Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guyana (France), Guyana, Peru, Surinam, and Venezuela. However, 69 percent of it is situated in Brazil. The basin is teeming with life. It is one of the most biodiverse systems in the world. Most of it, an estimated 5,500,000 square kilometers, is occupied by dense tropical forests; this represents 56 percent of all broad leaf forests in the world (GIWA 2004; McAllister 2008; Organization of American States 2005). It contains more than 30,000 species of plants, nearly 2,000 species of fish, 60 species of reptiles, 35 mammal families, and approximately 1,800 bird species (Organization of American States 2005: 2; see also Vadjunec, Schmink, and Greiner 2011: 2–3).

Amazonia is a vital system for climate stability. Its forests retain an immense amount of carbon that, if released, would greatly contribute to climate change. The basin contributes to the Earth’s cloud convection systems, leading some to refer to the clouds it generates as “floating rivers.” These take water to the rest of Brazil and other South American countries (see “Correntes de ar da Amazônia levam chuvas ao sul e sudeste do Brasil” 2009; “‘Rios voadores’ da Amazônia transportam água para Brasil e América do Sul” 2012). Unfortunately, in Brazil alone a cumulative area of 757,661.54 square kilometers of Amazon rainforest had been deforested through 2012, representing 18.6 percent of the Brazilian portion.1 The non-governmental organization (NGO) Mongabay provides an estimate of the combined cumulative deforestation for Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guyana (France), Guyana, Peru, Surinam, and Venezuela of 541,932 square kilometers through 2012 (www.Mongabay.com 2013). This leads to a cumulative deforestation estimate for the forest as a whole of roughly 1,299,593.54 square kilometers through that year—an area about 14 percent bigger than the whole of Colombia, whose area is 1,142,000 square kilometers. Brazil deforested another 5,891 square kilometers of Amazon forest in 2013, and an additional 4,848 square kilometers in 2014 (Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais—INPE n.d.a).

The Amazon rainforest creates a dilemma for Brazil—and for all Amazonian countries for that matter. On one hand, it signifies a reservoir of resources and a

Figure 1.1 The Amazon river basin

frontier of economic development in a country that is rising in the world economy; on the other hand, it is recognized by scientists, environmentalists, and the general public as a vital ecosystem that must be preserved. This dilemma manifests itself in the ecopolitics of the region, with different political blocs fighting for their respective visions for the future of the forest, both in Brazil and abroad. In the words of Brazilian scholar José Augusto Pádua, Amazonia is an “ideological forest” (floresta ideológica; in E. Guimarães Neto 2008); that is, it has political meaning that transcends its physical characteristics. One political bloc argues that developing the region is imperative for the future of Brazil: for example, developmentalists argue that Brazil’s energy needs require the construction of hydroelectric dams in the region and that expansion of economic activities and colonization farther into Amazonia will contribute to economic growth. This political bloc includes agents such as big business, farmers, politicians, and other proponents of development who view Amazonia as a place of economic potential, a place with vital natural resources to fuel Brazil’s development. It tends to attract conservative nationalists who argue that Brazil must develop Amazonia before other countries invade it and take control of its vast natural resources. This nationalistic stance against the possibility of foreign imperialism has certainly been openly espoused by important members of the Brazilian armed forces. For them, what Brazil does to its forest is nobody’s business but Brazilians’. In opposition to this is the political bloc that is critical of the current system of development and fights to protect Amazonia. This bloc includes scientists, environmentalists and their organizations, and others who see the intrinsic importance of Amazonia as an ecosystem: for example, for climate stability and for biodiversity. Some environmental organizations, such as Greenpeace and the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), have even proposed “zero deforestation” in the region. This bloc also includes indigenous people and “extractivists,” such as rubber tappers and Brazil nut gatherers. For these latter groups, the forest is home and it sustains their livelihoods and cultures. A third political bloc is composed of those individuals who favor “sustainable development,” which loosely means development that “respects the environment” and satisfies the environmental needs of the current and future generations. This concept appeals to people and organizations of different political persuasions. For instance, it has been embraced by several NGOs, and by some farmers who believe “high-input, high-output agriculture is compatible with environmental goals and means” (Brannstrom 2011: 540). This has become a sort of “official rhetoric” of the Brazilian government in the last three decades. Although quite appealing to those who believe that development and environmental protection can occur simultaneously, sustainable development is viewed as an oxymoron by critics; for them, development under capitalism is associated with economic growth, which, in turn, leads inevitably to exploitation of natural resources (see Redclift 2006).

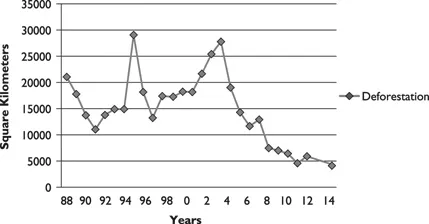

While this book pays close attention to these different sides of the conflict over Amazonia, its main focus is documenting the strengths and limitations of the environmental movement in creating positive change towards protection of the forest. It shows how the movement to save Amazonia has been a strong and often decisive force in the Brazilian politics of development versus preservation. Environmental, grassroots, and indigenous organizations have fought fiercely against destructive plans for economic development of the region, often facing intense hostility from opposing forces, including violence and assassinations. Some of these organizations, such as Greenpeace, have become guardians of Amazonia, working diligently to stop deforestation. Their efforts have contributed to Brazil taking significant steps towards environmental preservation since the mid-1980s. From the ecopolitics of “Amazonia is ours to do as we please” of years past (see L. Barbosa 2000), a significant portion of Amazonia (43.9 percent in 2010) is currently under some form of legal protection, with conservation units accounting for 1,110,652 square kilometers (22.2 percent) and Indian reservations for 1,086,950 square kilometers (21.7 percent) in that year (Veríssimo et al. 2011: 15–16). After an increase of 28.88 percent from 2012 to 2013 (see Figure 1.2), the yearly rate of deforestation declined by 17.71 percent between 2013 and 2014, to 4,848 square kilometers. Recent rates of deforestation remain at their lowest levels since 1988.

Figure 1.2 Annual deforestation rate for Brazilian Amazonia, 1988–2014

The political activism of groups trying to save Amazonia has contributed to the general public’s awareness of this issue in Brazil. It has also pushed corporations and the Brazilian government to engage in efforts to improve their environmental record in the region. However, I do not wish to paint a rosy picture of the situation. Much remains to be done to save the forest. First, over 50 percent of Amazonia lies outside Brazilian conservation units or Indian reservations, which makes this portion of the forest more susceptible to invasion and deforestation. In addition, conservation units and Indian reservations themselves are not immune to deforestation. It has been estimated that 25,730 square kilometers of forest had been cleared in these areas by 2009—13,249 square kilometers in conservation units and 12,481 square kilometers in Indian reservations (Veríssimo et al. 2011: 63). This represents 3.5 percent of all the deforestation that took place in the region up to that year.2 According to a 2013 report of an audit conducted by the Tribunal de Contas da União (Tribunal of the [Federal] Union’s Accounting), only 4 percent of 247 state and federal conservation units in existence in Amazonia met adequate operational requirements, such as enough personnel; and only 40 percent of them even had a management plan to guide their activities (Tribunal de Contas da União 2013).

Despite the above-listed limitations, the passage of environmental legislation, moratorium agreements, campaigns to modify, stall, or prevent environmentally harmful projects, the creation of Indian reservations and natural reserves, and recent declines in rates of deforestation all attest to the involvement of environmental organizations and their efficacy in generating change for the better. These accomplishments have been achieved against great odds. The history of environmentalism in Brazil is one of opposition to powerful forces pushing the frontier of capitalism farther into the forest. It is a history of battles against powerful economic interests as well as environmentally unsound government plans, which are often disguised in nationalistic rhetoric, thus making attacking them seem unpatriotic. It is also a history of fighting against illegal activity and/or corruption. This can sometimes make environmentalism in Brazil a very hazardous activity.

A major theme in this book is the politicization of commodity chains as a weapon in the preservation of Brazilian Amazonia. A commodity chain “is a network of labor and production processes whose end result is a finished commodity” (Hopkins and Wallerstein 1994: 17). It connects production units, such as cotton farms, at one end of the chain to buyers or consumers at the other through a series of “boxes” or “nodes,” where different aspects of production are performed. These boxes or nodes might be located in different geographic locations throughout the world. As is shown in this book, environmental organizations have politicized several of the commodity chains linking Amazonia to various regions of the world and have turned them into political weapons against deforestation. They have used knowledge of these commodity chains to press corporations and the Brazilian government to change course. I view this as part of a movement to politicize consumption globally. Environmental organizations have especially used Amazonia’s economic links with environmentally sensitive markets such as the European Union (EU) to their advantage. I explain some of the main conflicts involved in this strategy and how they have shaped policy for Amazonia.

Any serious discussion of current environmental issues in Amazonia has to address important aspects of globalization, such as global commodity chains. In addition, it has to be informed by what I call the duality of globalization. Globalization has brought new dimensions to struggles over Amazonia. It has been a double-edged sword in the fight for preservation of the forest. On one hand, it has maximized the political strength of the organizations fighting for preservation by linking them to larger, international networks of environmental organizations. Several of the major international environmental organizations have opened offices in Brazil, including Amigos da Terra–Amazônia (Friends of the Earth–Amazonia), Greenpeace Brasil, and WWF Brasil; and several national and local organizations receive foreign financial support. In addition, links to international organizations have helped bring Amazonian issues to the attention of the international public. On the other hand, globalization has opened up new market opportunities for Brazil—including the vast Chinese market for products such as soybeans and minerals—and, thus, has become a major force behind the growth of economic activity in Amazonia, such as the expansion of agriculture, cattle ranching, and mining. Amazonia has become connected to distant markets via global commodity chains (explained in more detail below). Even though the relationship between economic expansion and deforestation for some sectors of the Amazonian economy seems to be “decoupling” in recent years (see Chapter 4), what happens in distant markets continues to shape environmental politics in the region.

In sum, globalization has established new economic links or commodity chains between Amazonia and the outside world, and powerful economic interests have tried to expand these. However, globalization has also strengthened the movement to save the forest. This movement has politicized commodity chains linked to the region in its attempts to stop deforestation. It has used this as a strategy that threatens the profits that corporations can make by operating in Amazonia.

Theoretical backbone

This book employs theoretical ideas as heuristic devices3 or tools for the understanding of particular situations in Amazonia. This should be made clear due to the ideological controversies in the social sciences concerning theory and theoretical applications (see L. Barbosa 2014). I do not use Amazonia in this book as a case study to “test theory” in the strictest sense of scientific methodology. Theory, in this book, is used as a tool or a guide to aid understanding of empirical or historical situations. It places the occurrences described in these narratives within a larger context of global capitalism in order to show that what has taken place in Amazonia is part of a bigger issue affecting the remaining tropical forests of the world and other ecosystems.

The history of Amazonia is one of capitalism’s frontier expansion into the region. I feel that world-system theory offers the best set of tools or concepts for the understanding of this process, including tools such as commodification, commodity chains, incorporation, antisystemic movement, and so on (see below). However, I also use theoretical insights from other approaches when discussing the dynamics of NGO alliances, campaigns, and networks. Due to its macro level of analysis, world-system theory does not provide the meso and/or micro-level focus that is sometimes required to understand better the dynamics of these associations: for example, the roles individuals play, the importance of technology, and so on (Smith and Wiest 2012: 35). I begin with an overview of world-system theory.

An overview of world-system theory

According to the sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein, a main proponent of world-system theory, the modern capitalist world economy has its roots in the “long sixteenth century,” a period of time from 1450 to 1640 when the European capitalist economy began to expand and engulf other parts of the world via colonialism (Wallerstein 1974a; 1974b). The result has been a global stratification system with a clearly established division of labor. Colonial expansion made the Western European countries the “core” of the world economy and the newly incorporated colonial areas the “periphery.” In the first half of the twentieth century, the United States joined the core of this economy; Japan joined in the second half. The relationship between core and periphery has been one of economic exploitation and political domination. The periphery provides agricultural goods, raw materials, and cheap labor to the core; peripheral countries also depend on the markets of the core for their products. In between the core and the periphery lies the “semiperiphery,” a category of great importance for the arguments in this book. Like the core, the semiperiphery is small. It is comprised of former core countries that have declined and those few peripheral countries that have managed to climb out of poverty, such as South Korea in the latter part of the twentieth century. How world-system scholars conceive the core and periphery dimensions impact how they view the semiperiphery. Some think of the semiperiphery as exhibiting half core-like and half peripheral-like attributes, while others view at least some semiperipheral areas as engaged in qualitatively different activities (Shannon 1996: 28–29).4

Some special considerations about the semiperiphery

One important feature of semiperipheries is how they attempt to free themselves from core dominance. This often manifests itself in political assertiveness in international situations. Aware of their economic power, the governments of these countries resent attempts at manipulation. When intimidated, they demand international recognition and respect. Countries such as China and Russia frequently flex their political and military muscles in international disputes, to show that they are not poor peripheral countries that can be easily pushed around. Brazil is no exception to this. It has in recent years taken political stances on international issues that seemed confrontational in relation to core countries. For example, former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003–2010) frequently and publicly blamed the developed countries for many of the world’s problems, such as climate change and poverty in the developing world. He also pushed Brazil (along with Turkey) into a failed attempt to broker an agreement with Iran to limit that country’s use of nuclear energy, a maneuver that irritated the US government (Gamboa 2010). Brazil has also announced its goal of becoming a permanent member of the UN Security Council, thus challenging the current arrangement (which is dominated by core countries). Attempting to achieve international recognition has also meant adjusting policies and engaging in collaboration. For example, while belligerence against international criticism about the destruction of the Amazon rainforest was the norm up to the late 1980s, the tone became more conciliatory in the early 1990s. A desire to see their country recognized internationally led presidents such as Fernando Collor de Mello, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to take import...